CARNEGIE BUILDING HERITAGE TOUR

Use this arrow to learn more at each stop.

This tour was underwritten by the Institute of Museum & Library Services.

Note: The locations in this tour are no longer accessible. The tour is presented here for educational purposes only.

The Carnegie Building, located at 200 W. 9th Street in Lawrence, Kansas, like many “Carnegie Libraries” nationwide, was built using donated funds from steel titan Andrew Carnegie in 1904. It has served as the Lawrence Public Library, the Lawrence Art Center, and today it is rented out for events by the Lawrence Parks and Recreation Department. The building itself was added to the National Register of Historic Places as the Old City Library in 1975.

DIRECTIONSOn the second floor of the Carnegie Building is the large Heritage Room. The walls in it – as well as the East Gallery – are lined with plaques and banners that help tell the story of America’s growing pains by focusing on the Kansas experience. Early struggles here included pitting Indigenous Americans against Western Expansion as well as a complicated political battle over slavery’s expansion.

Scroll down to continue the tour.

Stop 1

ATRIUM AND STONE STAIRWELL

ATRIUM AND STONE STAIRWELL

Enter the building via the 9th street entrance.

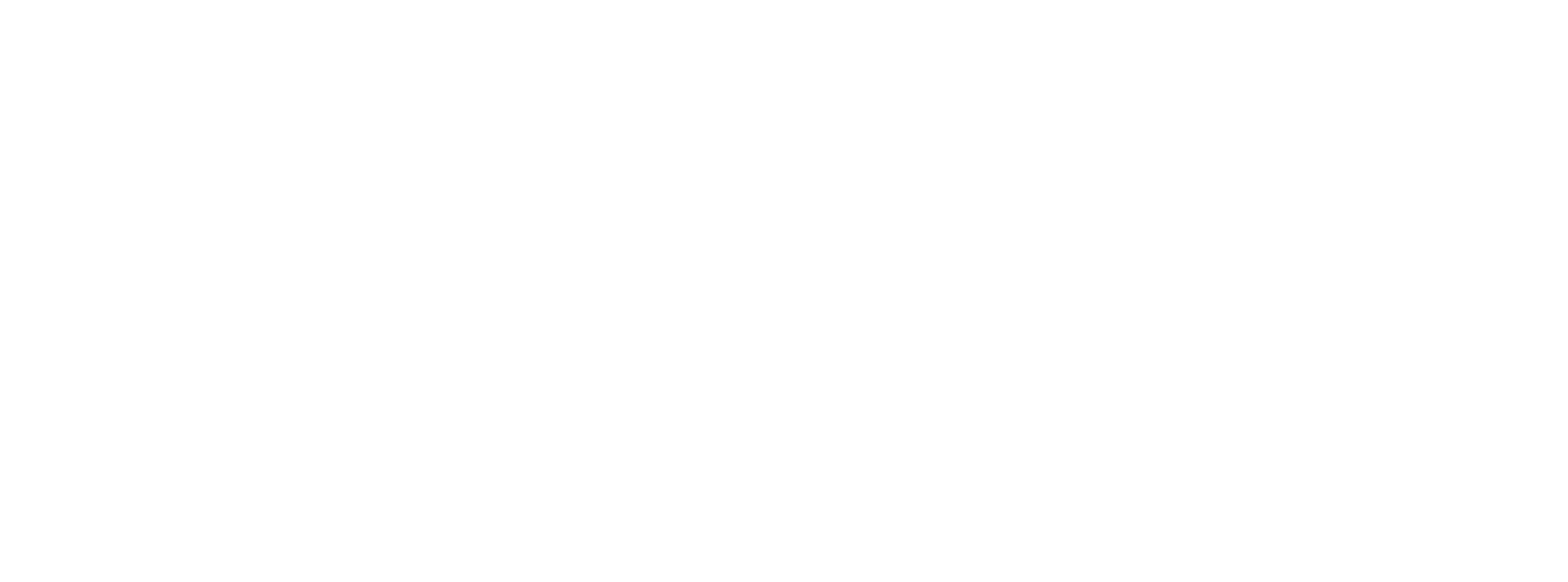

As you make your way to the Heritage Room on the 2nd floor, it may be best to walk through it to view the atrium and stone stairwell first. The massive maps that line the walls on either side place you in geographic context, giving you the perspective of looking east towards the Missouri border or west toward Kansas. They illustrate the places, paths, and people that makeup stories of the struggles which gave Freedom’s Frontier its name.

Stop 2

BELONGING TO THE EARTH

BELONGING TO THE EARTH

Make your way back into the Heritage Room and toward the "Belonging to the Earth" attraction.

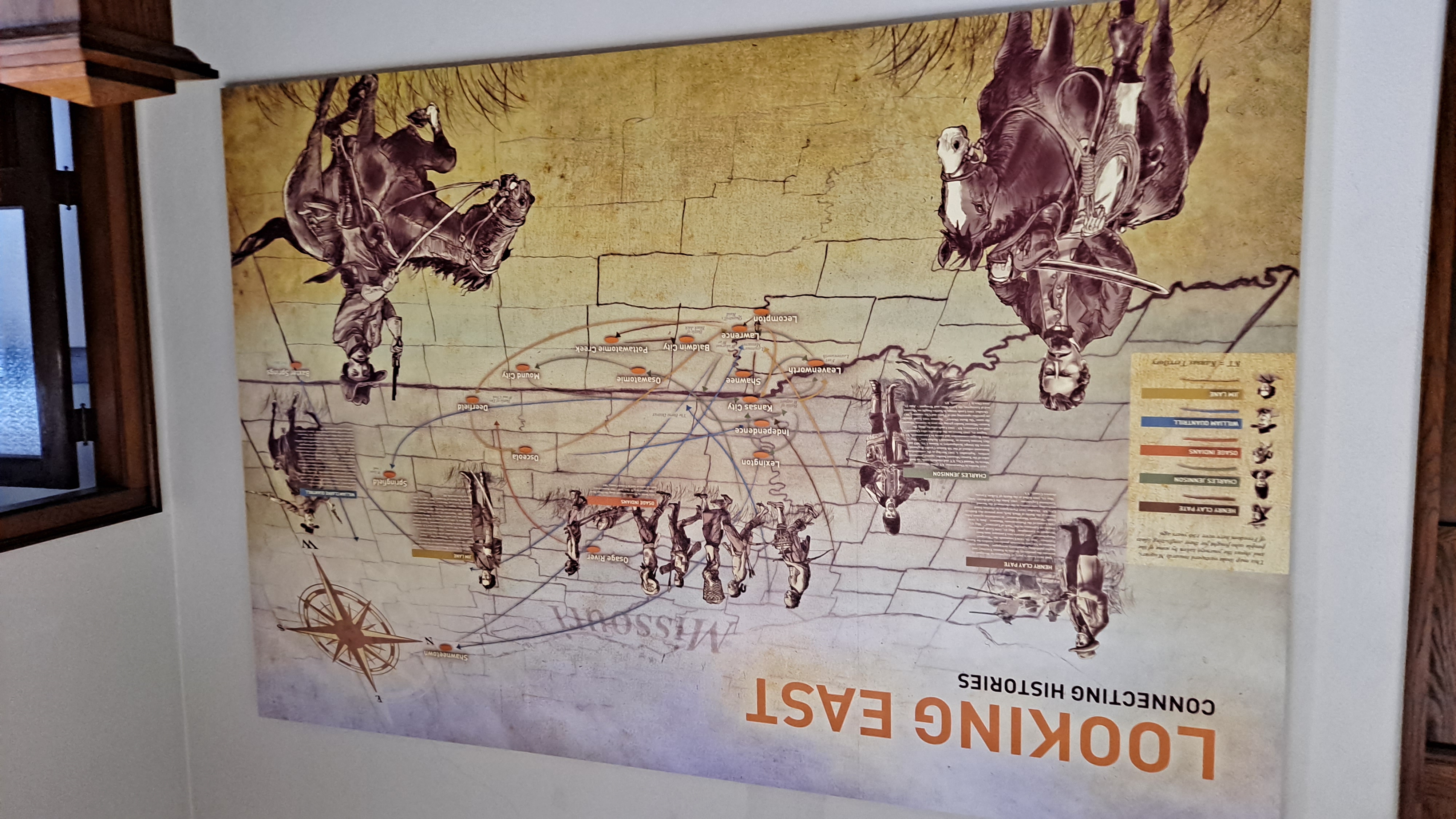

The first figures you should find are Chief White Cloud of the Iowa tribe and US Army surveyor Zebulon Pike in opposition to one another. Chief White Cloud and his people were forcefully relocated from east of the Mississippi River to present-day Nebraska. On the other side, Pike’s explorations of the Louisiana Purchase territory made him an active catalyst of the government’s “manifest destiny” ambitions to push westward from the Mississippi River during the 1800s, eventually forcing tribes like the Iowas further and further west.

Tribal Chief White Cloud tried unsuccessfully to save his people from forced relocation and its accompanying poverty and disease. Congress’s 1830 Indian Removal Act of compelled the Iowas to move west, far away from their traditional hunting lands east of the Mississippi River. Chief White Cloud reluctantly signed a treaty in which the Iowas ceded land in western Iowa and Missouri to the US government. The tribe was then moved to a reservation in present-day Nebraska.

The painting before you is John Gast’s 1872 work, American Progress. The concept of “Manifest Destiny” is represented by an angelic Lady Columbia, a pre-“Lady Liberty” icon, leading Americans westward. Her book and telegraph wire symbolize the government’s view of both its enlightenment and expansion. Native Americans flee before her as white settlers nonchalantly uproot them through technological advancements of the Industrial Revolution. Like most of this painting’s elements, the farmers plowing the field can be both literal and figurative – most settlers believed they were taming the “uninhabited” natural world and reaping the rewards that Divine Providence intended. Citation: American Progress Westward the Course of Destiny by John Gast, 1872.

Stop 3

INDIAN REMOVAL ACT

INDIAN REMOVAL ACT

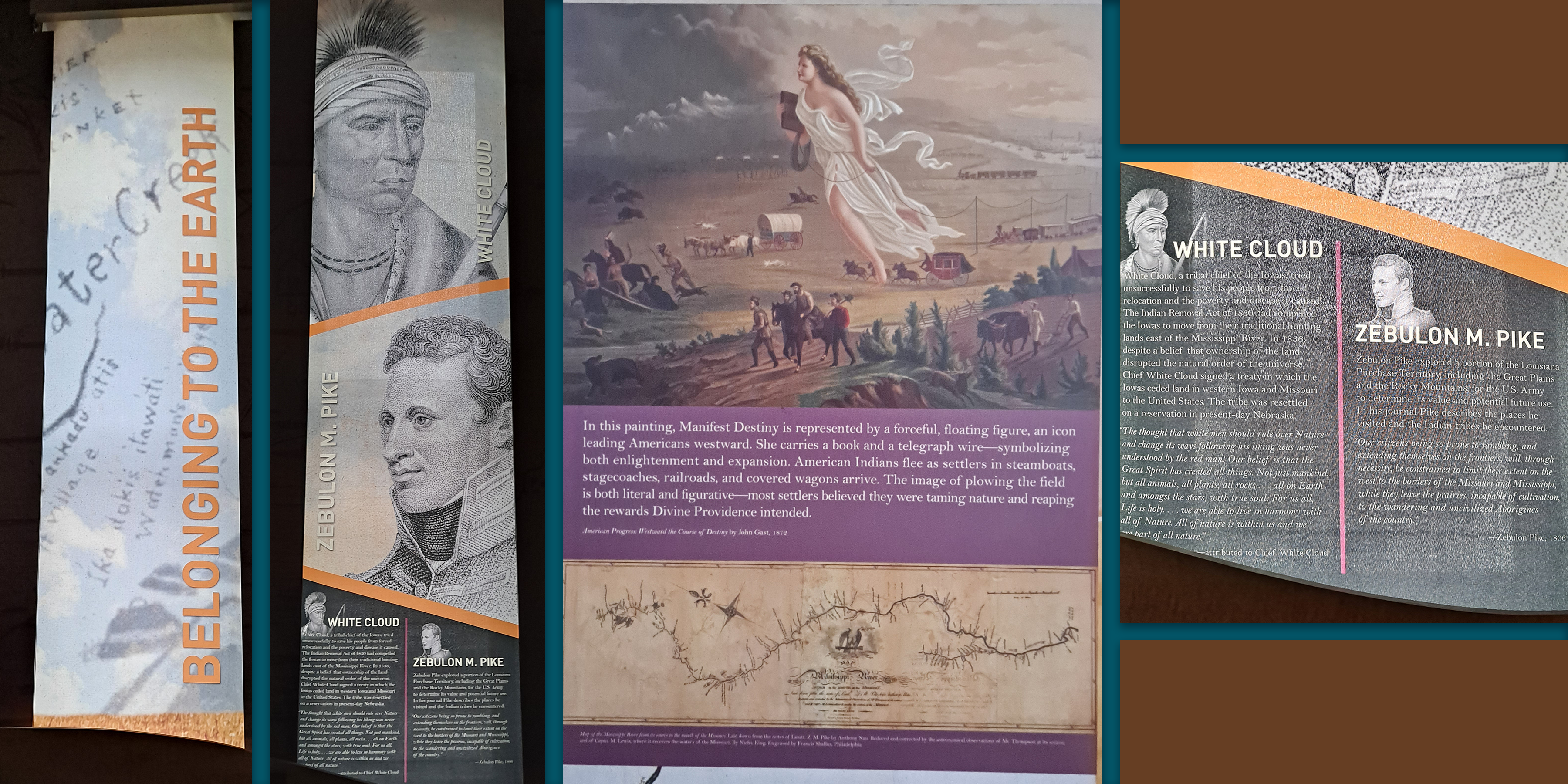

Henry Leavenworth first served in the War of 1812 and then led the Army’s first expedition against Indians on the Great Plains in 1823. To maintain military dominance, he built several army posts at strategic locations, including his namesake Fort Leavenworth on the west bank of the Missouri River in 1827.

After an 1829 outbreak of violence by the Iowa tribes, the Secretary of War reported:

"Colonel Leavenworth ‘assembled… the tribes represented to have been engaged in the affair… to ascertain… whether the Indians or the white people were the aggressors… The Indians… delivered up nineteen of the Ioways… Measures were also taken to ascertain the names of the white men… and (they were) presented to the proper authorities to be dealt with according to law.’"

"Colonel Leavenworth ‘assembled… the tribes represented to have been engaged in the affair… to ascertain… whether the Indians or the white people were the aggressors… The Indians… delivered up nineteen of the Ioways… Measures were also taken to ascertain the names of the white men… and (they were) presented to the proper authorities to be dealt with according to law.’"

Intensifying the clash of cultures, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830 which ordered the relocation of native peoples to western territories. Contested by the Cherokee tribe and found unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court, Jackson pushed forward. The military forced 16,000 Cherokees to march from southeastern states westward beyond the Mississippi River. Along this “Trail of Tears,” more than 25% died from starvation, smallpox, and exhaustion.

The discovery of gold in 1848 at Sutter’s Mill in California escalated migration and the development of overland travel. Treaties with Indian nations were breached, hunting grounds depleted, and the rush to riches contributed to the deaths of thousands of American Indians.

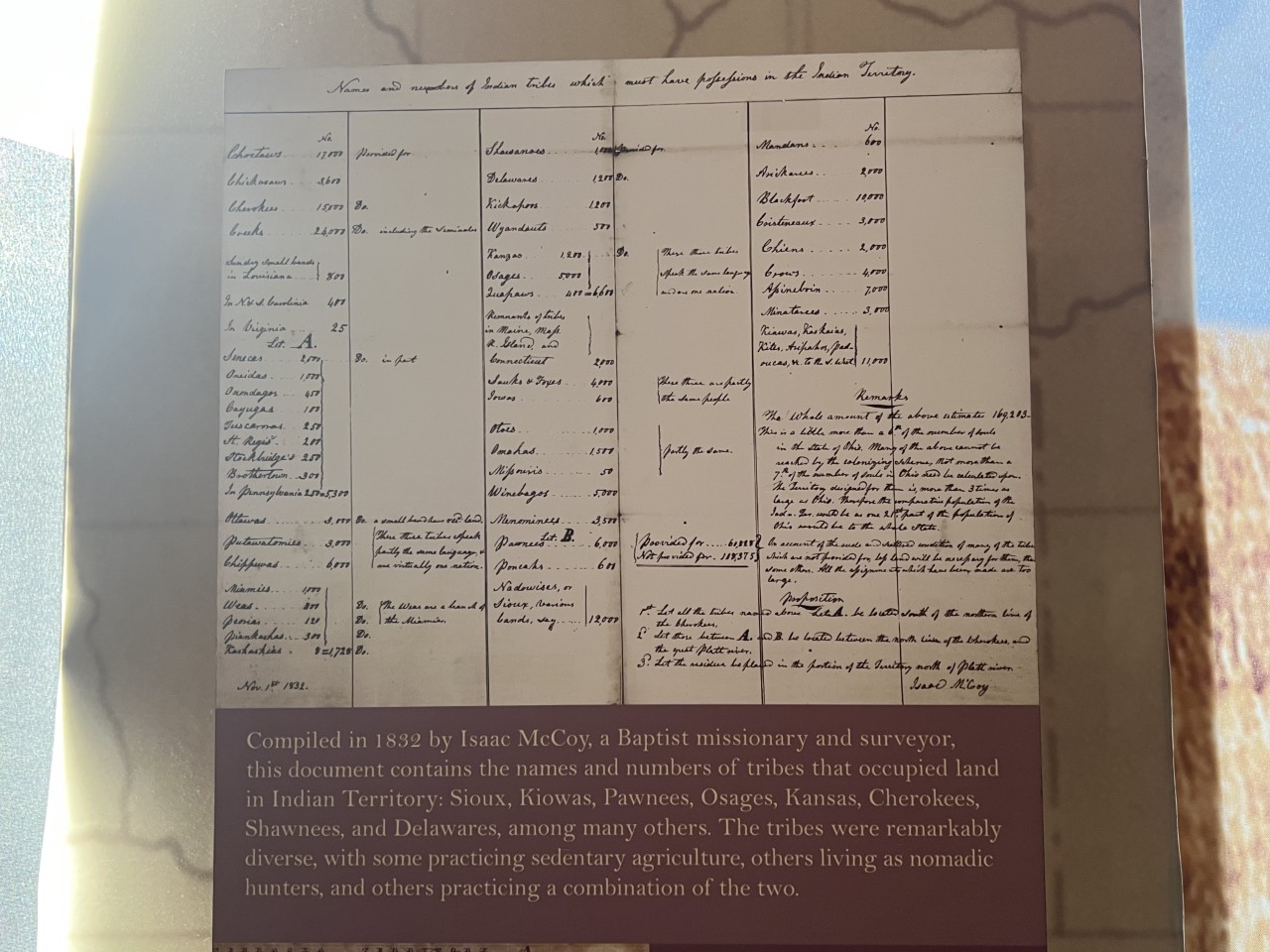

Compiled in 1832 by Isaac McCoy, a Baptist missionary and surveyor, this document contains a population roster of tribes that occupied land in Indian Territory: Sioux, Kiowas, Pawnees, Osages, Kansas, Cherokees, Shawnees, and Delawares, among many others. The livelihoods of these remarkably diverse tribes ranged from sedentary agriculture to fully nomadic hunting.

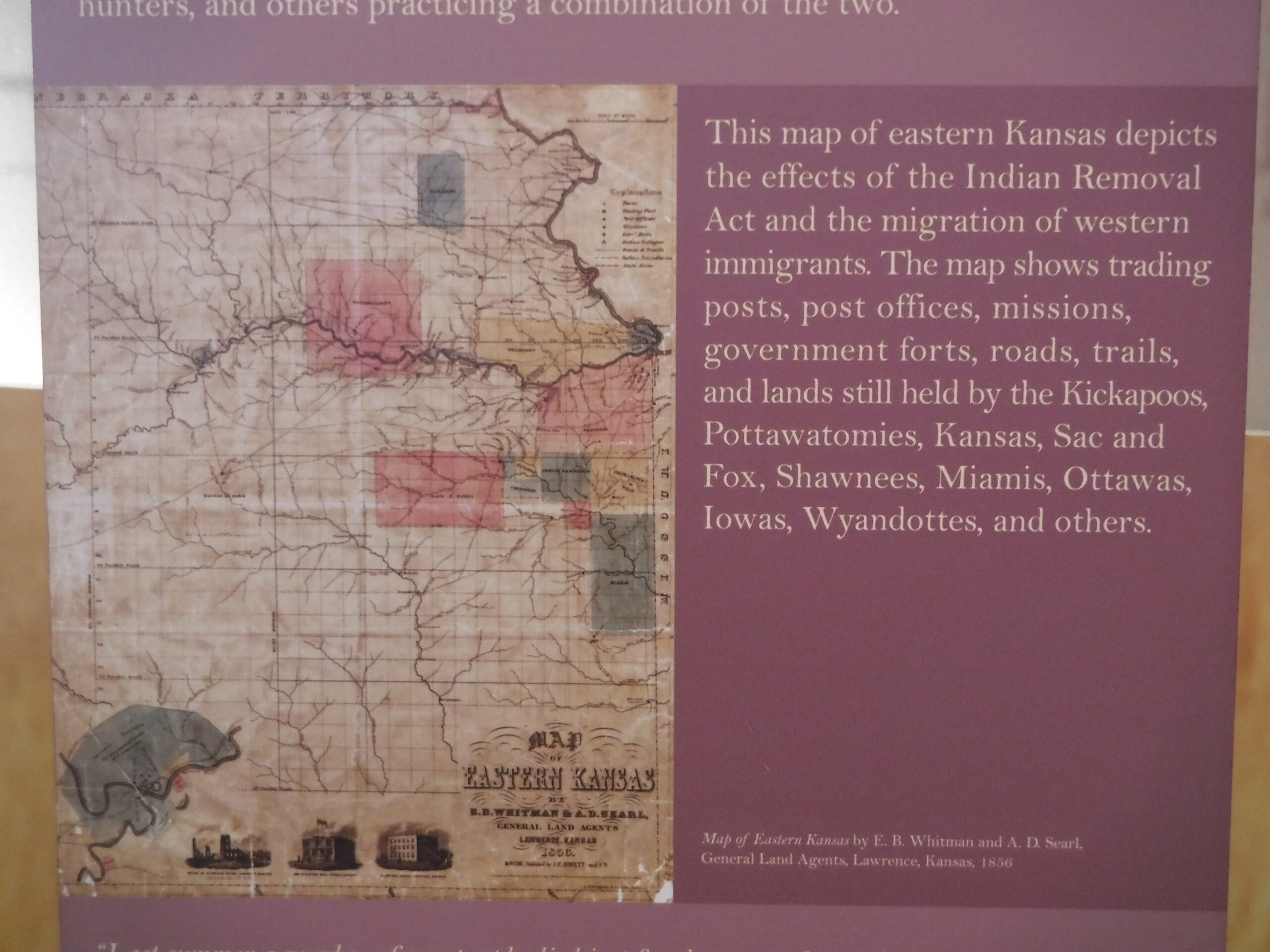

This map of eastern Kansas depicts the effects of the Indian Removal Act and the migration of western immigrants. The map shows trading posts, post offices, missions, government forts, roads, trails, and lands still held by the Kickapoos, Pottawatomie, Kansas, Sac and Fox, Shawnees, Miamis, Ottawas, Iowas, Wyandottes, and others.

Stop 4

DIMINISHED RESERVE

DIMINISHED RESERVE

For generations, Plains Indian tribes like the Kansas, Pawnees, and Osages lived and hunted here. After the 1830 Indian Removal Act, eastern tribes were resettled to land that later became the Kansas and Nebraska Territories. Eager to expand west, the government negotiated treaties and by the end of 1854, the tribes had ceded much of their land. They were forced to Indian Territory mostly in present-day Oklahoma.

Even prior to that, schools were being established to provide religious education and practical job skills for American Indian children, but these schools were also designed to stifle Indigenous cultures.

For decades, Tenskwatawa, ‘The Shawnee Prophet,’ fiercely opposed removal (shortened). His vision went beyond tribe and clan: he exhorted American Indians to practice, protect, and preserve their heritage in the face of this forced assimilation (def). He also warned of the danger posed by internal disputes as they faced these external threats.

For decades, Tenskwatawa, ‘The Shawnee Prophet,’ fiercely opposed removal (shortened). His vision went beyond tribe and clan: he exhorted American Indians to practice, protect, and preserve their heritage in the face of this forced assimilation (def). He also warned of the danger posed by internal disputes as they faced these external threats.

Stop 5

THE KANSAS-NEBRASKA ACT

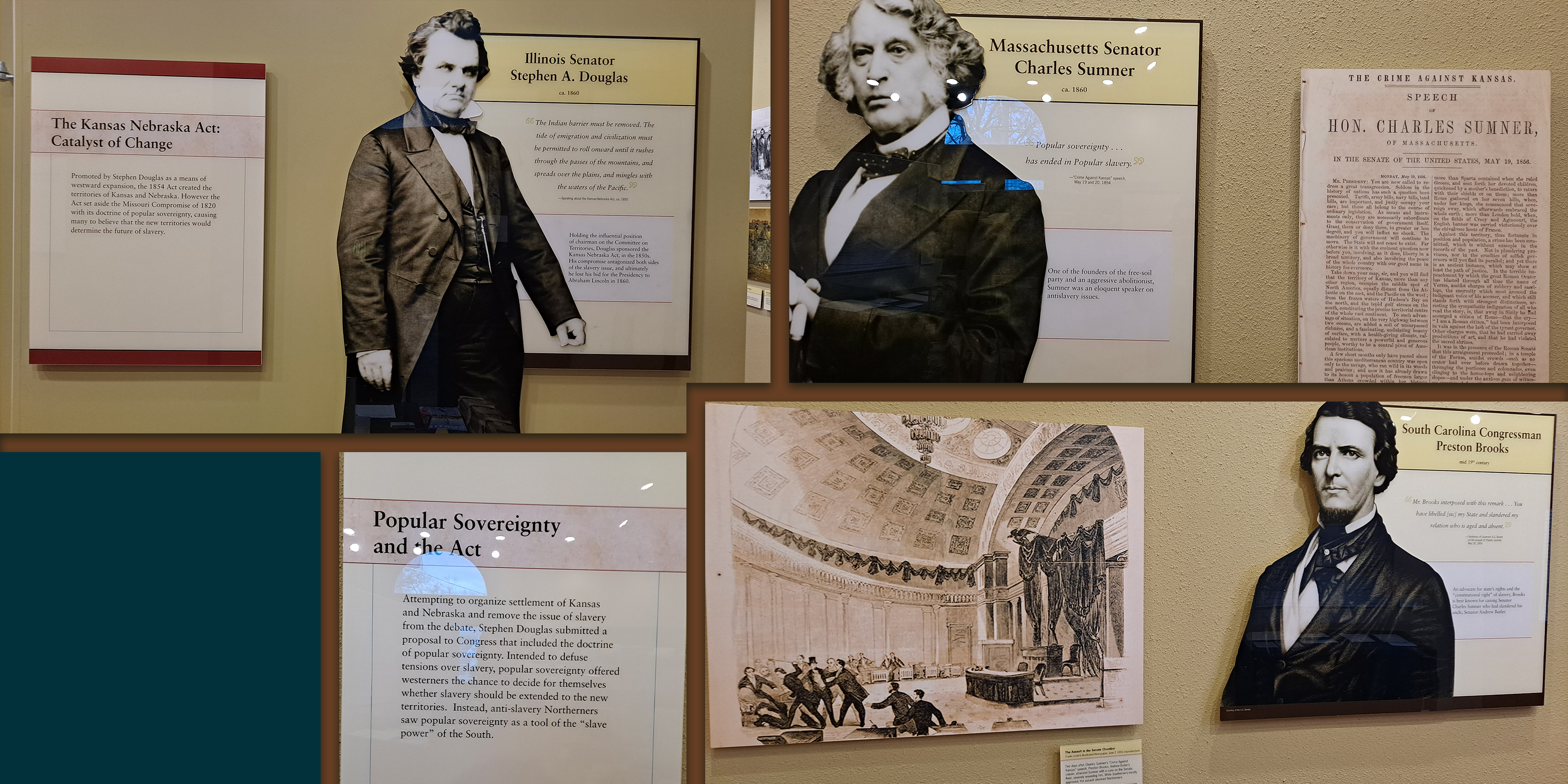

THE KANSAS-NEBRASKA ACT

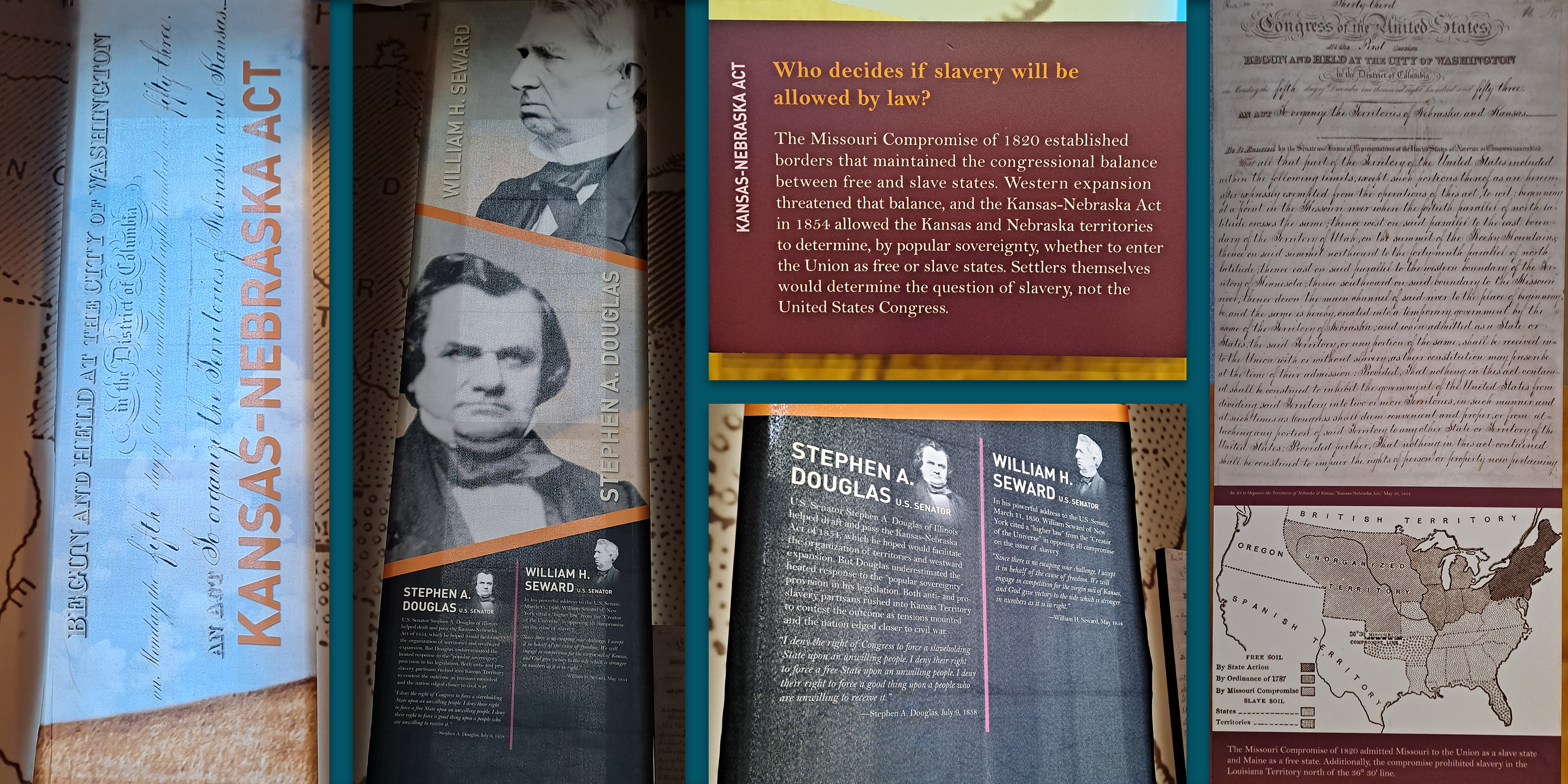

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 established borders that maintained the congressional balance between free and slave states. By the 1850s, Western expansion was threatening that delicate balance.

Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas sponsored the Kansas-Nebraska Act to help facilitate organizing the territories into states. The 1854 act allowed the Kansas and Nebraska territories to determine if they would enter the Union as free or slave states through popular sovereignty(def). Thus, local settlers themselves would determine the question of slavery, not the United States Congress. But Douglas underestimated the heated response to that provision. Both anti- and pro-slavery partisans(def) rushed to Kansas Territory to participate in these votes, which edged the nation closer to civil war.

The Missouri Compromise admitted Missouri to the Union as a “slave state” and Maine as a “free state.” Additionally, it prohibited expanding slavery in the Louisiana Territory north of the 36° 30’ line of latitude, which comprises most of Missouri’s southern border.

Stop 6

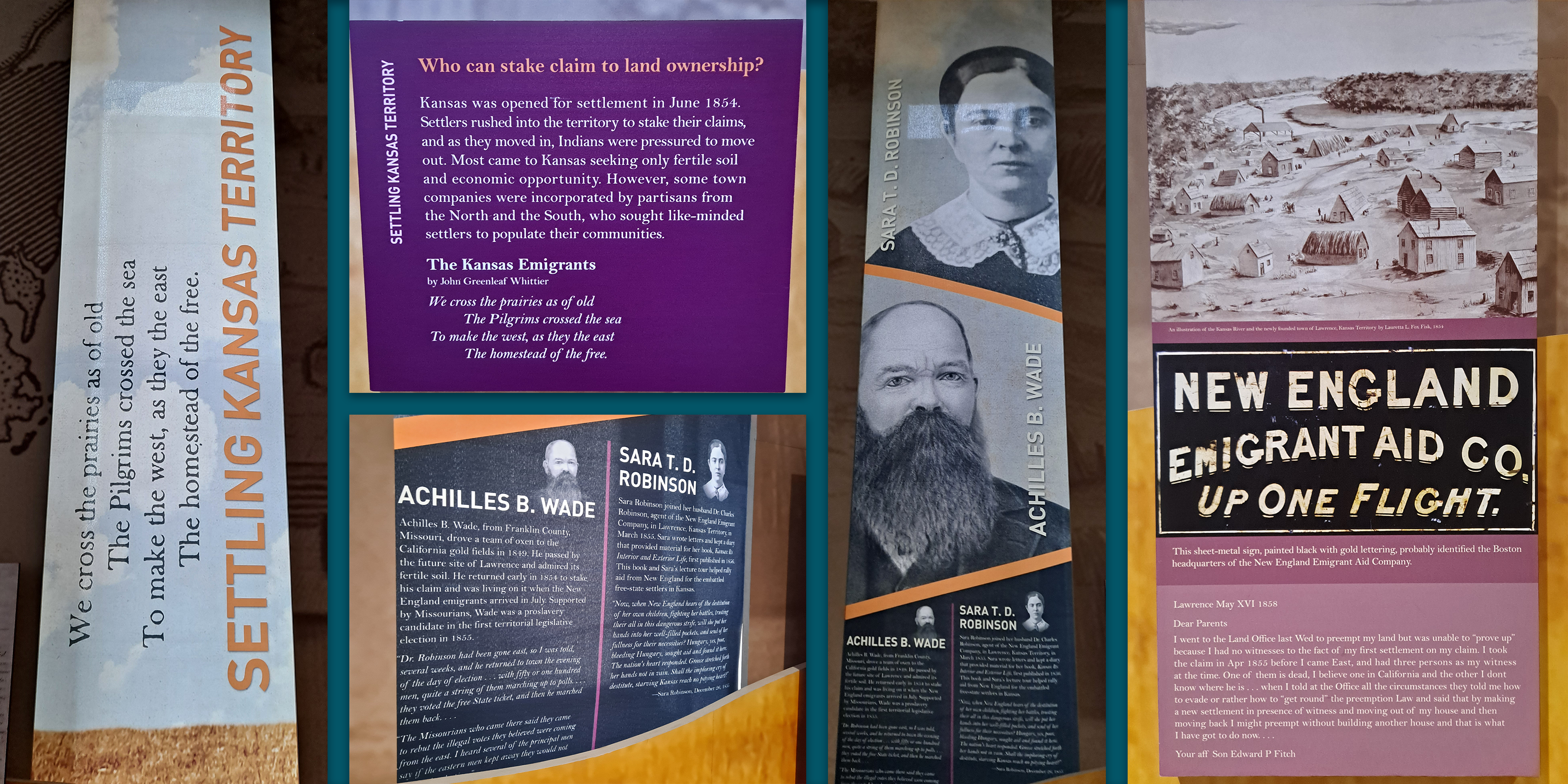

SETTLING KANSAS TERRITORY

SETTLING KANSAS TERRITORY

Achilles B. Wade, from Franklin County, Missouri, drove a team of oxen to the California gold fields in 1849. He admired the future site of Lawrence and returned to stake his claim in 1854. Angered by anti-slavery New England emigrants arriving in July, Wade became a pro-slavery candidate in the first territorial election in 1855. He was supported by neighboring Missourians, and furor over election schemes by the rival factions would quickly become evident. The following writings highlight the increasingly obvious potential for misconduct:

Dr. Robinson had been gone East, so I was told, several weeks, and he returned to town the evening of the day of the election… with fifty or one hundred men, quite a string of them marching up to the polls… they voted the free state ticket, and then he marched them back… The Missourians who came there said they came to rebut the illegal votes that they believed were coming from the east. I heard several of the principal men say if eastern men kept away they would not molest the election.’

--A.B. Wade, June 9, 1856.

Dr. Robinson had been gone East, so I was told, several weeks, and he returned to town the evening of the day of the election… with fifty or one hundred men, quite a string of them marching up to the polls… they voted the free state ticket, and then he marched them back… The Missourians who came there said they came to rebut the illegal votes that they believed were coming from the east. I heard several of the principal men say if eastern men kept away they would not molest the election.’

--A.B. Wade, June 9, 1856.

Dear Parents

I went to the Land Office last Wed to preempt my land but was unable to “prove up” because I had no witnesses to the fact of my first settlement on my claim. I took the claim in Apr 1855 before I came East and had three persons as my witness at the time. One of them is dead, I believe one in California and the other I don’t know where he is . . . when I told at the Office all the circumstances they told me how to evade or rather how to “get round” the preemption Law and said that by making a new settlement in presence of a witness and moving out of my house and then moving back I might preempt without building another house and that is what I have got to do now. . . .

Your aff Son Edward P Fitch, Lawrence May XVI 1858

I went to the Land Office last Wed to preempt my land but was unable to “prove up” because I had no witnesses to the fact of my first settlement on my claim. I took the claim in Apr 1855 before I came East and had three persons as my witness at the time. One of them is dead, I believe one in California and the other I don’t know where he is . . . when I told at the Office all the circumstances they told me how to evade or rather how to “get round” the preemption Law and said that by making a new settlement in presence of a witness and moving out of my house and then moving back I might preempt without building another house and that is what I have got to do now. . . .

Your aff Son Edward P Fitch, Lawrence May XVI 1858

Sara Robinson joined her husband Dr. Charles Robinson, an agent of the New England Emigrant Company, in Lawrence, Kansas Territory in March 1855. Her letters and diary were turned into the 1856 book, Kansas: Its Interior and Exterior Life. Sara’s book and lecture tour helped rally more aid from New England for the embattled free-state settlers in Kansas.

Stop 7

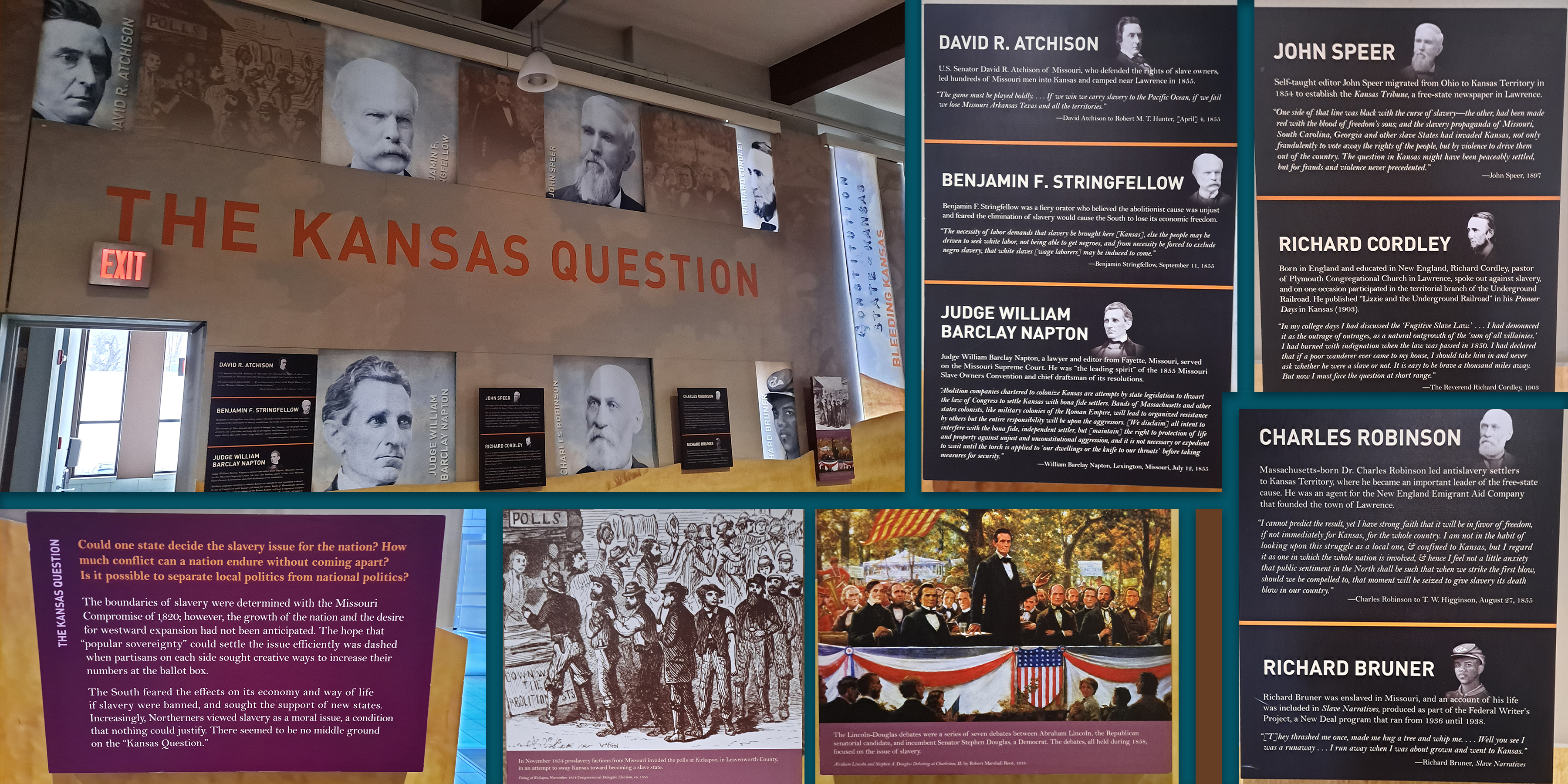

THE KANSAS QUESTION

THE KANSAS QUESTION

The boundaries of slavery determined in 1820 by the Missouri Compromise collapsed under unanticipated growth and expansion. The hope that “popular sovereignty” could prevail was dashed as each side tried to relocate citizens to create a majority during local elections. At issue were Southern fears of economic and social change if slavery was banned, while Northerners believed no moral justification could continue supporting the practice. There would be no middle ground.

Stop 8

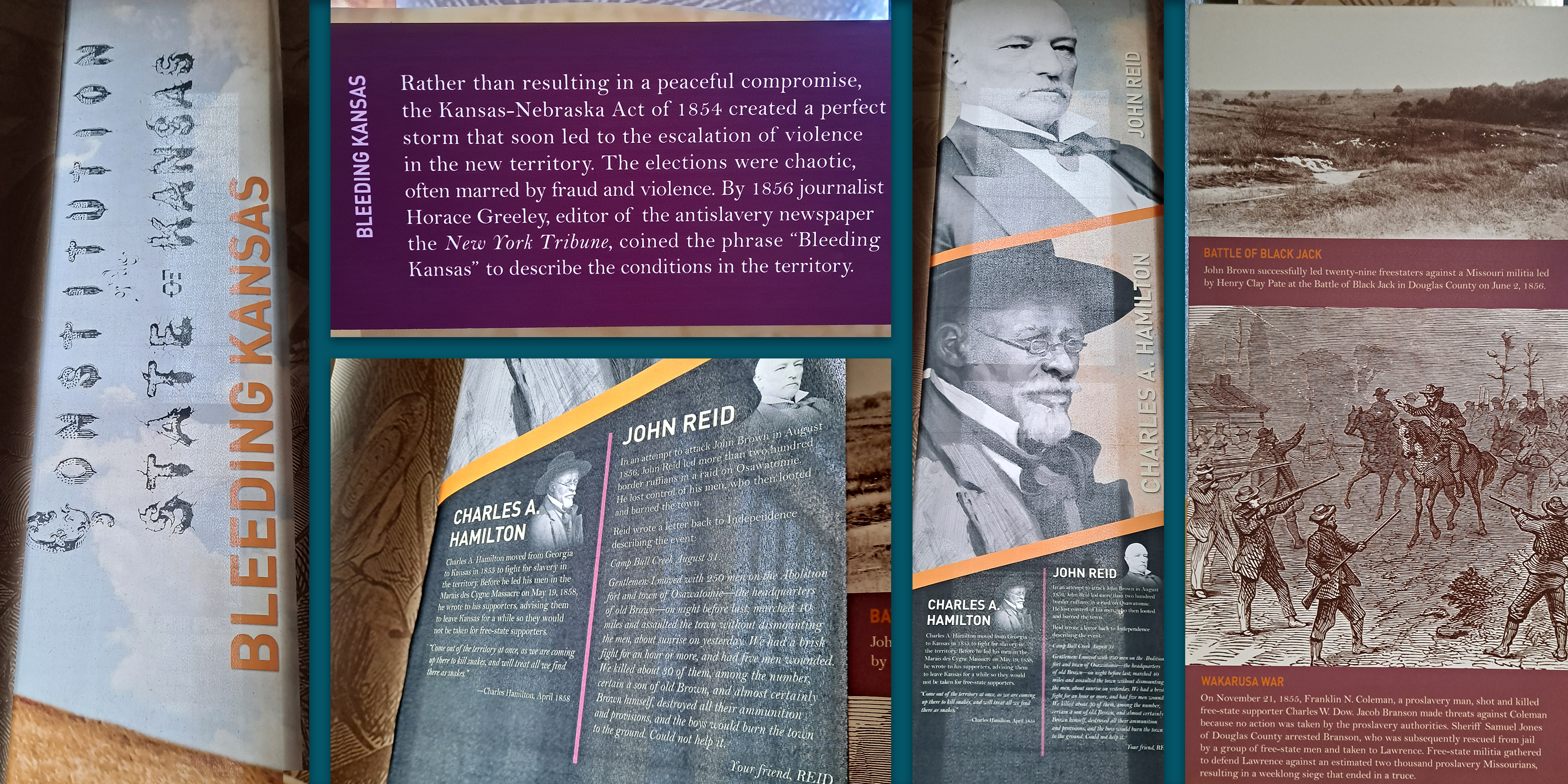

BLEEDING KANSAS

BLEEDING KANSAS

Instead of creating a peaceful compromise, the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 just escalated violence in the new territory. (sentence removed) By 1856 journalist Horace Greeley, editor of the antislavery newspaper New York Tribune, coined the phrase “Bleeding Kansas” to describe the conditions in the territory.

John Reid attempted to attack abolitionist leader John Brown, leading several hundred Border Ruffians in a raid on Osawatomie KS in 1856. Reid’s uncontrolled men pillaged the town and set it afire. In a letter sent back to Independence, MO he describes the raid:

"Camp Bull Creek August 31. Gentlemen: I moved with 250 men on the Abolition fort and town of Osawatomie—the headquarters of old Brown—on night before last; marched 40 miles and assaulted the town without dismounting the men, about sunrise on yesterday. We had a brisk fight for an hour or more, and had five men wounded. We killed about 30 of them, among the number, certain a son of old Brown, and almost certainly Brown himself, destroyed all their ammunition and provisions, and the boys would burn the town to the ground. Could not help it.

Your friend, REID.”

"Camp Bull Creek August 31. Gentlemen: I moved with 250 men on the Abolition fort and town of Osawatomie—the headquarters of old Brown—on night before last; marched 40 miles and assaulted the town without dismounting the men, about sunrise on yesterday. We had a brisk fight for an hour or more, and had five men wounded. We killed about 30 of them, among the number, certain a son of old Brown, and almost certainly Brown himself, destroyed all their ammunition and provisions, and the boys would burn the town to the ground. Could not help it.

Your friend, REID.”

Stop 9

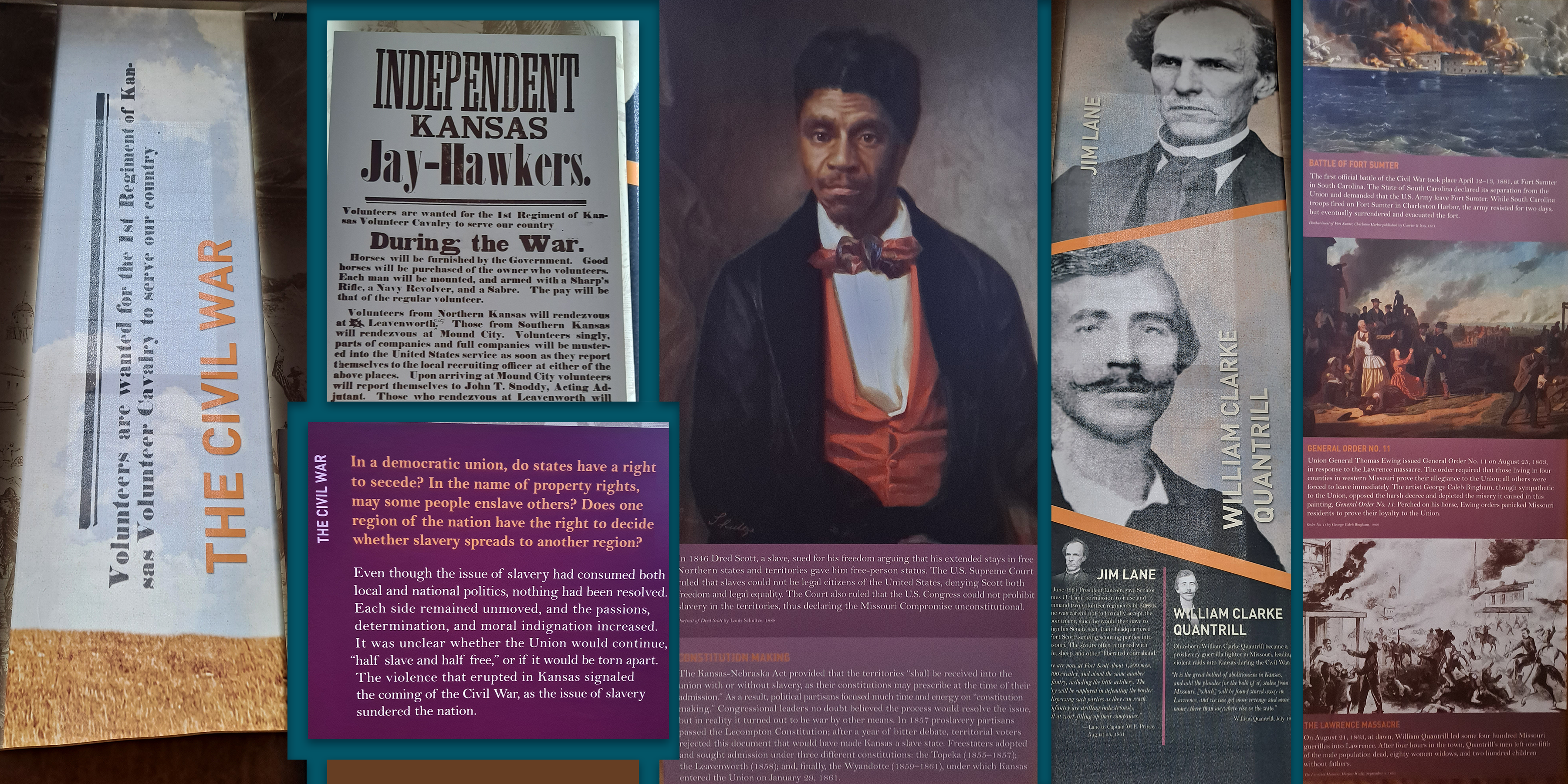

THE CIVIL WAR

THE CIVIL WAR

Each side remained stubbornly entrenched at both the national and local levels. Passion, determination, and moral indignation escalated, and it was increasingly unclear whether the Union could continue "half slave and half free.” As the issue of slavery split the nation, the violence that erupted in Kansas signaled the coming Civil War.

Stop 10

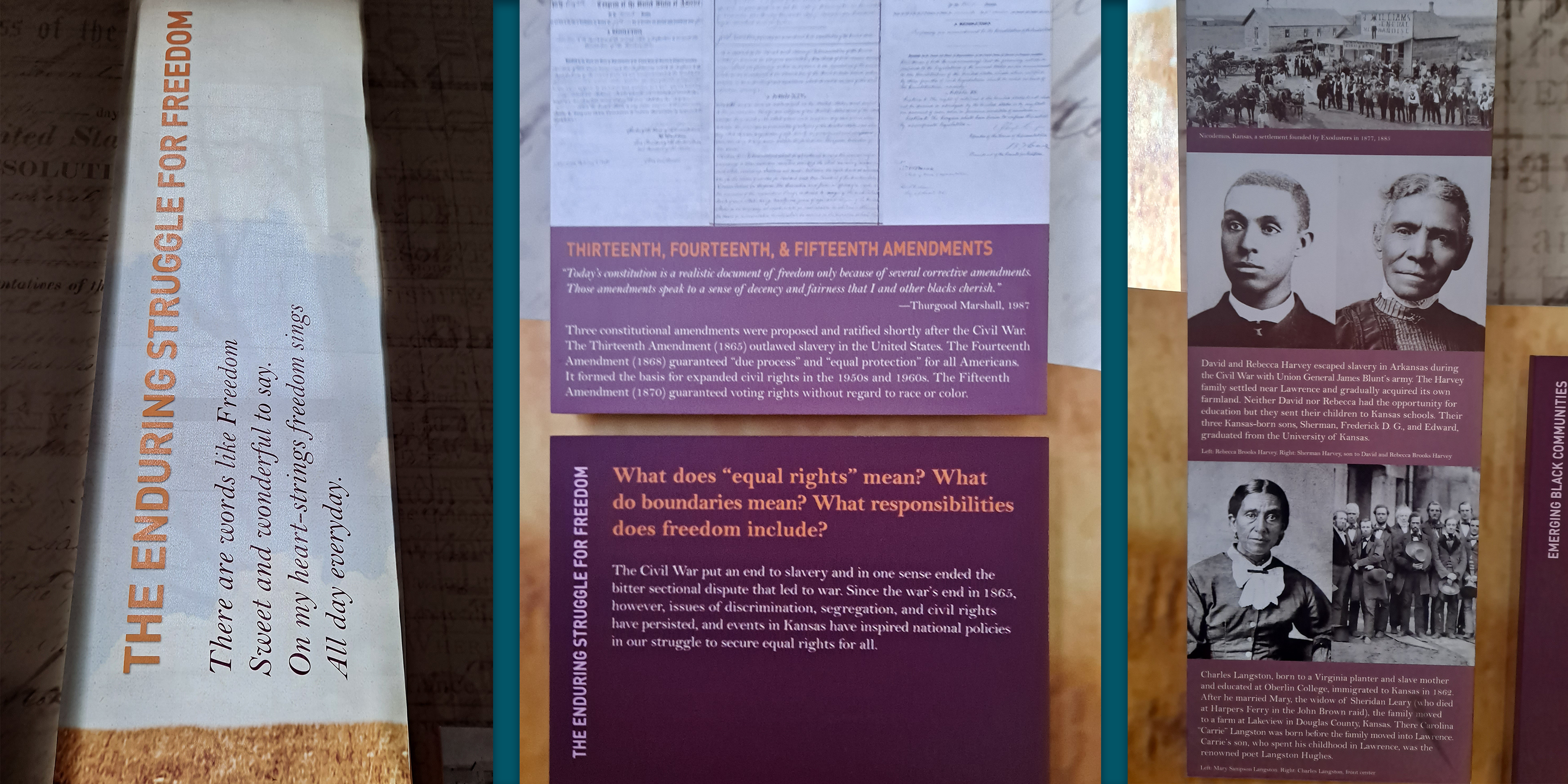

THE ENDURING STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM

THE ENDURING STRUGGLE FOR FREEDOM

The Civil War put an end to slavery in America and, in one sense, ended the bitter sectional dispute that led to war. Since 1865, however, issues of discrimination, segregation, and civil rights have persisted. Events in Kansas have continued to inspire national policies in our struggle to secure equal rights for all.

Stop 11

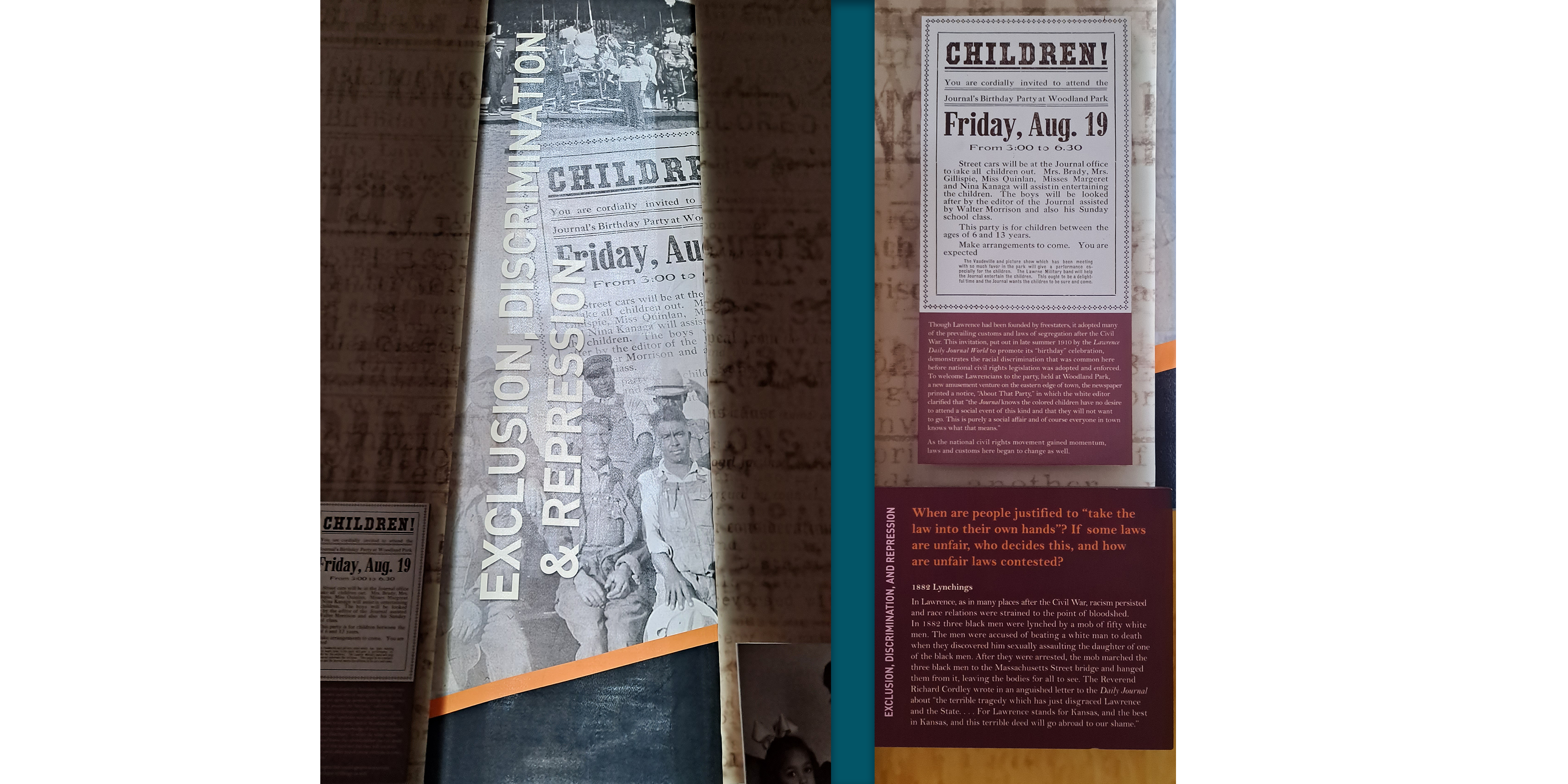

EMERGING BLACK COMMUNITIES: EXCLUSION, DISCRIMINATION, & DEPRESSION

EMERGING BLACK COMMUNITIES: EXCLUSION, DISCRIMINATION, & DEPRESSION

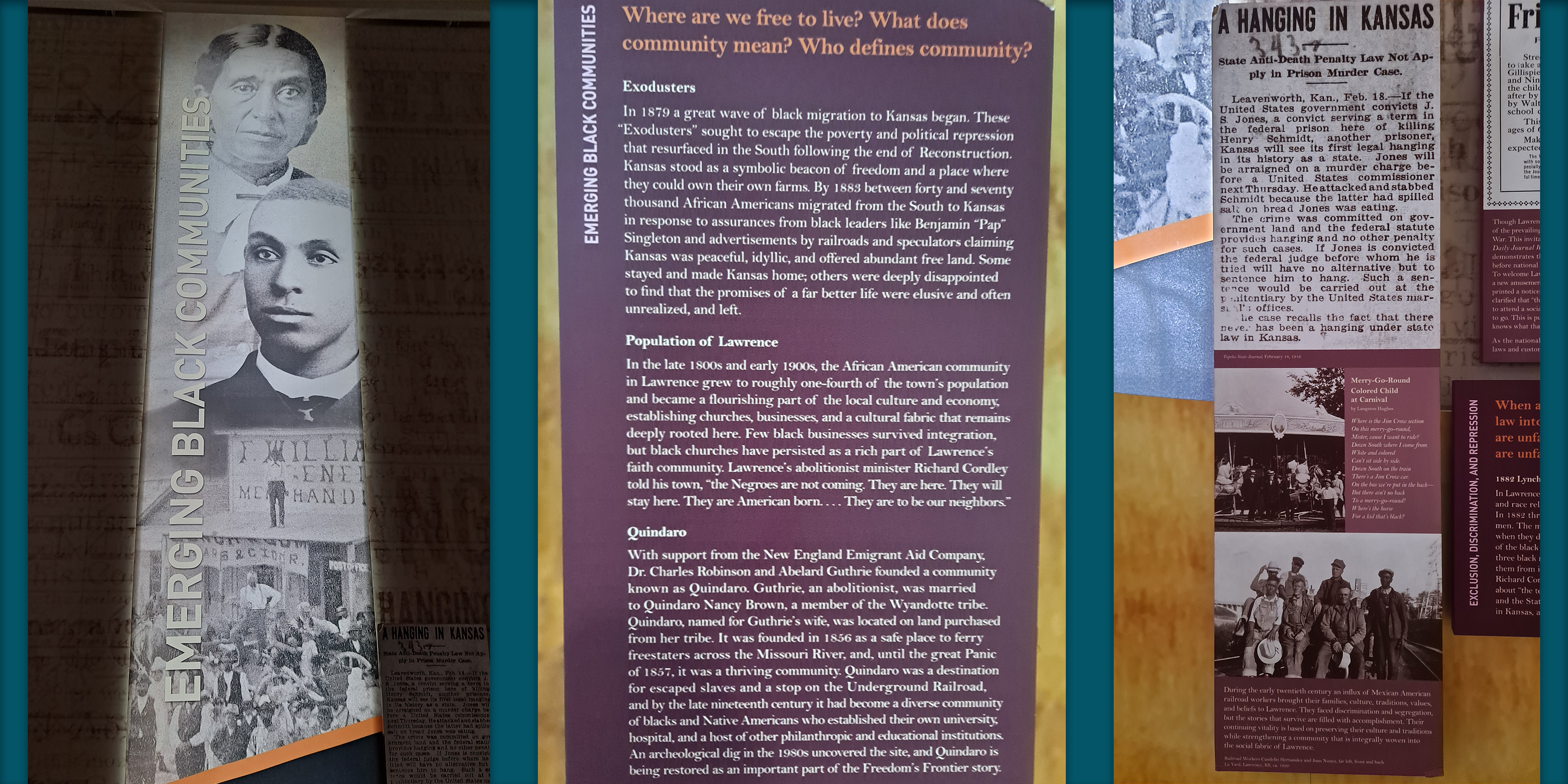

Exodusters:

A great wave of Black migration westward began in 1879. These "Exodusters" sought to escape the poverty and political repression that resurfaced in the South following the end of the period known as Reconstruction. Kansas stood as a symbolic beacon of freedom and land ownership. By 1883, between forty and seventy thousand African Americans migrated from the South to Kansas. They were encouraged by Black leaders like Benjamin “Pap” Singleton as well as advertisements by railroads and speculators claiming Kansas was a peaceful paradise. Some stayed and made Kansas home; others returned deeply disappointed to find that the promises of a better life were elusive or unrealized.

A great wave of Black migration westward began in 1879. These "Exodusters" sought to escape the poverty and political repression that resurfaced in the South following the end of the period known as Reconstruction. Kansas stood as a symbolic beacon of freedom and land ownership. By 1883, between forty and seventy thousand African Americans migrated from the South to Kansas. They were encouraged by Black leaders like Benjamin “Pap” Singleton as well as advertisements by railroads and speculators claiming Kansas was a peaceful paradise. Some stayed and made Kansas home; others returned deeply disappointed to find that the promises of a better life were elusive or unrealized.

Population of Lawrence:

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Lawrence’s African-American numbers grew to roughly a quarter of the town’s population and became a flourishing part of the local culture and economy. Black leaders established churches, businesses, and a cultural fabric that remains deeply rooted there. While few Black businesses survived integration, Black churches persisted as a rich part of Lawrence's faith community. At the turn of the 20th century, White Lawrence abolitionist minister Richard Cordley reportedly told his town, “The Negroes are not coming. They are here. They will stay here. They are American born… They are to be our neighbors.”

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Lawrence’s African-American numbers grew to roughly a quarter of the town’s population and became a flourishing part of the local culture and economy. Black leaders established churches, businesses, and a cultural fabric that remains deeply rooted there. While few Black businesses survived integration, Black churches persisted as a rich part of Lawrence's faith community. At the turn of the 20th century, White Lawrence abolitionist minister Richard Cordley reportedly told his town, “The Negroes are not coming. They are here. They will stay here. They are American born… They are to be our neighbors.”

Quindaro:

With support from the New England Emigrant Aid Company, abolitionists Dr. Charles Robinson and Abelard Guthrie founded this community. Guthrie married a local member of the Wyandotte tribe named Quindaro Nancy Brown. The town of Quindaro, founded in 1856 and named for Guthrie’s wife, was located on land purchased from her tribe. The thriving community was a safe place to ferry free-staters across the Missouri River until the financial Panic of 1857(def). Quindaro had also been a destination for escaping slavery as a stop on the Underground Railroad. By the late nineteenth century, it had become a diverse community of Blacks and Indigenous Americans who established their own university, hospital, and a host of other philanthropic and educational institutions. An archeological dig in the 1980s uncovered the site, and Quindaro is being restored as an important part of the Freedom's Frontier story.

With support from the New England Emigrant Aid Company, abolitionists Dr. Charles Robinson and Abelard Guthrie founded this community. Guthrie married a local member of the Wyandotte tribe named Quindaro Nancy Brown. The town of Quindaro, founded in 1856 and named for Guthrie’s wife, was located on land purchased from her tribe. The thriving community was a safe place to ferry free-staters across the Missouri River until the financial Panic of 1857(def). Quindaro had also been a destination for escaping slavery as a stop on the Underground Railroad. By the late nineteenth century, it had become a diverse community of Blacks and Indigenous Americans who established their own university, hospital, and a host of other philanthropic and educational institutions. An archeological dig in the 1980s uncovered the site, and Quindaro is being restored as an important part of the Freedom's Frontier story.

Stop 12

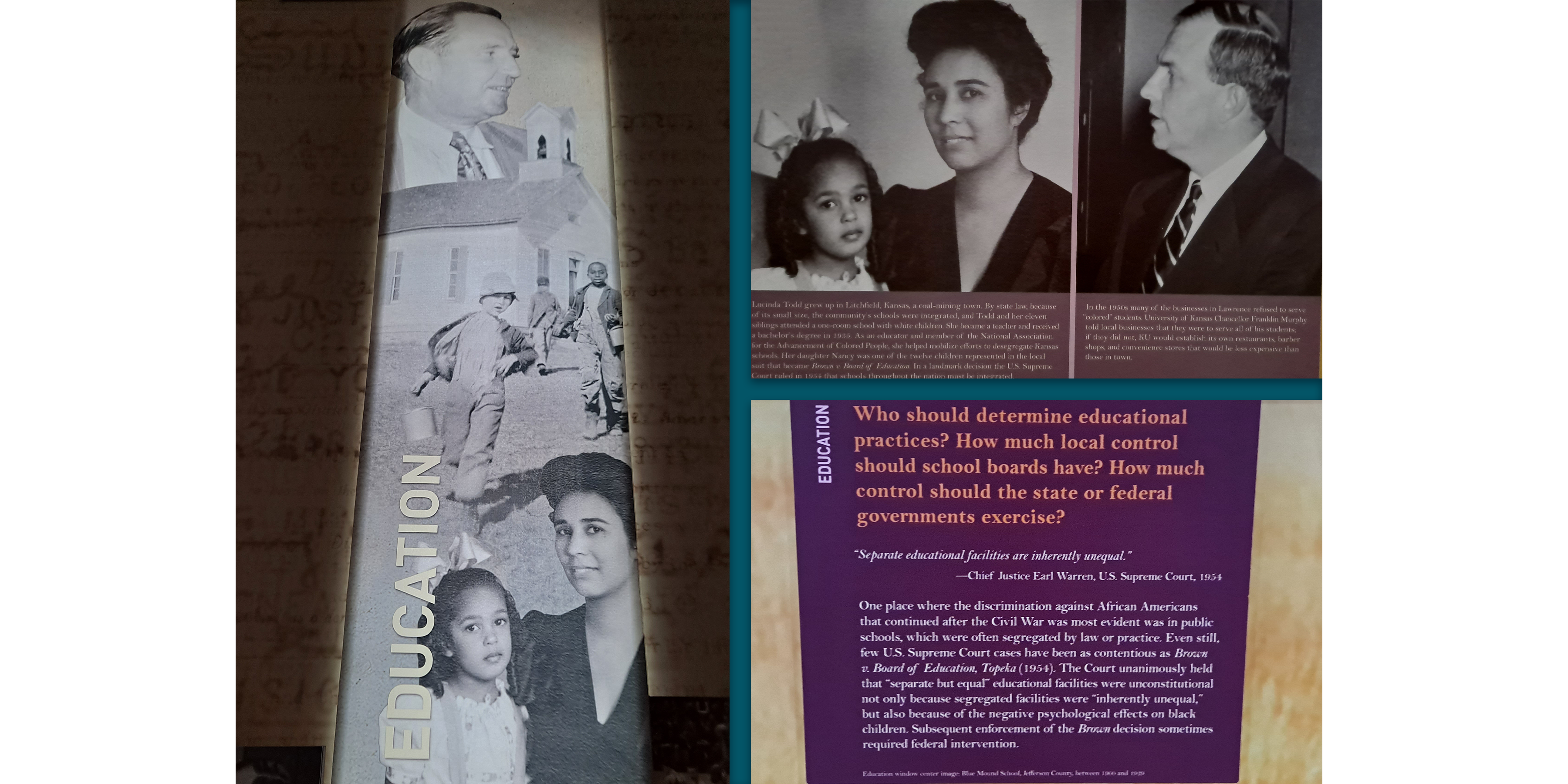

EDUCATION

EDUCATION

"Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

—Chief Justice Earl Warren, U.S. Supreme Court, 1954

—Chief Justice Earl Warren, U.S. Supreme Court, 1954

Discrimination that continued after the Civil War against Blacks was most evident in public schools, which were often segregated by law or practice. Few U.S. Supreme Court cases have been as contentious as Brown v. Board of Education, Topeka (1954) when the justices unanimously held that “separate but equal” public school facilities were unconstitutional. This was not only because segregated facilities were “inherently unequal,” but also because of the negative psychological effects on Black children. Subsequent enforcement of the Brown decision, however, sometimes required federal and/or military intervention.

Stop 13

CIVIL RIGHTS

CIVIL RIGHTS

Wilt Chamberlain:

The famous 7-foot-1-inch basketball star from Philadelphia arrived at KU in 1955, and was shocked to find “the whole area around Lawrence… was infested with segregation.” In response, Chamberlain made a practice of visiting segregated restaurants around town, sitting there until he received service. He was supported by his coach, Forrest C. “Phog” Allen, who insisted all Massachusetts Street businesses serve him.

The famous 7-foot-1-inch basketball star from Philadelphia arrived at KU in 1955, and was shocked to find “the whole area around Lawrence… was infested with segregation.” In response, Chamberlain made a practice of visiting segregated restaurants around town, sitting there until he received service. He was supported by his coach, Forrest C. “Phog” Allen, who insisted all Massachusetts Street businesses serve him.

Harry S. Truman:

From our early history, African Americans were distinguished members of segregated armed forces. Over time, they have been the U.S. “Colored” Troops during the Civil War; known as “Buffalo Soldiers,” a cavalry unit formed in 1866 at Fort Leavenworth; and served as “Tuskegee Airmen,” who served as fighter pilots in WWII. Blacks returned from defending democracy in both WWI and WWII to face continued discrimination and racial violence. President Harry Truman of Independence, Missouri, ultimately issued Executive Order 9981 in July 1948, abolished segregation in the armed forces, and required equal opportunity and treatment for all military personnel. With careful planning, the armed forces integrated without a major incident over the next three years.

From our early history, African Americans were distinguished members of segregated armed forces. Over time, they have been the U.S. “Colored” Troops during the Civil War; known as “Buffalo Soldiers,” a cavalry unit formed in 1866 at Fort Leavenworth; and served as “Tuskegee Airmen,” who served as fighter pilots in WWII. Blacks returned from defending democracy in both WWI and WWII to face continued discrimination and racial violence. President Harry Truman of Independence, Missouri, ultimately issued Executive Order 9981 in July 1948, abolished segregation in the armed forces, and required equal opportunity and treatment for all military personnel. With careful planning, the armed forces integrated without a major incident over the next three years.

Stop 14

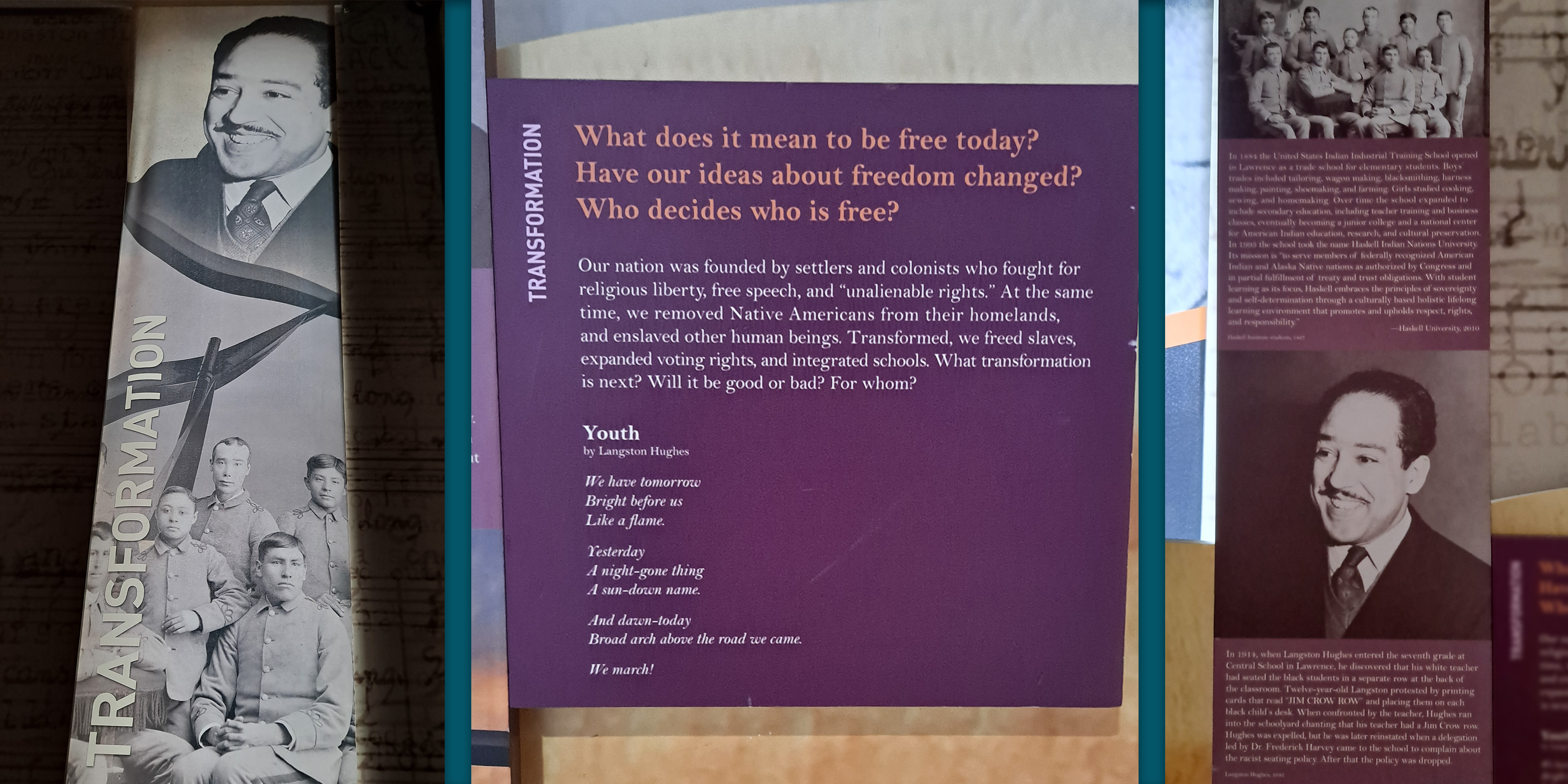

TRANSFORMATION

TRANSFORMATION

Our nation was founded by settlers and colonists who fought for religious liberty, free speech, and “unalienable rights.” Historically though, Americans removed Native Americans from their homelands and enslaved other human beings. Transformed, we freed slaves, expanded voting rights, and integrated schools. What transformation is next? Will it be good or bad? For whom?

Stop 15

EAST GALLERY

EAST GALLERY

Now, complete your tour by visiting the smaller East Gallery. In this “Kansas-Nebraska” room, you will find artifacts and other content which add context to the struggle for freedom you read about here. From the Kansas-Nebraska Act, known as the catalyst for “Bleeding Kansas,” up to the ratification of both Kansas and Nebraska as free states, this part of our nation reminds us that the extent of freedom is in the hands of the people.

FREEDOM'S FRONTIER NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

1047 MASSACHUSETTS ST

LAWRENCE, KS 66044

785.856.5300

SIGN UP FOR THE MONDAY MINUTE

Read the latest news about Freedom's Frontier and its partners every week.

SIGN UP FOR HISTORY HAPPENS

Stay up to date on events in the heritage area with this biweekly newsletter.