lawrence underground railroad driving tour

Use this arrow to learn more at each stop.

This tour was underwritten by the Institute of Museum & Library Services.

Mural in Torrington, Connecticut depicting abolitionist John Brown leading eleven Missouri freedom seekers and a newborn baby to the Grover Barn Underground Railroad Station in January 1859. Artist: Arthur Covey.

The Underground Railroad (UGRR) was a highly secretive network of routes and safe houses operated by abolitionists who helped enslaved people seek freedom in the northern US, Canada, or Mexico. Many enslaved Blacks took the first step toward emancipation by running away from their slaveholders and joining this network. White, Black, and Native American “conductors” helped transport the freedom seekers as “passengers” to different “stations,” while “station masters” offered them shelter in their houses or barns. For these reasons, the Underground Railroad has been called the first Civil Rights movement.

But the Underground Railroad was risky for both the freedom seekers and those assisting them, so secrecy was crucial to protect everyone involved. Anyone who assisted the freedom seekers in gaining their freedom defied the US Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. They risked being jailed for six months and fined $1,000 for each offense.

It is estimated that between 300 to 1,000 freedom seekers passed through Douglas County, Kansas Territory, on the Underground Railroad between 1855 and 1861. Although their exact numbers are unknown, we now know some of their names, as discovered in diaries, letters, and newspapers. Some UGRR stories in Lawrence have been documented and handed down through the generations. These stories provide a rich heritage and offer a glimpse of a mostly unwritten history.

It is estimated that between 300 to 1,000 freedom seekers passed through Douglas County, Kansas Territory, on the Underground Railroad between 1855 and 1861. Although their exact numbers are unknown, we now know some of their names, as discovered in diaries, letters, and newspapers. Some UGRR stories in Lawrence have been documented and handed down through the generations. These stories provide a rich heritage and offer a glimpse of a mostly unwritten history.

Scroll down to begin the tour.

Stop 1

Lawrence Ferry Crossing – Ike Gaines UGRR Site

195 - Locust at 2nd, Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSLawrence Ferry Crossing – Ike Gaines UGRR Site

195 - Locust at 2nd, Lawrence, KS

Drive to the north side of the Kansas River and park in the lot east of N. 2nd St. off Elm Street near the levee. Imagine what a freedom seeker must have felt as he or she looked across the river to Lawrence which represented freedom to runaway slaves.

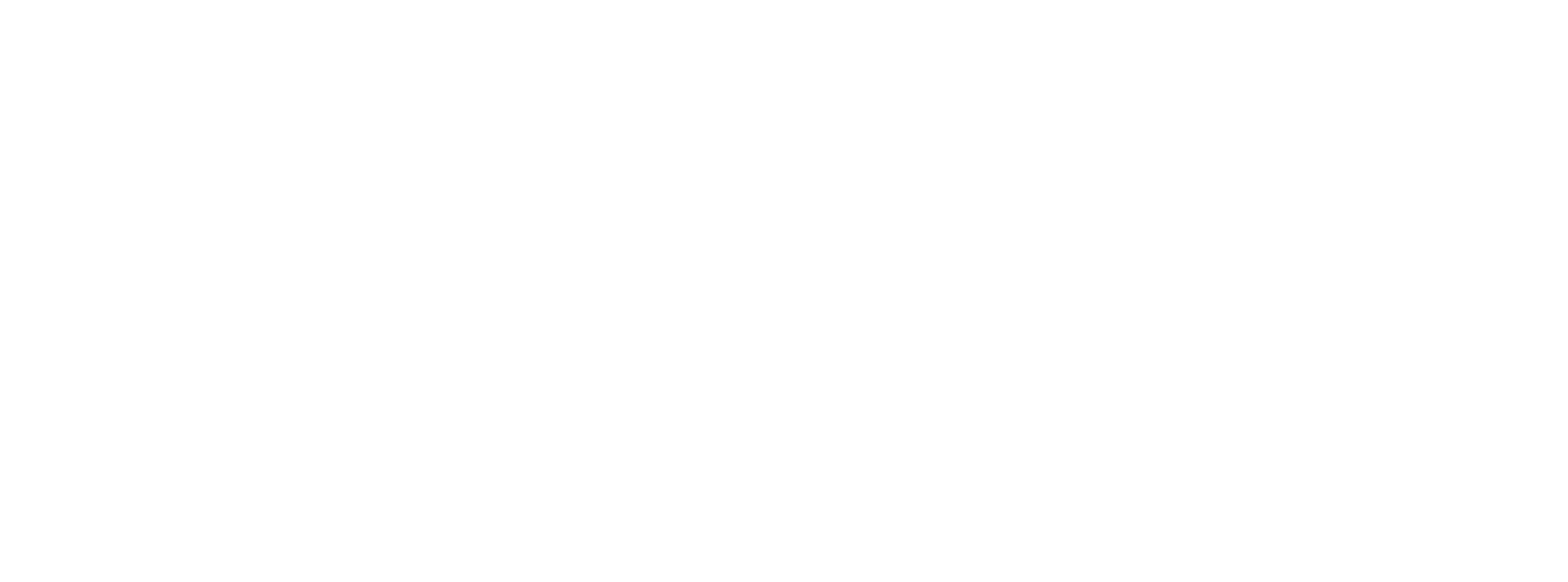

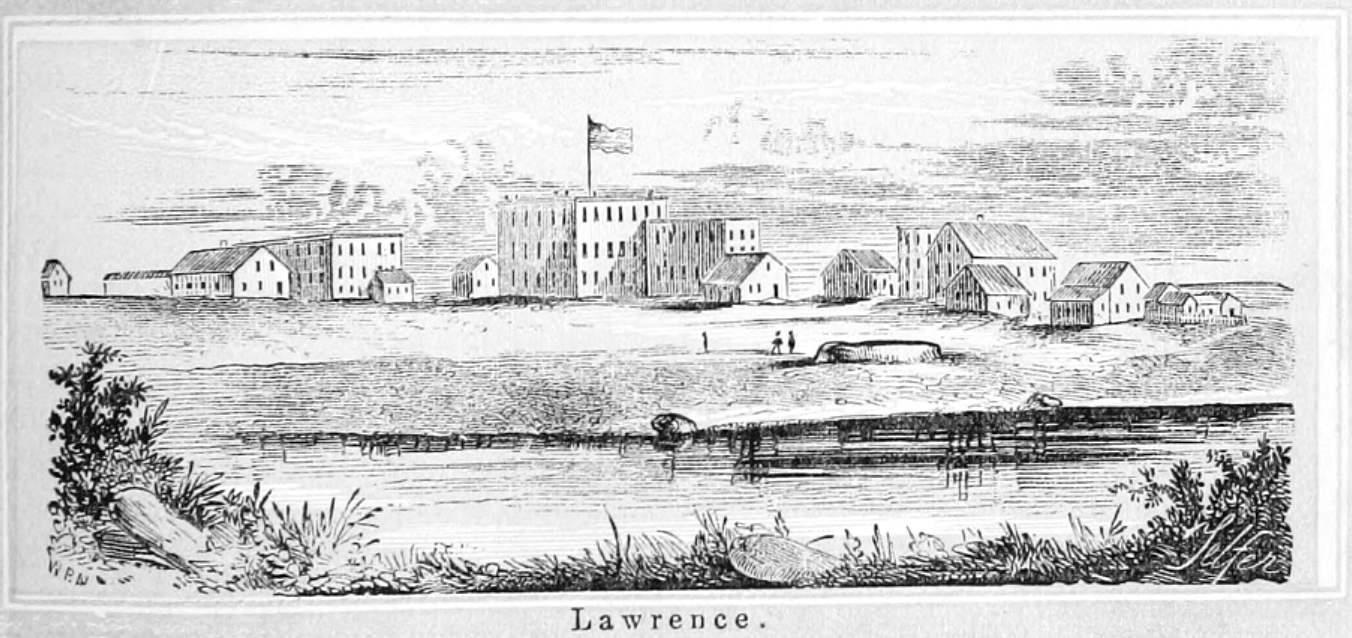

Illustration of the ferry crossing the Kansas River from the Delaware Reserve (now North Lawrence) to the south bank of Lawrence. The Free State Hotel and Mount Oread can be seen in the distance. In Beyond the Mississippi, by Albert Richardson, 1857.

About 1860, a young but weary fugitive slave, Ike Gaines, from Platte City, Missouri appeared on the north side of the Kansas River near the Delaware Reserve and cautiously approached a white man, Jake Herd, who was working on a boat near the ferry. He whispered to Herd:

“Excuse me, Sir. How do I get to Mr. Jim Lane’s house?”

Herd sent him across the river on the ferry to a landing located at the base of New Hampshire Street. Mr. Gaines told two men on the other side that he wanted to see Mr. Jim Lane because he had heard that Lane was known to help freedom seekers. The men replied,

“We’ll take you to Jim Lane’s house.

Certainly, we will. Come along!”

“Excuse me, Sir. How do I get to Mr. Jim Lane’s house?”

Herd sent him across the river on the ferry to a landing located at the base of New Hampshire Street. Mr. Gaines told two men on the other side that he wanted to see Mr. Jim Lane because he had heard that Lane was known to help freedom seekers. The men replied,

“We’ll take you to Jim Lane’s house.

Certainly, we will. Come along!”

The men were William Clarke Quantrill [using the alias “Charlie Hart”] and Frank Baldwin, both “slave stealers.” Mr. Gaines conversed freely with them, told them his name, and that he had run away from the plantation of Joanna Gaines, a widow in Platte City, Missouri.

But Ike Gaines never got to the house of Jim Lane. Instead, he was bound by the two men, tied to a horse, and taken to Jake McGee’s house a couple of miles up the river. Later that night, Jake McGee, “Charlie Hart,” and Frank Baldwin took him to Westport, Missouri. After the trio negotiated with Mrs. Gaines, Ike Gaines was returned to her where he faced a lifetime of slavery after getting so close to freedom. He wasn’t the only victim, because these men also extorted $500 from Mrs. Gaines instead of the usual $200 normally paid for the reward.

Stop 2

Monteith UGRR Station

645 Vermont St. Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSMonteith UGRR Station

645 Vermont St. Lawrence, KS

Drive across the bridge straight onto Vermont Street and park on the right side near the post office to imagine the Monteith home near the old ravine (now Watson Park).

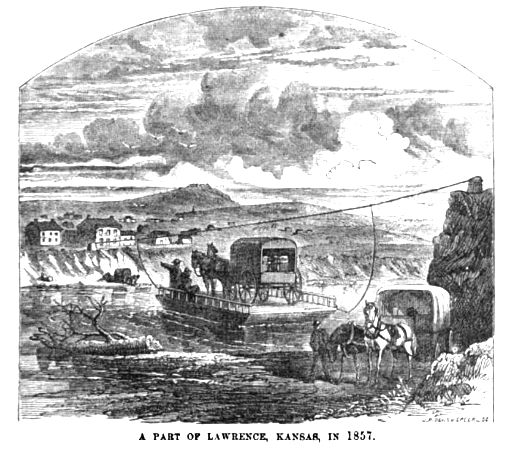

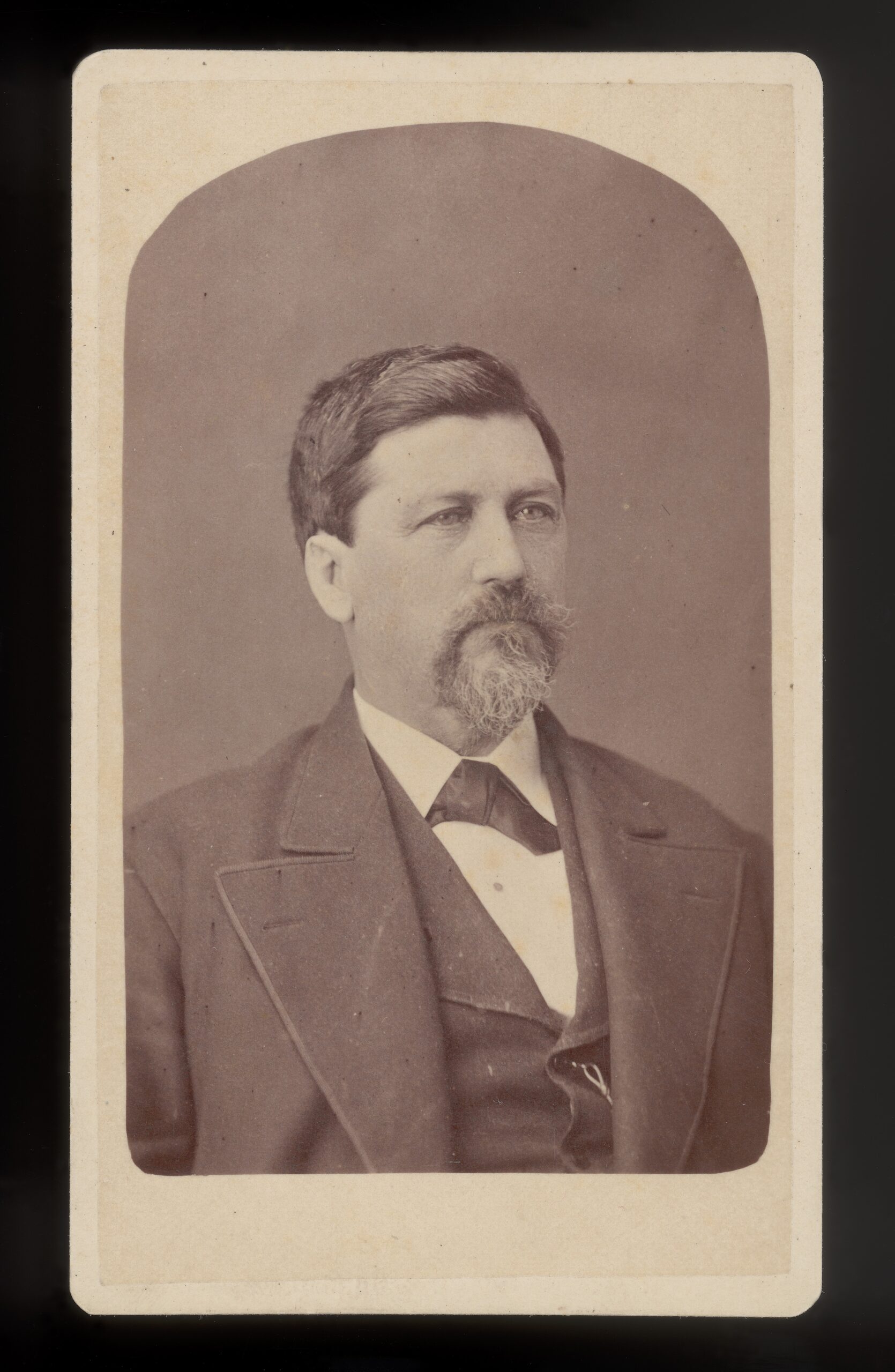

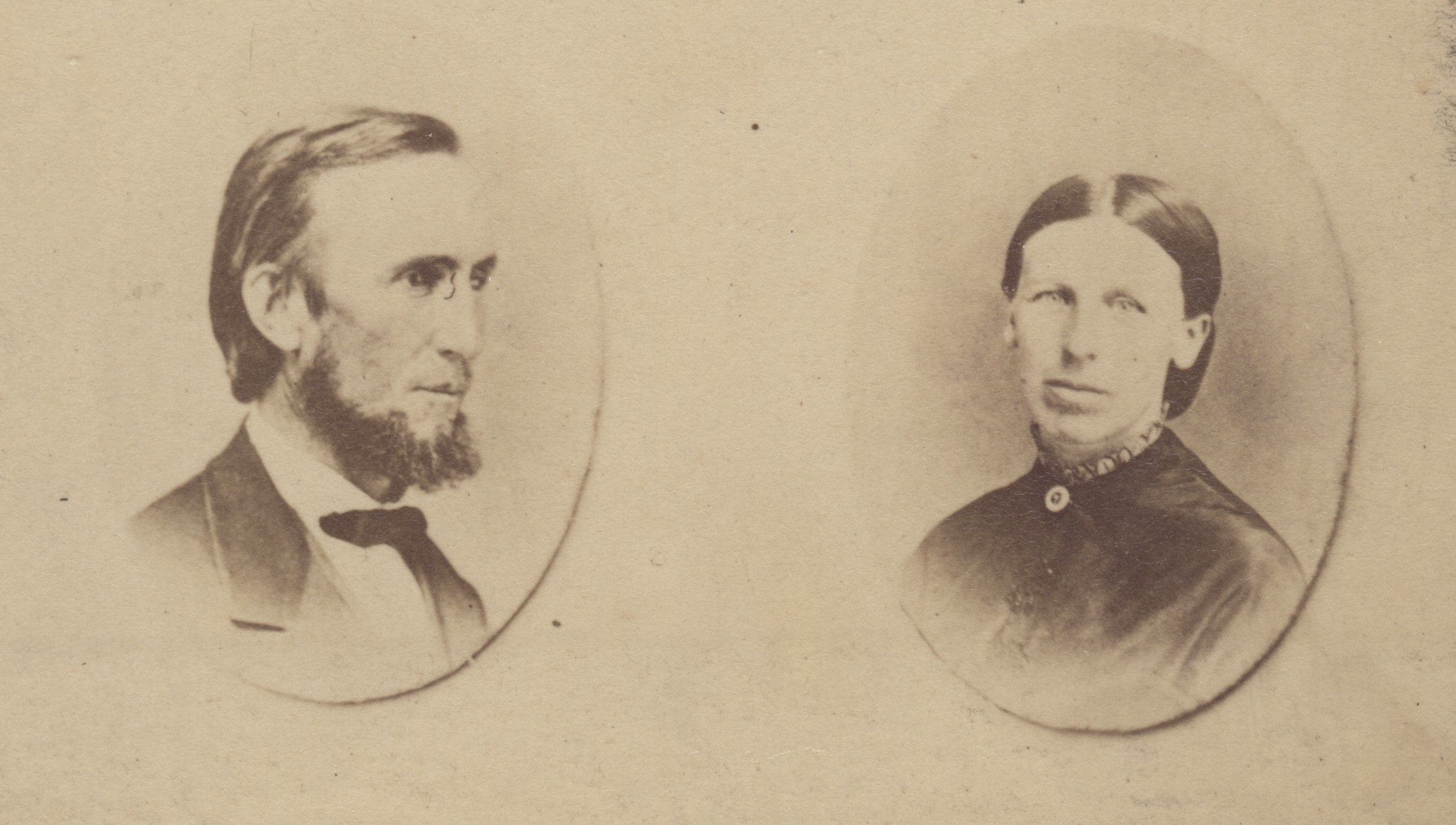

Detail of Photograph of William R. Monteith ca. 1860.Courtesy of A. V. Wuelfing. In the 1850s William Monteith and his wife, Isabella (Gilchrest) Monteith moved from McIndoe Falls, Vermont to Lawrence, Kansas Territory, where they "extended help to many a poor fugitive from bondage."

By the fall of 1859, the Monteith family moved from their property (about 4 miles south of Lawrence) into town and lived on the north end of Vermont Street. Lizzie stayed with them for a while until she was moved to the next UGRR station.

In February 1860, a Lawrence newspaper reported that a gang of pro-slavery men had gone to the Monteith home one night that week at about 11 p.m. They tried to break into the house to kidnap a young unnamed “colored woman” sheltered there.

The notorious slave-catcher, Jake Herd, along with Mr. Roberts, and Jim Lester, knew that Mr. Monteith was not at home. A boarder in the house, Mr. Bigelow, became alarmed at the intruders and grabbed a piece of wood to defend himself.

In February 1860, a Lawrence newspaper reported that a gang of pro-slavery men had gone to the Monteith home one night that week at about 11 p.m. They tried to break into the house to kidnap a young unnamed “colored woman” sheltered there.

The notorious slave-catcher, Jake Herd, along with Mr. Roberts, and Jim Lester, knew that Mr. Monteith was not at home. A boarder in the house, Mr. Bigelow, became alarmed at the intruders and grabbed a piece of wood to defend himself.

A child in the house alerted the neighbors of the attack, and one of them shot at Mr. Roberts as he headed for the nearby ravine. Roberts was then taken to the river but later released and told to leave town.

A group of Black people knocked Roberts off his horse and punched him. Meanwhile, Jake Hurd had already fled the scene. Luckily, with the combined counterattack on the slave catchers by Monteith’s border, neighbors, and a group of Blacks, the slave catchers were sent running, and this woman was not kidnapped nor returned to a life of slavery.

A group of Black people knocked Roberts off his horse and punched him. Meanwhile, Jake Hurd had already fled the scene. Luckily, with the combined counterattack on the slave catchers by Monteith’s border, neighbors, and a group of Blacks, the slave catchers were sent running, and this woman was not kidnapped nor returned to a life of slavery.

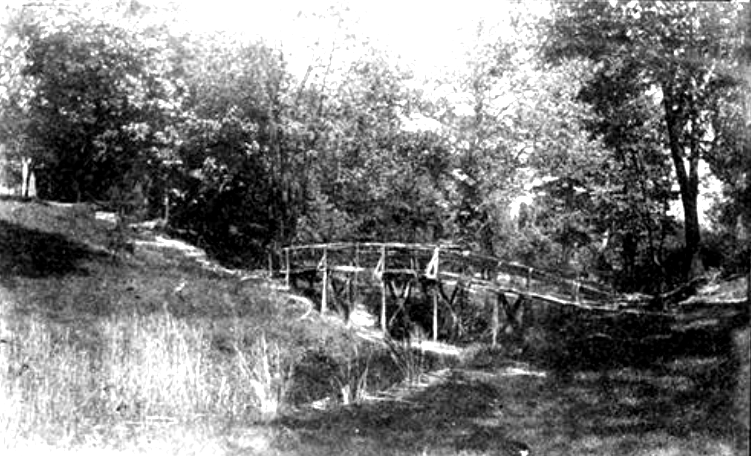

Photograph of the ravine (now Watson Park) where Monteith’s home was located on Vermont Street and where refugees hid during Quantrill’s raid on August 21, 1863. A foot bridge, located near the current basketball courts, allowed people to access their west side homes from downtown.

Stop 3

Wood UGRR Station

705 Massachusetts St. Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSWood UGRR Station

705 Massachusetts St. Lawrence, KS

Try to find a parking space between the Eldridge Hotel and 715 Restaurant to imagine the Woods’ cabin.

Photo of Samuel N. Wood, [n.d.] by Leonard and Martin. KansasMemory.org, item 90676

Photo of Mrs. Margaret Walker (Lyon) Wood, Wikitree

View of downtown Lawrence in early 1855. The Free State Hotel is the tall building with the flag. The Wood cabin is the small building located two doors to the left (south of) the hotel. From Historical Collections of the Great West, Henry Howe, 1855

A Lawrence newspaper documented one of the first UGRR stories in the spring of 1855 that concerned “Lizzie," an enslaved woman about 22 years old who came from the Marais des Cygnes area of southern Kansas. Lizzie had run away from her slaveholder, Mr. Yocum/Yokum, and contacted Tauy Jones, a Native American living near present-day Ottawa, Kansas. His neighbors, William Partridge and Partridge’s sister, volunteered to take her to Lawrence.

Here, Lizzie was sheltered for a few days in the home of white abolitionists, Sam and Margaret (Lyon) Wood. Their frame shake cabin, one of the first built in Lawrence, was located on Massachusetts Street, two doors south of the Free State Hotel, partially on the vacant lot near where the current Eldridge Hotel stands today and partially on the lot of present-day 715 Massachusetts. (Both the cabin and the Free State Hotel were later burned during the Sack of Lawrence in 1856.)

Drawing of Samuel and Margaret Wood’s cabin on Massachusetts Street, ca 1855. Image courtesy of David Aspelin.

At one point, Margaret Wood’s father, William Lyon, who lived west of town (on present-day Queen’s Road), feared that his daughter would be harmed or jailed for sheltering a fugitive slave, so he came into Lawrence to get his daughter. Margaret shed tears of concern for Lizzie noting that Lizzie’s back was covered in scars and welts from the whip of her slave owner.

With the help of Lawrence Tribune editor John Speer, another abolitionist, John Archibald, removed Lizzie from Wood’s home and led her a mile west on California Road (now 6th Street), pointing the way for her to go to Topeka.

But Lizzie soon found her way back to Lawrence, and in a few days, she reached the home of abolitionist S. J. Willes. She told him that she was a free woman and needed work and a place to stay. Willes took her in, fed her, and one of his neighbors, Mrs. Litchfield, hired her.

But eventually, Lizzie’s location again became known and pro-slavery men appeared at Willes’ door demanding Lizzie’s release. Gun in hand, Willes kept them temporarily at bay, but the question remained: Was Lizzie a slave or a free person of color?

With the help of Lawrence Tribune editor John Speer, another abolitionist, John Archibald, removed Lizzie from Wood’s home and led her a mile west on California Road (now 6th Street), pointing the way for her to go to Topeka.

But Lizzie soon found her way back to Lawrence, and in a few days, she reached the home of abolitionist S. J. Willes. She told him that she was a free woman and needed work and a place to stay. Willes took her in, fed her, and one of his neighbors, Mrs. Litchfield, hired her.

But eventually, Lizzie’s location again became known and pro-slavery men appeared at Willes’ door demanding Lizzie’s release. Gun in hand, Willes kept them temporarily at bay, but the question remained: Was Lizzie a slave or a free person of color?

When pro-slavers threatened to burn down Lawrence if she was not returned to her owner. Dr. J.N.O.P. Wood suggested a compromise. He would keep Lizzie for six weeks, pay her $1 per day, and if no one claimed her during that time, she would be considered free. But people accused him of trying to stir up trouble before the election.

Meanwhile, a group of Lawrence abolitionists held a committee meeting to discuss what to do. Their general sentiment was that they suspected that Lizzie’s owner probably sent her to Lawrence as a decoy. They feared that if she were not sent back to her owner, Lawrence “might be one vast heap of smoking ruins.”

At that point, only John Doy and Charles Stearns still felt the need to protect Lizzie. So the next morning, they went to the cabin where she was staying to ask her directly if she wanted to be free. Her lukewarm answer left them puzzled:

“I wish to be free, but if I must go back,

I might as well submit to it.”

Meanwhile, a group of Lawrence abolitionists held a committee meeting to discuss what to do. Their general sentiment was that they suspected that Lizzie’s owner probably sent her to Lawrence as a decoy. They feared that if she were not sent back to her owner, Lawrence “might be one vast heap of smoking ruins.”

At that point, only John Doy and Charles Stearns still felt the need to protect Lizzie. So the next morning, they went to the cabin where she was staying to ask her directly if she wanted to be free. Her lukewarm answer left them puzzled:

“I wish to be free, but if I must go back,

I might as well submit to it.”

Finally, three pro-slavery men took Lizzie to Shawnee Mission, the seat of the Kansas territorial court, where Judge Lecompte ruled that Lizzie was a slave and should be returned to her slaveholder. And so, after a brief taste of freedom, Lizzie was condemned to a life of slavery. As a result of this failed rescue attempt, agents on the Douglas County Underground Railroad realized they needed to become more organized.

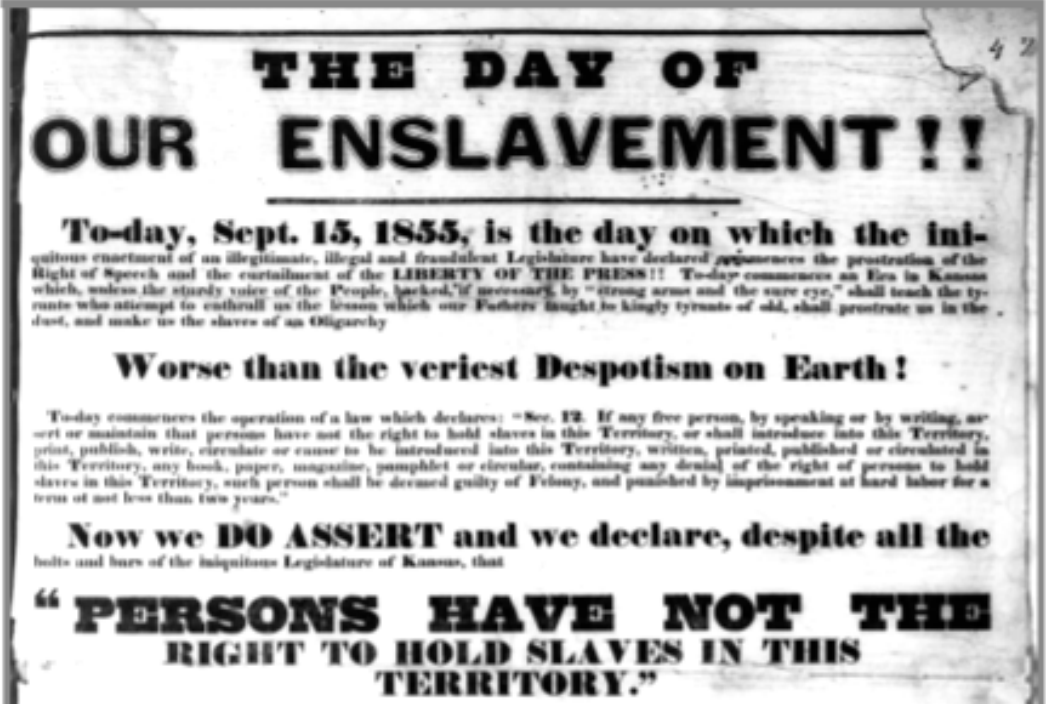

Newspaper clipping: Editor John Speer defies the Fugitive Slave Law, in Lawrence Tribune, September 15, 1855. John Speer was a free state supporter and early resident of Lawrence, Kansas Territory. He was a journalist and editor and was involved in numerous free-state activities.

Stop 4

Abbott UGRR Station

821 Vermont St. Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSAbbott UGRR Station

821 Vermont St. Lawrence, KS

From Massachusetts Street, drive one block south, turn right onto 8th Street, then turn left onto Vermont Street. Park near the vacant lot between 809 and 813 Vermont St. The Abbott’s home (no longer standing) was located somewhere on Vermont St. between 6th and 11th Streets. They also sheltered freedom seekers at their country home.

Photograph of James B. Abbott (ca. 1860 and 1870). Courtesy of Kansas Memory, Kansas Historical Society

Photograph of Elizabeth Ann Watrous Abbott (ca. 1860 and 1880). Courtesy of Kansas Memory, Kansas Historical Society

Around 1858, two teenage boys, about 14 and 18, were sheltered by abolitionists James B. and Elizabeth Abbott in their home on Vermont Street. After several days, the younger boy, tired of having to stay indoors and being waited on by Mrs. Abbott,

declared he would go outside into the fresh air. Despite Mrs. Abbott’s protests, he went into the backyard and the other boy soon followed. She recalled:

“They lingered as though the sunshine and fresh air was so good. It seemed pitiful to see their desire for liberty.”

declared he would go outside into the fresh air. Despite Mrs. Abbott’s protests, he went into the backyard and the other boy soon followed. She recalled:

“They lingered as though the sunshine and fresh air was so good. It seemed pitiful to see their desire for liberty.”

When her husband came home, Mrs. Abbott told him what the boys had done and Mr. Abbott decided that both boys would need to be moved that night as he feared one of the neighbors might have seen them and reported them to the authorities.

If so, that would have meant the boys could have been captured and returned to their slaveholders, and the Abbotts would have each faced a fine of $1,000 and six months in jail for each “offense.” So, that night Mr. Abbott took the boys to the next station that Mrs. Abbott thought was Joel Grover’s stone barn (see Stop 9).

If so, that would have meant the boys could have been captured and returned to their slaveholders, and the Abbotts would have each faced a fine of $1,000 and six months in jail for each “offense.” So, that night Mr. Abbott took the boys to the next station that Mrs. Abbott thought was Joel Grover’s stone barn (see Stop 9).

Stop 5

Tappan UGRR Station

501 Nigel Dr. Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSTappan UGRR Station

501 Nigel Dr. Lawrence, KS

Drive to the next site using your map all the way to Peterson Park and turn left onto Peterson Road. Tappan’s 160-acre claim on the left extended from North Iowa Street to just past Edinburgh Drive. Find a place to park near the 2300 block of Peterson Road.

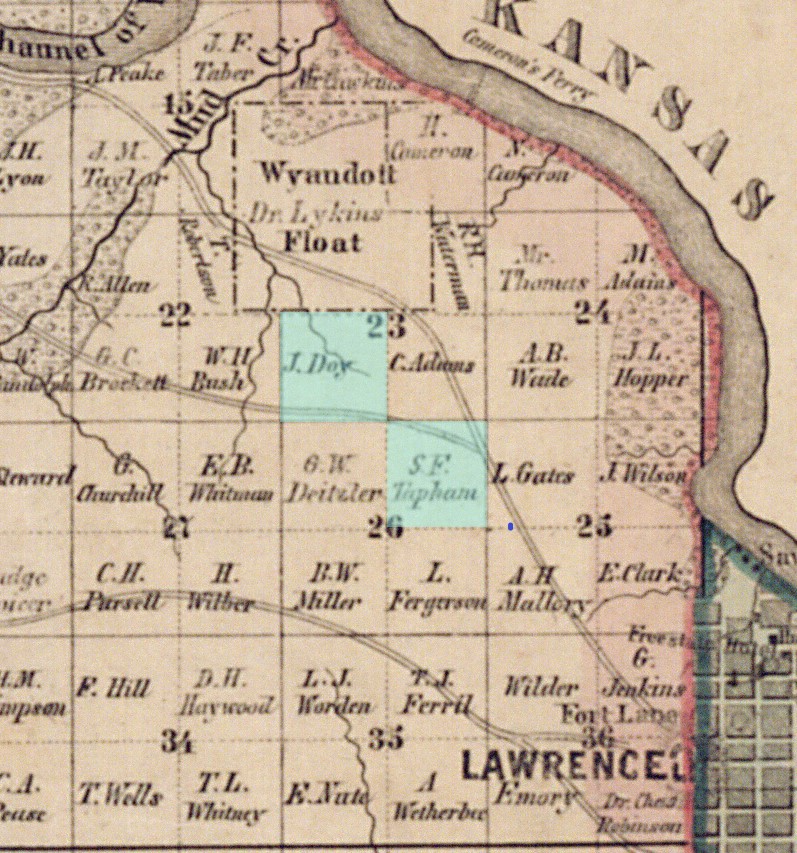

Properties of Tappan [sic], Doy, Adams, and Deitzler in the 1857 Douglas County Kansas Territory map by J. Cooper Stuck. Courtesy of Kansas Memory, Kansas Historical Society.

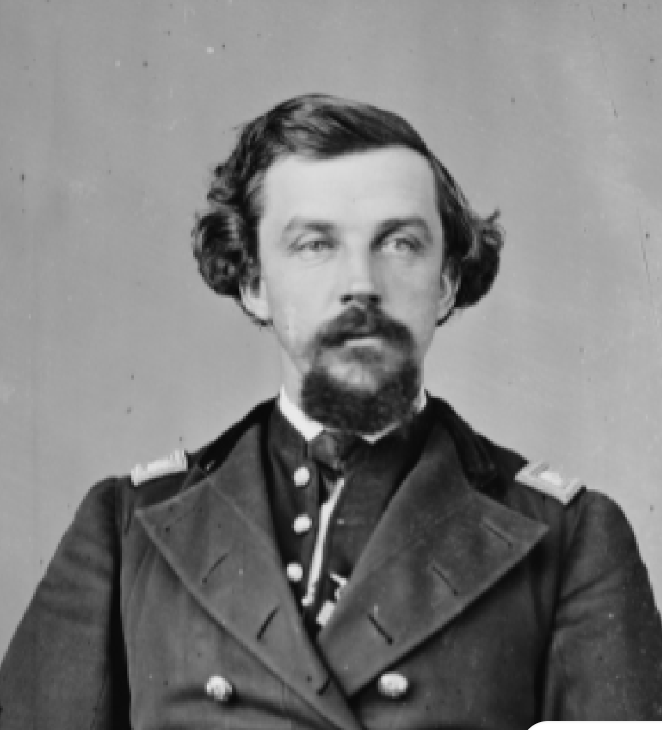

Photographs of Samuel F. Tappan (ca. 1865). Wikipedia, public domain.

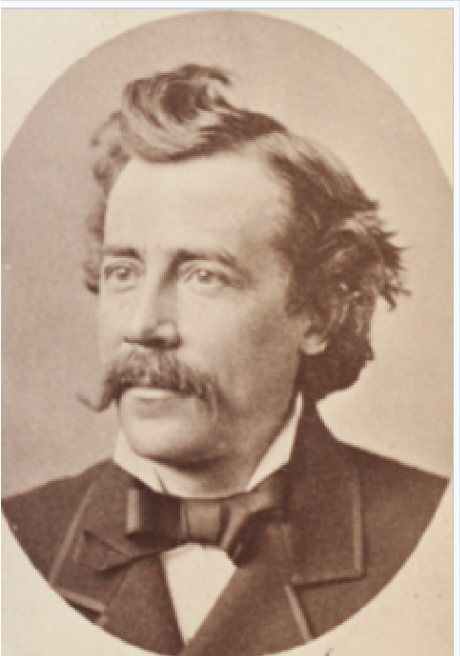

Photographs of Lewis N. Tappan (ca. 1877). Wikipedia, public domain

Samuel Tappan, a reporter, came to Lawrence in 1854 with the First Emigrant Aid party and pre-empted property on the NE quarter of Section 26 in Douglas County southeast of Dr. John Doy’s property.

In 1857, Lewis N. Tappan, Sam’s cousin, came to live with him to improve his health. Coming from New England as a family of abolitionists, it didn’t take long before Lewis got involved in the Free State cause. Their cabin became a UGRR station.

In January 1859, Lewis wrote a letter about two freedom seekers from Missouri who came to the Tappan farm one evening when Sam was away from home. Lewis noticed two Black men approaching him in the farmyard. They indicated they were sent to the Tappans by Mayor James Blood of Lawrence. They had walked twenty miles that day and were exhausted.

In 1857, Lewis N. Tappan, Sam’s cousin, came to live with him to improve his health. Coming from New England as a family of abolitionists, it didn’t take long before Lewis got involved in the Free State cause. Their cabin became a UGRR station.

In January 1859, Lewis wrote a letter about two freedom seekers from Missouri who came to the Tappan farm one evening when Sam was away from home. Lewis noticed two Black men approaching him in the farmyard. They indicated they were sent to the Tappans by Mayor James Blood of Lawrence. They had walked twenty miles that day and were exhausted.

Lewis realized the men were freedom seekers on the Underground Railroad, so he invited them into the cabin and made a bed for them. Sam soon came home and upon opening the door exclaimed, “What’s that?” pointing to the sleeping men. Lewis replied “There is $3,000 worth of property. . . . I have taken [in] transient boarders.” Sam replied:

“This is a dangerous neighborhood.

They must soon be out of it.”

[Sam was no doubt referring to the recent January 25th ambush by pro-slavery forces of their neighbor, John Doy, on his UGRR journey with two wagons full of former slaves, as well as to the previous attack in their neighborhood by pro-slavery men in 1856].

So, they woke the men at 3 a.m. and pointed the way toward Topeka where other UGRR stations would welcome them. A few months later, the Tappan cousins heard that the two men had safely reached Nebraska.

“This is a dangerous neighborhood.

They must soon be out of it.”

[Sam was no doubt referring to the recent January 25th ambush by pro-slavery forces of their neighbor, John Doy, on his UGRR journey with two wagons full of former slaves, as well as to the previous attack in their neighborhood by pro-slavery men in 1856].

So, they woke the men at 3 a.m. and pointed the way toward Topeka where other UGRR stations would welcome them. A few months later, the Tappan cousins heard that the two men had safely reached Nebraska.

Stop 6

Doy UGRR Station

325 Arrowhead Dr. Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSDoy UGRR Station

325 Arrowhead Dr. Lawrence, KS

Drive further west along Peterson Road. After passing Edinburgh Drive, notice the existing 1870s two-story rock house on your right. Dr. Doy’s 160-acre property began near 2930 Peterson Road and extended to Kasold Drive. Note the JOHN DOY COURT street sign on your right in his honor. Find a place to park, perhaps on north Arrowhead Drive, near where Doy’s original house and barn once stood. The archeological ruins are on the National Park Service Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

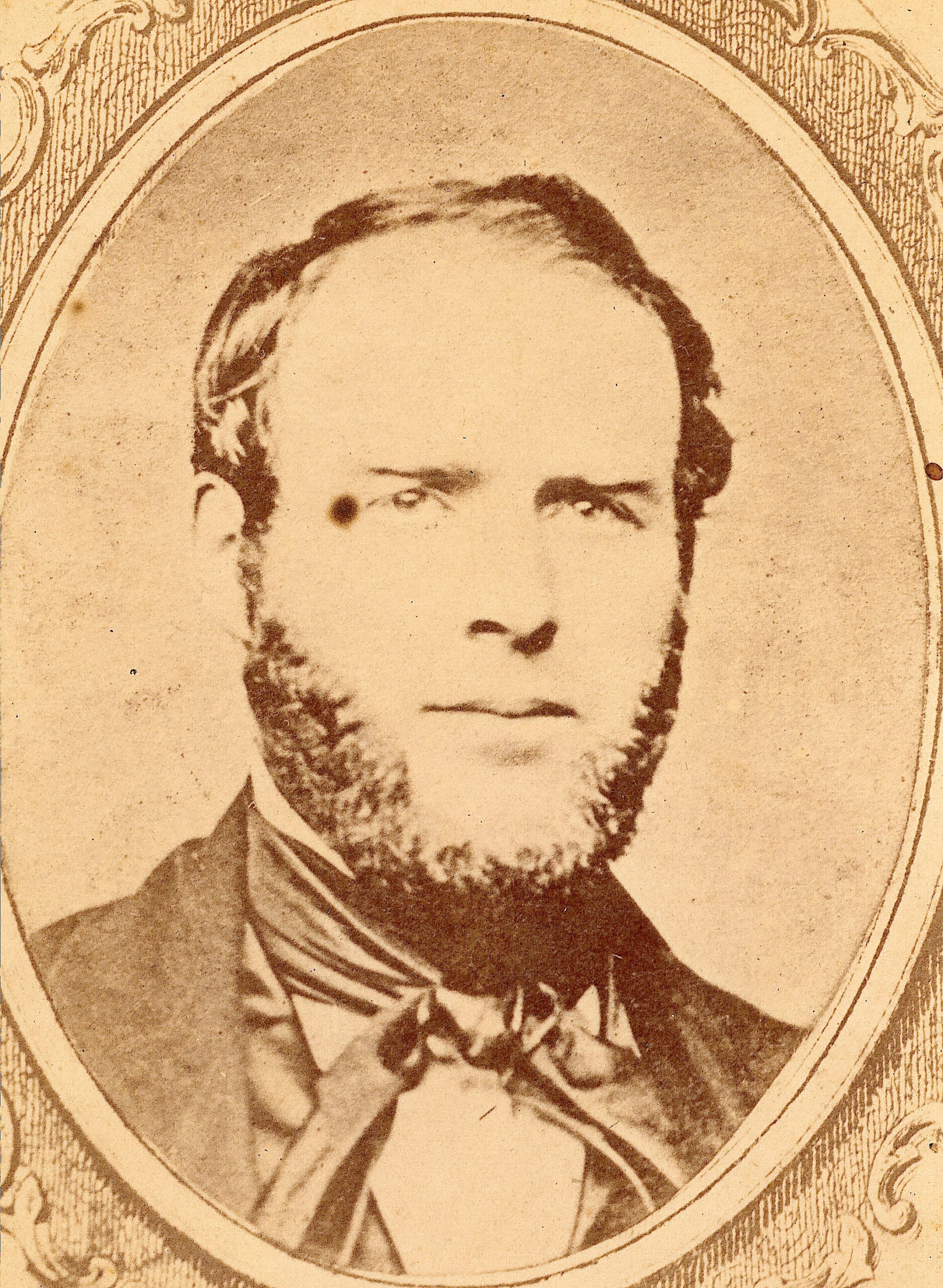

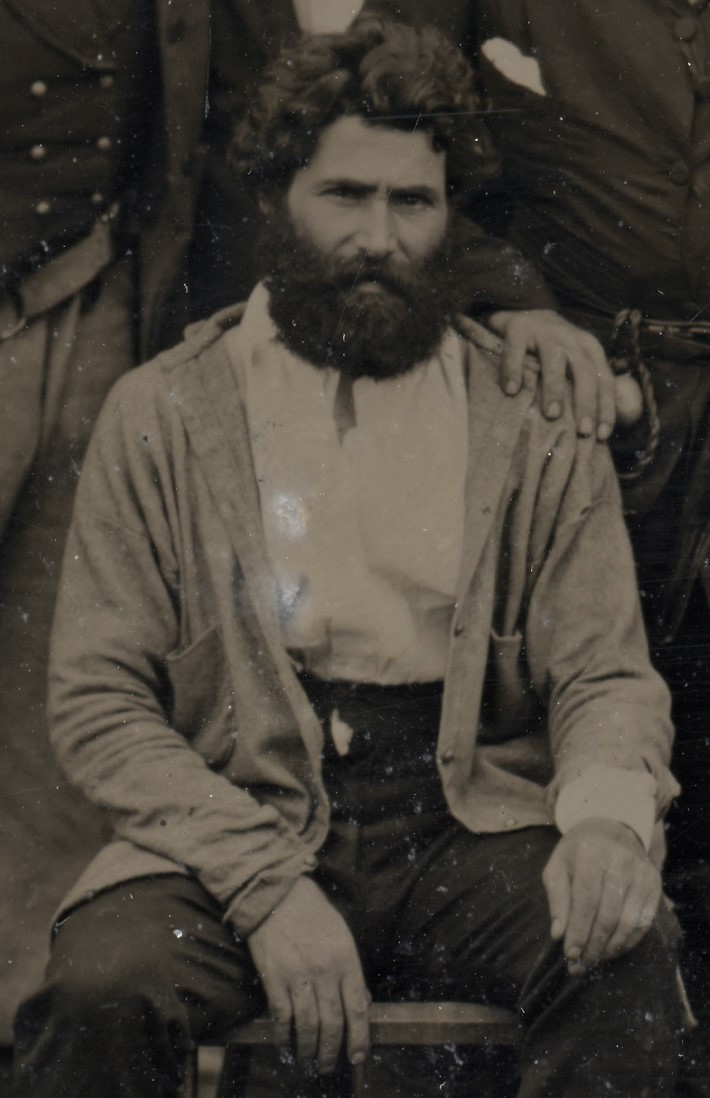

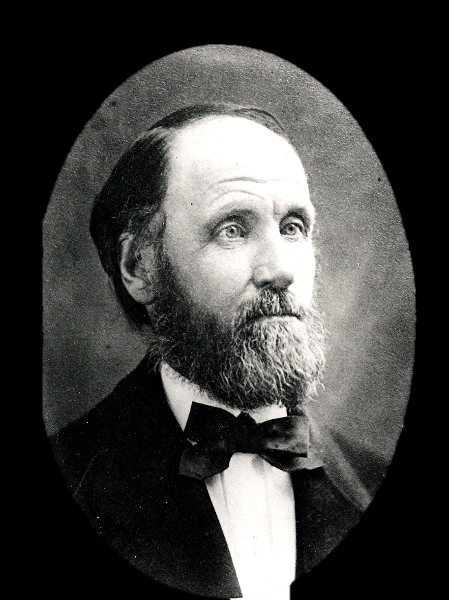

Detail image of Dr. John Doy from "John Doy and Rescue Party," ambrotype by A.G. DaLee, July 1859, KansasMemory, Item #90198.

Dr. John Doy, who was born in England, married Jane Dunn in 1836 and they raised 11 children. In 1854, Dr. Doy arrived in Lawrence with the First Massachusetts (New England) Emigrant Aid party and pre-empted 160 acres (along Peterson Road that extended to Kasold Drive), where he first built a log cabin and later added a two-story house, barn, and stable just north of the house.

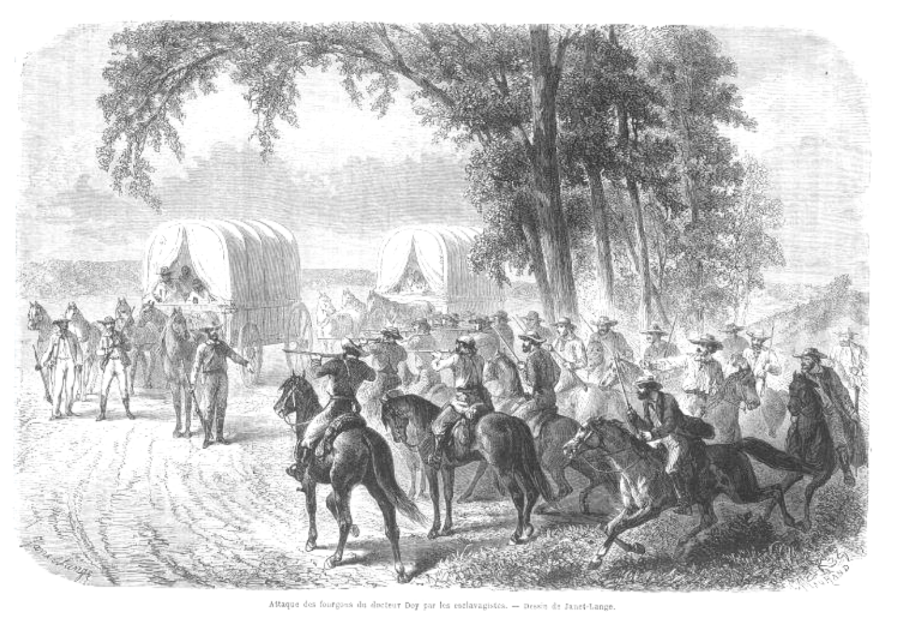

In 1858, James B. Abbott asked Dr. Doy to become a UGRR conductor and take 13 Missouri freedom seekers from their hide-out in Lawrence north as far as Holton, Kansas. To prepare for this trip, Dr. Doy scouted a dry run in December 1858 to find stopping places along the way to Holton. On January 25, 1859, Doy, his son Charles, and a driver, Mr. Clough, started the journey with the freedom seekers in two covered wagons.

Unfortunately, when the group was about 12 miles north of Lawrence, an armed mob of pro-slavery men, including Jake Herd, ambushed them. They first took the group to Weston, Missouri, where townspeople jeered them. Sadly, Doy’s freedom-seeking passengers were returned to slavery, while Dr. John and Charles Doy were imprisoned in filthy, unhealthy conditions in the Platte City jail.

In 1858, James B. Abbott asked Dr. Doy to become a UGRR conductor and take 13 Missouri freedom seekers from their hide-out in Lawrence north as far as Holton, Kansas. To prepare for this trip, Dr. Doy scouted a dry run in December 1858 to find stopping places along the way to Holton. On January 25, 1859, Doy, his son Charles, and a driver, Mr. Clough, started the journey with the freedom seekers in two covered wagons.

Unfortunately, when the group was about 12 miles north of Lawrence, an armed mob of pro-slavery men, including Jake Herd, ambushed them. They first took the group to Weston, Missouri, where townspeople jeered them. Sadly, Doy’s freedom-seeking passengers were returned to slavery, while Dr. John and Charles Doy were imprisoned in filthy, unhealthy conditions in the Platte City jail.

Illustration of the proslavey ambush of John Doy's party on January 25, 1859 near Oskaloosa, K.T. by Janet Lange in "Le Tour du Monde," 1862, Vol 5, page 373, Hathi Trust.

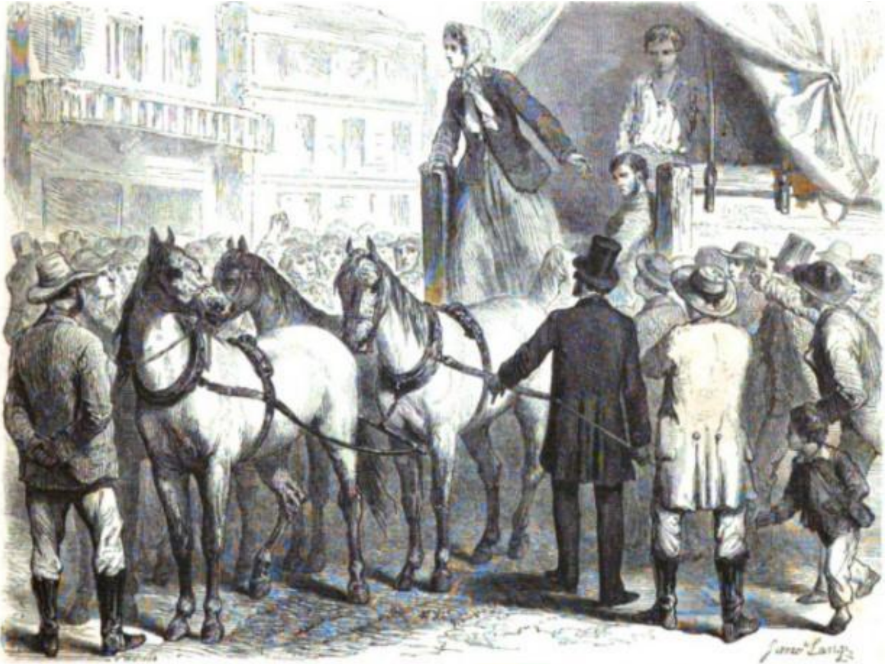

After a trial, Charles was released, but John Doy was taken to the jail in St. Joseph, Missouri awaiting a Supreme Court trial. His wife, Mrs. Jane (Dunn) Doy insisted on accompanying him from Platte City to St. Joseph and spoke bravely:

“Men of Platte City, when I married my husband twenty-six years ago, I promised to stick by him while he had a button to his coat and I mean to do it. Do you think I would desert him in this extremity? If you do you are quite mistaken.”

Illustration, "Mrs. John Doy Speaks boldly to the Men of Platte City, Missouri (1859) by Janet-Lange in Le Tour du Monde, 1862. (Vol. 5 p 377), Hathi Trust.

Days before the Supreme Court trial took place, ten brave men from Lawrence, later called “The Immortal Ten,” conducted an ambitious rescue of Dr. Doy from the jail. They brought him back to Lawrence, where A. G. DaLee photographed them on Massachusetts Street in July 1859.

Painting, "The Immortal Ten, "Kansas Abolitionists After their Rescue of Dr. John Doy." 1859. [oil on canvas 36' x 48'] by Artist Wayne Wildcat.

Stop 7

Grover Barn UGRR Station

2819 Stone Barn Terrace, Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSGrover Barn UGRR Station

2819 Stone Barn Terrace, Lawrence, KS

From Peterson Rd., turn left on Kasold, drive south a distance, and turn left on Clinton Parkway/23rd St. Turn right on Lawrence Ave. and park in the lot at Grover’s Barn. Read the three interpretative panels and take a brochure near the kiosks. View or walk around the limestone barn. The interior of the barn will be open to the public in the future.

Photo of Joel Grover

Photo of Mrs. Emily (Hunt) Grover

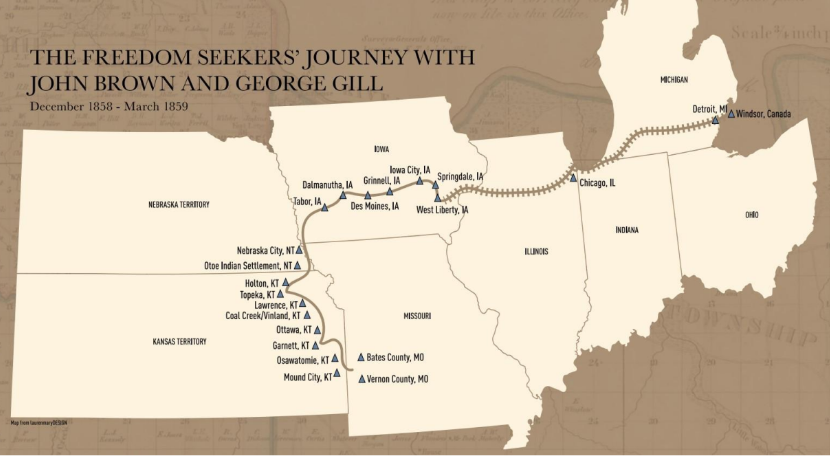

On the same day that John Doy’s Underground Railroad group left Lawrence, abolitionist John Brown led another well-documented journey. One of Brown’s men, George Gill, was approached in southern Kansas by Jim Daniels, an enslaved man who had been given permission by his owner to sell brooms at Christmas. Daniels explained that he, his pregnant wife, Narcissa, and their two children were about to be sold (and possibly separated) to settle an estate. Jim Daniels asked for John Brown to liberate his family and Sam Harper. So the next night, John Brown and his men went to their dwellings in Vernon and Bates counties, Missouri where they rescued 11 freedom seekers and began their Underground Railroad journey. Jane Harper recalled:

“Cap’n Brown asked if we wanted to be free

and told us he would take us where we would be free.”

“Cap’n Brown asked if we wanted to be free

and told us he would take us where we would be free.”

The group stopped for about a month at cabins in Franklin County, K.T., where Narcissa Daniels gave birth to a baby boy. They named him “John Brown Daniels” in honor of John Brown. Concerned for the health of the mother, Brown insisted that they stay there long enough for Mrs. Daniels to recover. John Brown said:

“I would no more endanger a poor Negro woman

than a Princess of the realm.”

Next, the group traveled to other Kansas stations, including those of Ottawa “Tauy” Jones, the Amasa Soule family, and the James B. Abbott family.

“I would no more endanger a poor Negro woman

than a Princess of the realm.”

Next, the group traveled to other Kansas stations, including those of Ottawa “Tauy” Jones, the Amasa Soule family, and the James B. Abbott family.

Photo of Grover Barn, south side, ca. 1890. The wagons arriving with freedom seekers likely entered the south side of the banked barn at night. Image: Courtesy of Inga Waite.

At the end of January 1859, the group arrived at Joel and Emily (Hunt) Grover’s barn about 3 miles southwest of Lawrence. The freedom seekers cooked while John Brown went into Lawrence to sell the oxen and get provisions.

After a few days’ stay, the group left with John Brown and his men. They traveled through Kansas and Nebraska to West Liberty, Iowa by covered wagon and then by train to Chicago, Illinois. There, the group took another train to Detroit, Michigan, arranged by detective Allen Pinkerton. On March 12, 1859, the freedom seekers crossed the Detroit River into Windsor, Canada. (Slavery was outlawed in Canada in 1834.)

After a few days’ stay, the group left with John Brown and his men. They traveled through Kansas and Nebraska to West Liberty, Iowa by covered wagon and then by train to Chicago, Illinois. There, the group took another train to Detroit, Michigan, arranged by detective Allen Pinkerton. On March 12, 1859, the freedom seekers crossed the Detroit River into Windsor, Canada. (Slavery was outlawed in Canada in 1834.)

Formal photograph of Sam and Jane Harper. Mr. and Mrs. Harper were two of the 12 freedom seekers who traveled the UGRR from Missouri to Windsor, Ontario, Canada, with John Brown and his men in 1858-1859, by Murdoch Bros., Windsor, Canada, 1894.

Map showing the Underground Railroad Journey from Vernon County, Missouri to Canada [Source: Guardians of Grover Barn and Watkins Museum].

Stop 8

Cordley UGRR Station

2030 Vermont St. Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSCordley UGRR Station

2030 Vermont St. Lawrence, KS

Drive east on Clinton Parkway/23rd St. past Iowa and turn left onto Vermont St. Park near 2023 Vermont, the site of the Cordley cottage (no longer standing) which was outside the Lawrence city limits in 1859.

Photographs of Rev. and Mrs. Richard Cordley, 1866, by J. Lee Knight. Courtesy of Kansas Memory, Kansas Historical Society.

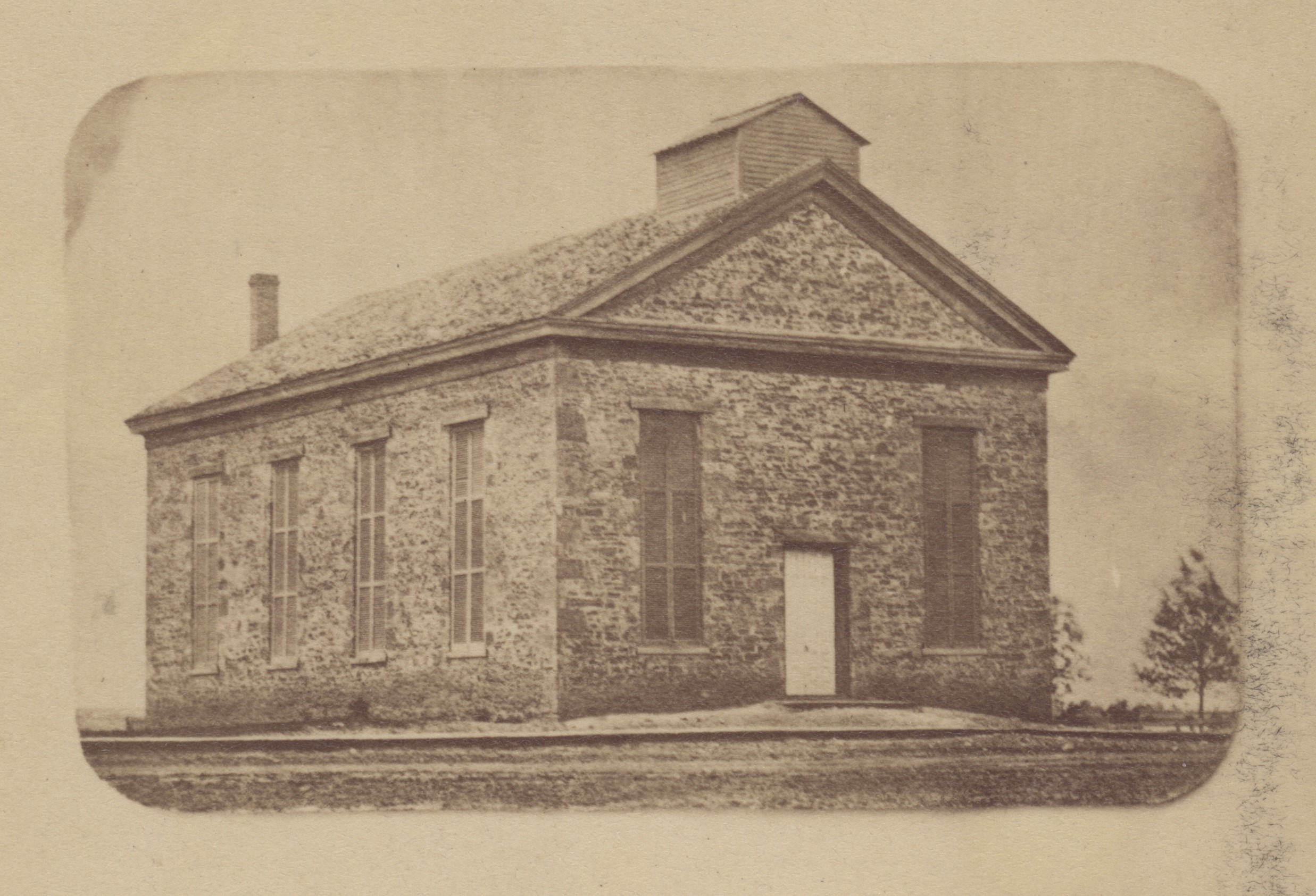

Plymouth Congregational Church, the first stone church build in 1857 (1866 composite photo). Courtesy of Kansas Memory, Kansas Historical Society.

In the summer of 1859, Rev. Richard Cordley, a Congregational minister, and his wife, Mary Minta Cordley, were living in a rented two-story stone cottage south of the city limits of Lawrence (in the 2000 block of Vermont Street today).

One night, William R. Monteith, an abolitionist and station master, knocked on their door. He lived about four miles southwest of Lawrence on the Wakarusa River (on the NE ¼ of Sec 15). He asked the Cordley couple if they would shelter a young freedom seeker, another “Lizzie,” who had been enslaved in Missouri.

When Rev. Cordley was a college student in Michigan, he remembered thinking about the injustice of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and determined that if a fugitive ever came to his door, he would certainly shelter that person. But now he was actually confronted with that choice and he knew, if caught, he and his wife could face six months in jail and a fine of $1,000. He reasoned:

“It is easy to be brave a thousand miles away

but I must now face the question at short range.”

One night, William R. Monteith, an abolitionist and station master, knocked on their door. He lived about four miles southwest of Lawrence on the Wakarusa River (on the NE ¼ of Sec 15). He asked the Cordley couple if they would shelter a young freedom seeker, another “Lizzie,” who had been enslaved in Missouri.

When Rev. Cordley was a college student in Michigan, he remembered thinking about the injustice of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and determined that if a fugitive ever came to his door, he would certainly shelter that person. But now he was actually confronted with that choice and he knew, if caught, he and his wife could face six months in jail and a fine of $1,000. He reasoned:

“It is easy to be brave a thousand miles away

but I must now face the question at short range.”

After a brief discussion with Mary, the Cordleys agreed to provide shelter for this freedom seeker. So, Lizzie lived with them for several months. She helped cook and clean for which she was paid. Rev. Cordley later wrote:

“We never had a more competent help than

Lizzie proved to be . . . she said the work

of our little family was like play to her.”

At the end of the summer, Mr. Monteith returned to the Cordley house to retrieve Lizzie, because he and his family had moved into Lawrence and Lizzie could now stay with them.

Then in the fall of 1859, Mr. Monteith arrived with Lizzie a second time at the Cordley’s home. This time they were both disguised in large men’s fur overcoats. A worried Monteith said that the slave catchers were on their trail and he wondered if the Cordleys would keep Lizzie until about 10 o’clock that night until he could arrange to move her to another Underground Railroad station. They agreed.

At that time, the Cordleys had a couple staying with them, Rev. and Mrs. William Hayes Ward. They were fearful that the federal marshal could arrive at any time to abduct Lizzie. So the women came up with an ingenious plan to hide her.

“We never had a more competent help than

Lizzie proved to be . . . she said the work

of our little family was like play to her.”

At the end of the summer, Mr. Monteith returned to the Cordley house to retrieve Lizzie, because he and his family had moved into Lawrence and Lizzie could now stay with them.

Then in the fall of 1859, Mr. Monteith arrived with Lizzie a second time at the Cordley’s home. This time they were both disguised in large men’s fur overcoats. A worried Monteith said that the slave catchers were on their trail and he wondered if the Cordleys would keep Lizzie until about 10 o’clock that night until he could arrange to move her to another Underground Railroad station. They agreed.

At that time, the Cordleys had a couple staying with them, Rev. and Mrs. William Hayes Ward. They were fearful that the federal marshal could arrive at any time to abduct Lizzie. So the women came up with an ingenious plan to hide her.

They decided to create a sick room in the bedroom on the second floor, place Mrs. Ward in bed, and pretend she was ill. They placed medicine bottles on her bedside table, and Mrs. Cordley planned to play the part of the “patient’s” caretaker. In the event that the federal marshal or slave catchers arrived, they would quickly hide Lizzie between the mattress and the feather bed under Mrs. Ward. Lizzie agreed to the plan and said:

“I will make myself as small as I ever

can be and I will lie as still as still can be.”

In the meantime, Rev. Cordley and Rev. Ward stayed up late in the downstairs parlor listening for the approach of a wagon. They held their breath when they heard a carriage drive down the remote driveway at about 10 p.m. But then it turned around and went away and they were greatly relieved.

Finally about 12:30 a.m., they heard the approach of a wagon and then a rap at the door. Rev. Cordley opened the door and there stood Mr. Monteith. They summoned Lizzie, said quick goodbyes, and she left to be taken to another Underground Railroad station in Kansas. The Cordleys were relieved to learn months later that Lizzie had made it safely to freedom in Canada.

“I will make myself as small as I ever

can be and I will lie as still as still can be.”

In the meantime, Rev. Cordley and Rev. Ward stayed up late in the downstairs parlor listening for the approach of a wagon. They held their breath when they heard a carriage drive down the remote driveway at about 10 p.m. But then it turned around and went away and they were greatly relieved.

Finally about 12:30 a.m., they heard the approach of a wagon and then a rap at the door. Rev. Cordley opened the door and there stood Mr. Monteith. They summoned Lizzie, said quick goodbyes, and she left to be taken to another Underground Railroad station in Kansas. The Cordleys were relieved to learn months later that Lizzie had made it safely to freedom in Canada.

A few years after “Lizzie” left their home, Rev. Cordley wrote of hiring another, very competent and intelligent domestic servant (probably Mrs. Mary Gregg). She worked in the Cordley’s household for a number of years.

Prior to her escape to Kansas in 1855, she had been enslaved in a Missouri border town by an unknown slaveholder who ranked high in pro-slavery circles. As a house slave, she overheard many secret conversations among pro-slavery men and learned some of their plans. Rev. Cordley wrote that months before Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence on August 21, 1863, Mrs. Gregg used to say that “the bushwhackers were surely coming and the people were very foolish not to be prepared for them.”

Prior to her escape to Kansas in 1855, she had been enslaved in a Missouri border town by an unknown slaveholder who ranked high in pro-slavery circles. As a house slave, she overheard many secret conversations among pro-slavery men and learned some of their plans. Rev. Cordley wrote that months before Quantrill’s raid on Lawrence on August 21, 1863, Mrs. Gregg used to say that “the bushwhackers were surely coming and the people were very foolish not to be prepared for them.”

Stop 9

Cordley Mural

1744 Kentucky St. Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSCordley Mural

1744 Kentucky St. Lawrence, KS

Drive north on Vermont St. and park somewhere north of Cordley School where you can view the mural from a distance off 18th St.

This colorful 20’ x 20’ mural, painted by local artist Dave Lowenstein, illustrates scenes from Rev. and Mrs. Cordley’s story just described. Rev. Cordley (lower left) writes his story; Mrs. Cordley stands with Lizzie (upper center); Lizzie and Mr. Monteith in disguises (center left); and Mrs. Ward in bed (upper left). This school, built in 1915, was named after Rev. Cordley, who served as superintendent of Lawrence schools in 1863.

Stop 10

Miller UGRR Station

1111 E 19th St. Lawrence, KS

DIRECTIONSMiller UGRR Station

1111 E 19th St. Lawrence, KS

Drive south on Vermont St. and turn left onto 19th St. Just past Haskell Ave., enter the shopping mall on your right, and park near the wooden fence at the back. The Miller house is on private property. Walk around the fence and view the home from in front of its sign in the yard.

The Miller house in 1881 showing Mr. and Mrs. Robert Miller (seated) and William and Estella Miller (standing). Courtesy of Dennis Dailey.

The Miller family held very strong antislavery views as free-staters. Josiah Miller, editor of the Lawrence Kansas State Journal, purchased about 40 acres for his parents, Robert and Susannah Miller, on this site, located on the Oregon Trail two miles west of Franklin, a proslavery settlement. His parents and four siblings moved from South Carolina and Illinois in April 1858, and by December, they had built and occupied this home, now on the National Register of Historic Places.

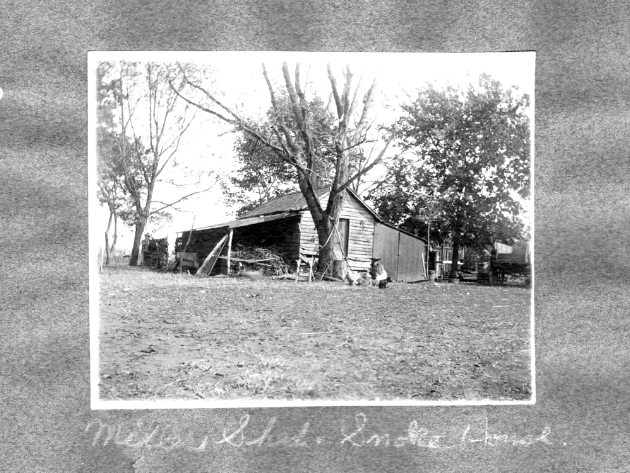

The smokehouse, located in the backyard, is no longer standing. Courtesy of Dennis Dailey.

Based on oral histories and other accounts, the Miller family hid freedom seekers in their backyard smokehouse and wooded grove. Vanroy Miller remembered Robert, his grandfather, describing his fears that he might be found out by proslavery neighbors living nearby. As a small child, Donald Smith and his mother, Vanera Miller Smith, visited the Miller home frequently. Later in life, he also recalled being told that his great-grandfather had helped runaway slaves escape on the Underground Railroad. According to Robert Miller’s 1862 diary entries, he often hired and paid “negro” farmhands.

The Miller home was the first stop for Quantrill and his men (August 21, 1863) on their way into Lawrence for the largest civilian massacre of the Civil War. It is on the National Register of Historic Places.