KANSAS CITY, KANSAS

AFRICAN-AMERICAN LEGACY TOUR

Use this arrow to learn more at each stop.

This tour is based on research provided by America Patton under a grant from Visit Kansas City Kansas.

Celebrating the African-American experience in Kansas City, Kansas, this self-guided tour highlights 19 notable locations throughout the area's rich history.

Scroll down to continue the tour.

Previous slide

Next slide

Birthplace of Bird Parker

852 Freeman Ave. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS852 Freeman Ave. Kansas City, KS

Charlie Parker (1920 – 1955), was born in KCK and lived there until 1927. Parker moved to New York where he pioneered bebop, a revolution in jazz. Parker was, without doubt, a true musical genius. Parker attended Douglass Elementary School, and following his family’s move to Kansas City, Missouri, he attended Lincoln High School (African American History (Northeast Area). Bursting with fresh ideas and virtuosity, his solos and compositions have inspired musicians and composers across a broad spectrum of music, ranging from Moondog, a contemporary composer and street musician, to the rock group the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Jazz historian Martin Williams judged that Charlie included “everyone.” In 1965, jazz pianist Lennie Tristan observed, “If Charlie Parker wanted to invoke plagiarism laws, he could sue almost everybody who’s made a record in the last ten years.” (1)

Charlie’s brilliance and charisma also inspired dancers, poets, writers, filmmakers, and visual artists. Jack Kerouac emulated Charlie’s improvisational style in his poem “Mexico City Blues,” writing, “I want to be considered a jazz poet blowing a long blues in an afternoon jazz jam session on Sunday.” Kerouac’s novel, The Subterraneans features a cameo appearance by Charlie. Waring Cuney, Robert Pinsky, Robert Creely, and numerous other poets have also sung Charlie’s praises in verse. Clint Eastwood paid homage to Charlie’s tortured genius with his film Bird. In 1984, the Alvin Ailey Dance Company celebrated Parker. Artist Jean Michel Basquiat honored Charlie with many artworks, including Charles the First. (2)

Parker began playing alto and baritone horn in high school before switching to alto saxophone. His talents were not immediately evident, he was once laughed off the bandstand at a jam session for playing in the wrong key. He began practicing zealously, and soon came under the tutelage of saxophonist Buster Smith, who was an important influence on Parker’s early musical development. While in New York in 1938, Parker worked as a dishwasher at a restaurant to hear its musical act, pianist Art Tatum. Parker made his earliest recordings with Jay McShann’s band in 1940 and 1941. He later joined Earl Hines’ band, where he first worked with trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, and both played with the important band at New York’s Three Deuces club, and Parker started recording for the Savoy label. Shortly after, the band traveled to Los Angeles, introducing bebop to West Coach audiences. Parker remained there, making a number of recordings for the Dial label. (3)

Parkers' musical genius makes a significant impact on every indigenous culture around the world. Parker’s musical excellence, originality, and innovation set him apart, defining the future of jazz and spawning legions of imitators on every instrument. Today, Parker’s music, original compositions, records, and musical scores can be found in diverse schools, universities, libraries, and music stores around the globe. The musical library that he left behind continues to create harmony, balance, and unity around the globe. Equally important, his music, and his faith to create, innovate, and explore new ideas continues to bring hope to new novice musicians, seasoned musicians, jazz students, and music listeners in general. Charlie “Bird” Parker fulfilled his musical calling, and because of Parker, the future of jazz will continue to sustain through the next generation of learners, and listeners. Additional information about Charlie “Bird” Parker can be located inside of the American Jazz Museum on 18th and Vine in Kansas City, Missouri.

Previous slide

Next slide

Civil War Granite Monument

2062 N 9th St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS2062 N 9th St. Kansas City, KS

The main inscription reads: "Erected In ~ Memory Of The ~ Known And Unknown ~ Colored Soldiers And ~ Sailors Who ~ Fought In Defense Of ~ The Union From ~ 1861 - 1865 ~ By Sumner Relief ~ Corps No 22 ~ Through The Special ~ Efforts Of The ~National Aides ~ line obliterated ~ Cora S. Dameron". Marker dedicated Memorial Day 1905 by the Sumner Relief Corps Post No. 22, W.R.C.

Previous slide

Next slide

Colored Masons of KC

214 C St. Washington, KS

DIRECTIONS214 C St. Washington, KS

Segregated Masons organization. In 1854, three Wyandot Indians and five white settlers, all of whom were Mason, coalesced in what is now Wyandotte County, Kansas, and petitioned the Grand Lodge of Missouri to establish a Lodge of Masons in a Wyandot Indian Village. On August 4th, 1854, the dispensation was granted, and one week later Kansas Lodge U.D. (eventually to become Wyandotte Lodge No. 3) opened for work. Within two years, two other lodges in Kansas were formed, and in 1856 the trio formed the Grand Lodge of Kansas as the American Civil War loomed (4). The Osborn Guards paraded in public for the first time on August 18th, 1875, when the unit joined a Kansas Avenue procession celebrating “the establishment of the Royal Arch degree among the colored Masons of Kansas (5).

There were at least six African American social societies operating in Kansas City, Kansas by the turn of the century. The Prince Hall Masons, established in 1875 and Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, established shortly after, were the earliest groups. In 1886, these two groups joined forces to build the Mason and Odd Fellow Hall at 8th and Washington. The two-story building was built by an all-African American crew. The first floor had an auditorium, while the second floor was divided into meeting rooms. Several Masonic Lodges met in this hall, and it was used by the “First AME Church in 1887 and the 8th Street Baptist Church after a fire in 1917. St. James Masonic Lodge Masonic Lodge in Quindaro and St. Andrews in the Bottoms, and also served the African American community (6).

Previous slide

Next slide

Note: Approximate location of DeAngelo's Restaurant.

DeAngelo's Restaurant & Kresge's Department Store Sit-Ins

NE Corner of Minnesota Ave. & 7th St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONSNE Corner of Minnesota Ave. & 7th St. Kansas City, KS

From 1960 - 1963, Civil Rights activity continued to occur in Kansas City, Kansas. Desegregation in employment and public accommodations, especially on Minnesota Avenue, occurred because of public protest. The initial protest during this period was a sit-in at DeAngelo’s restaurant. Kresge’s Department Store on Minnesota Ave. is another location where sit-ins occurred in the year of 1952. Kansas City, Kansas is listed as one of the cities that had a sit-in before the one in Greensboro, North Carolina. February 5th, 1960, had become known as the opening of the sit-in movement. Civil rights activists, however, had conducted sit-ins between 1957 and 1960 in at least sixteen cities: St. Louis, Missouri, Wichita, Kansas, Kansas City, Kansas, and Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. (7). In the years prior to these sit-ins on Minnesota Ave, Civil Rights demonstrations took place in the courts, in the streets, through musical expression, in schools, libraries, churches, parks, museums, in music venues, through diverse literature, and through cultural storytelling. (8)

Previous slide

Next slide

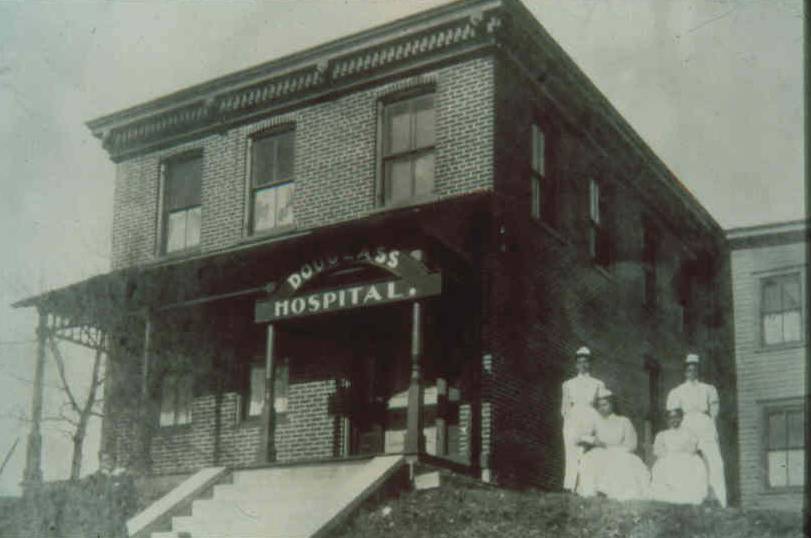

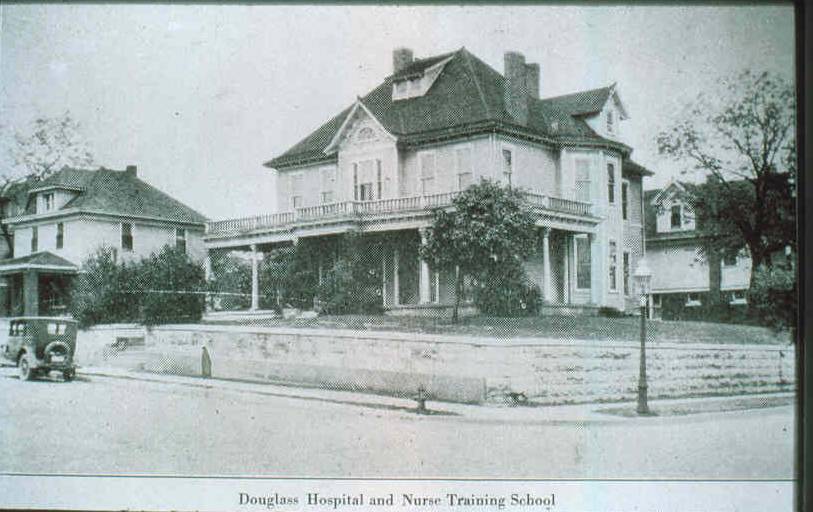

Douglas Hospital

3500 N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS3500 N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

Dr. S.H. Thompson Sr. graduated from Howard University Medical School in 1892 and moved to Kansas City, Kansas the same year. Upon his arrival, he became the third African American doctor in the city. He started his practice as a horse and buggy doctor making house calls for surgery and general practice. He later had an office in the Wyandotte Drug Company, along with several other medical professionals. A separate hospital was needed, because black doctors were not permitted to perform surgery in existing hospitals. In response to the need, Thompson joined forces with I.F. Bradley, a lawyer and elected official. I.F. Bradley Sr. graduated from Kansas University Law School with honors in 1887. He moved to Kansas City, Kansas and he established a law office at 518 Minnesota Ave. He was elected to the justice for the peace in 1889 and played a lead role in local politics and civic affairs until his death in 1938.

He was a charter member of the National Afro-American Council and the Niagara Movement. I.F. Bradley and Dr. Thompson partnered in the founding of Douglas Hospital and at least three other cooperative business enterprises. In 1899, “Douglas Hospital and Training School for Nurses” opened in a two-story brick building at 312 Washington Blvd. The hospital was named in honor of Reverend Calvin Douglas of Western University. The hospital provided care regardless of the patient's ability to pay. This charitable aid was provided thanks to many community organizations, including the Douglas Relief Union. In 1905, the hospital became formally sponsored by the AME Church with Reverend Abraham Grant as a leading supporter. In 1915 the nursing school became affiliated with Western University (9).

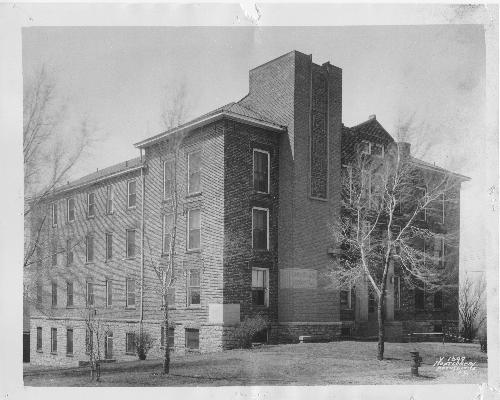

Following the demise of Western University, the segregated Douglass Hospital occupied the remodeled Grant Hall in 1945. Douglass nursing school had been affiliated with Western University since the early 1900’s. One by one, the buildings on the Western campus were demolished, to be replaced in the 1960s by an institution that was affiliated with Douglass Hospital”. Primrose Villa elderly housing where Ward Hall and Park Hall had stood, and Bryant - Butler - Kitchen nursing home on the site of Stanley Hall and the State Industrial Department. Hancks explains in the “Quindaro and Western University Historic District”, that Douglass Hospital closed in 1978, an ironic victim of integration, and possibly too, because of frictions between the church, community, and state. Some historical sources mention that Douglas Hospital operated until 1977 (10), (11).

Previous slide

Next slide

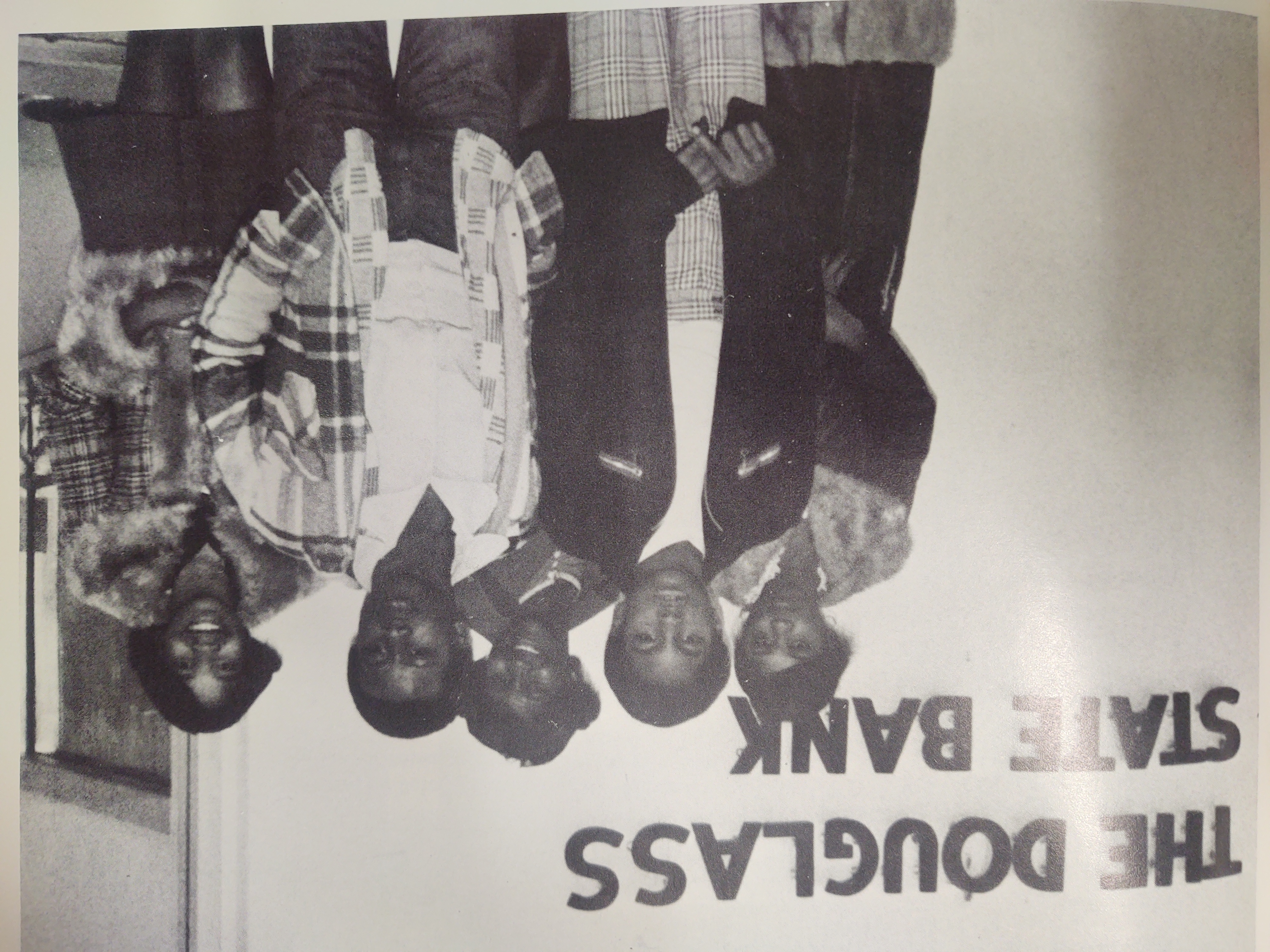

Douglass State Bank

1314 N 5th St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS1314 N 5th St. Kansas City, KS

Douglas State Bank thrived economically and served African Americans during the era of segregation. The owner, H.W. Sewing was born on February 15, 1891 in Bremond, Texas. He came to Kansas City, Kansas in 1920. He worked as a laborer at two locations, taught mathematics and bookkeeping at Western University and was a salesman for two life insurance companies before becoming General Manager of the Kansas City office of Atlanta Life Insurance Company. The office became one of the most profitable branches of Atlanta Life in the country. While employed there, Sewing started the Sentinel Loan and Investment Company, which was very successful. The charter for the approval of Douglass State Bank was approved in September 1946 and issued in October 1946. The bank opened on August 25th, 1947.

Previous slide

Next slide

Gravesite of Junius Groves

SE Corner of Swartz Rd. & S 86 St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONSSE Corner of Swartz Rd. & S 86 St. Kansas City, KS

Grave of Groves’ son. While Groves is rumored to be buried here, his grave was either vandalized or purposefully obscured to deter potential vandals.

Grave of Groves’ son. While Groves is rumored to be buried here, his grave was either vandalized or purposefully obscured to deter potential vandals.

Grave of Groves’ son. While Groves is rumored to be buried here, his grave was either vandalized or purposefully obscured to deter potential vandals.

Grave of Groves’ son. While Groves is rumored to be buried here, his grave was either vandalized or purposefully obscured to deter potential vandals.

Groves came to Kansas City, Kansas from Louisville, Kentucky in 1879, He moved to a ten-acre farm near Edwardsville, Kansas. By the turn of the century, he owned in excess of 500 acres of farmland, and in 1902, his potato harvest exceeded that of any farmer on record in the world - thus earning for himself the title of “Potato King of the World.” Groves was a self-educated entrepreneur and the wealthiest African American in the US by the first decade of the 20th century. Groves was a founding member of the Kansas State Negro Business League, the Kaw Valley Potato Association, the Sunflower State Agricultural Association, and the Pleasant Hill Baptist Church Society. In the early 1900s, he founded the community of Groves Center near Edwardsville, selling small tracts of land to African American families. He also built a golf course for African Americans, possibly the first such course in the country (12). Although Groves was extremely wealthy, he was a servant at heart, he supported and mentored youth, he was a family man, a devoted husband, and he served as trustee for Western University in Quindaro, Kansas (13).

Previous slide

Next slide

John Brown Statue (Western University)

3440 N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS3440 N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

In 1911, Western University made national news when it erected the nation’s first statue of John Brown. Today, the statue of Brown still stands. Brown is holding a diploma, which symbolized the continuing fight for African American freedom through education. (14). John Brown dedicated himself to the struggle against slavery, which in the mid-1850’s, was being waged by arms in Kansas (15).

Anthony Hope, who was born in Douglass Hospital on November 8th 1961, and who is the current president of the Old Quindaro Museum, confirms that Mr. John Walker, who was a care-taker of Western University, was instrumental in helping to raise the funds to construct the John Brown statue. In addition to Hope’s story about Walker, local community historian, Mr. Luther Smith confirmed that Walker was the supervisor of the janitors, and the grounds-keeping crew of Western University. Smith mentioned that Walker was his uncle. Smith worked for 60 years at Western University. Smith remembers his uncle pushing a wheel-barrow around campus and the community with his dog. Over 2,000 dollars were raised for the construction of the John Brown statue. It was imported from Italy, and placed on the campus of Western University. The statue used to sit back further on campus than its current position. (16).

Previous slide

Next slide

Kansas Room Special Collections

625 Minnesota Ave. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS625 Minnesota Ave. Kansas City, KS

Kansas City, Kansas is a city rich in history. Lewis and Clark stopped near this area during their first expedition of the Louisiana Territory in 1804. The Wyandott Indians settled in what is now known as Kansas City, Kansas in 1843. Many African - Americans from the South known as the Exodusters, settled here in the late 1870s. The Kansas Room also holds special collections related to the history of Wyandots in Kansas, the Huron Cemetery, the history of the library and public schools.

Previous slide

Next slide

Northeast Jr. High School

400 Troup Ave. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS400 Troup Ave. Kansas City, KS

Northeast Jr. High School was organized in 1923 and was located on the site once owned by the fowler family of the fowler Packing Industry at Fourth Street and Troup Avenue. The building was not occupied until 1925. Grades seven, eight, and nine were located in this school. The Elementary schools with grades one through six and attended by Black students were the “feeder” school for Northeast Jr. High School. In addition to those feeder schools, Black families from White Church, Edwardsville, and Shawnee Mission, Kansas had to send their children to Northeast Junior High School. Students who lived in Rosedale, Argentine, Armourdale, and other outlying areas, were transported there by McCallop and Rucker Bus Service, two African American owned companies. Other students who lived too far to walk were given two bus tokens at the end of the school day; one to get home and one to return to school the following morning.

The first principal of Northeast Junior High School from 1923-1929, was J.P. King. The second principal of Northeast Junior High School was Joseph H. Collins, who served as principal for twenty-nine years, longer than any other person. The faculty at Northeast Junior were outstanding and dedicated during the years of its existence.

Northeast Jr. High School was the only Junior High School in Kansas City, Kansas that had a membership charter for the National Jr. Honor Society. Charter #31 was issued to the Northeast in 1931. Also, Northeast was the first Junior High School in the city to have a chapter in the Future Teachers of America, (F. T. A.). Rozella Caldwell Swisher sponsored this program. In 1938, a Hammond electric organ was purchased at the cost of $2,000 and became the only Junior High School with an organ in its auditorium. This organ was paid for by the citizens of the Northeast Community of Kansas City, Kansas.

The band at Northeast was always outstanding; Respected and prolific band director, Mr. Leon Brady taught there until he was transferred to Sumner High School. (17). The school was closed as a result of a mandate issued by the District Court in 1977.

Notable Educators

Gary Stevenson - the outstanding educator, bowler, servant, mentor, and man of faith began his teaching career at Northeast Junior High School. Stevenson was born in Kansas City, MO, but moved to Kansas City, KS where he taught Mathematics to diverse students. Stevenson was an honor student throughout college. Stevenson was known for motivating kids who needed hope, and for getting students who did not enjoy math, excited about learning math. Although Stevenson never had any kids through birth, he took in many kids who needed a caring role model. He often provided a warm meal to diverse families, and he saw the best in every student.

Stevenson was a gentle giant, a solid dresser, and a man who had a joyful spirit inside the classroom, in the community, and in the marketplace. After school, Stevenson would be found supporting students at basketball games, football games, and at various functions. He received his teaching degree from Lincoln University, and his master’s degree in teaching from Kansas State University where he graduated with honors and exceptional grades. Stevenson taught, and coached basketball at Northeast Junior High. In also taught math at J.C. Harmon High School, and he later retired from Northwest Middle School (known today as Carl Bruce Middle School). After 32 years of teaching, mentoring, and serving, Stevenson retired from the Kansas City, Kansas public schools district.

Previous slide

Next slide

Old Quindaro Museum

3432 N 29 St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS3432 N 29 St. Kansas City, KS

The Old Quindaro Museum contains the history of Quindaro. The home was constructed by students of Western University. Mr. Anthony Hope is the current president of the Old Quindaro Museum. The goal of the museum is to honor slaves, and families who escaped slavery, and settled in Quindaro. The Museum gives a pictorial history of early African American families who lived in Quindaro. The museum is located inside of a home that was built in 1915. Hope shared that the home may have been the first home in Quindaro that had hot and cold water, along with electricity. In the future, Mr. Hope has a vision to secure funds in order to modernize, remodel, or build a 21st century museum. Some of the businesses that “Old Quindaro Museum” has collaborated with include, Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum, Wyandotte County Historical Society, Kansas City, Kansas City, Kansas Community College, and the Freedom Frontiers Heritage Organization.

Previous slide

Next slide

Quindaro Park

3345 Sewell Ave. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS3345 Sewell Ave. Kansas City, KS

Historians, and community residents have documented that slave snatchers waited at this site in hopes of capturing escaped slaves or freeman. The goal was to take blacks back into slave territories and place them on slave plantations.

Even after the Civil War in the United States ended in 1865, Kansas remained a free state, however bitterness between pro-slavery forces and free-soil advocates in Missouri and the Kansas Territory sustained years after the Emancipation Proclamation was signed. Eventually, the term Jim Crow was applied to the body of racial segregation laws and practices throughout the nation.

As early as 1837, the term Jim Crow was used to describe racial segregation in Vermont. Most of these laws, however, emerged in the southern and border states of the United States between the years 1876 and 1965. They mandated the separation of the races and separate and unequal status for African Americans. The most important Jim Crow laws required that public schools, public accommodations, public transportation, including buses, trains, pools, communities, and parks have separate facilities for whites and blacks (18).

Before the Civil War, and after the Civil War, black code laws were enforced to justify slavery. In Kansas, in 1854, the Kansas Territory was officially established, but the state remained divided on the issue of slavery. During this same year, the territorial legislature met at the school where Andrew Reeder, newly appointed territorial governor, had his offices. During this legislative session the so-called “Bogus laws” were passed in an attempt to perpetuate slavery in Kansas (19).

“Bogus laws” were passed prior to the Civil War, and after the Civil War, in a planned legislative effort under Kansas first legislative elected body of leaders. The goal was to keep slaves in bondage through forced slavery on plantations, and to appease those from southern states who desired to move into Kansas territory and transport their slaves. The Kansas Slavery statutes were widely circulated nationally and often reprinted. Clergyman John McNamara, in his book on his time in Kansas, included the statutes, calling them "the black and cruel Law in the Draco-Kansas Code" (39). Pro-slavery leader Benjamin Stringfellow, on the other hand, boasted to interested southerners that Kansans, "now had laws more efficient to protect slave property than any State in the Union" (40). The importance of enacting strong slavery statutes was central to the pro- slavery cause. If southern settlers were to come to Kansas, it must be safe for them to bring their slaves. Moreover, there was a substantial concern that the number of slaves escaping from western Missouri could rise, as it in fact did. By 1857, the number of runaways had increased tenfold, and the state of Missouri was providing special patrols (41).

Lawrence, Kansas leaders continued to take a strong stand against slavery, and publicly spoke out about the need to completely abolish slavery in Kansas, and throughout the United States. At the same time, the Lawrence, Kansas leadership continued to support the free Quindaro township, despite the "Bogus laws" that were enacted. In fact, John Speer, editor of the "Lawrence, Kansas Tribune", published a broadside on the effective date of the Slavery act, challenging the "gag law" provision, and "Bougus laws", making it a crime to speak or write that "persons have not the right to hold slaves in this Territory. Again, leaders throughout Lawrence, Kansas, wanted to make it clear that they would continue to support the antislavery movement, and that they would not allow slavery to sustain. Despite the "Bogus laws", Lawrence, Kansas, and the Quindaro township not only established a thriving community, but both towns established free parks for blacks. Since slavery was still legal in Missouri, slave catchers would come to Quindaro, with the goal to capture slaves who had escaped slavery. At Quindaro park, many have noted that slave catchers would stand on a hill at what is known as Quindaro Park, in order to find slaves or free blacks to capture and place them on plantations.

Local social historian Luther Smith mentioned that Quindaro Park may have been one of the first parks in the state of Kansas for blacks. No matter how a slave found himself on the southern bank of the Missouri River at that point, open doors awaited at the Quindaro end of the Parkville-Quindaro escapee route. One of these entries was on land close to the Missouri owned by Elisha Sortor whose family had a long history of support for the Underground Railroad reaching back into New York State. Elisha Sortor accumulated farmland on the southern and western borders of the town of Quindaro, not far from the Parkville crossing. One of the family homes stood in Sortor Hollow just west of historic (and present day) Quindaro Park. Although the structure no longer survives, this residence was a station for the Underground Railroad. Elisha Sortor’s great-granddaughter-in-law, Beulah Sortor, recalled the country house in Sortor Hollow: “the house was built into the side of a hill, and there was an apple orchard there (with) living quarters down below. And Norman, (Elisha’s grandson and Beulah’s husband) told me that there were two rooms in the back, and he said this was supposed to have been a safe house for the Underground Railroad. When they took the slaves in, they kept quiet about it, it was protection for the slaves, and protection for themselves (20), (21).

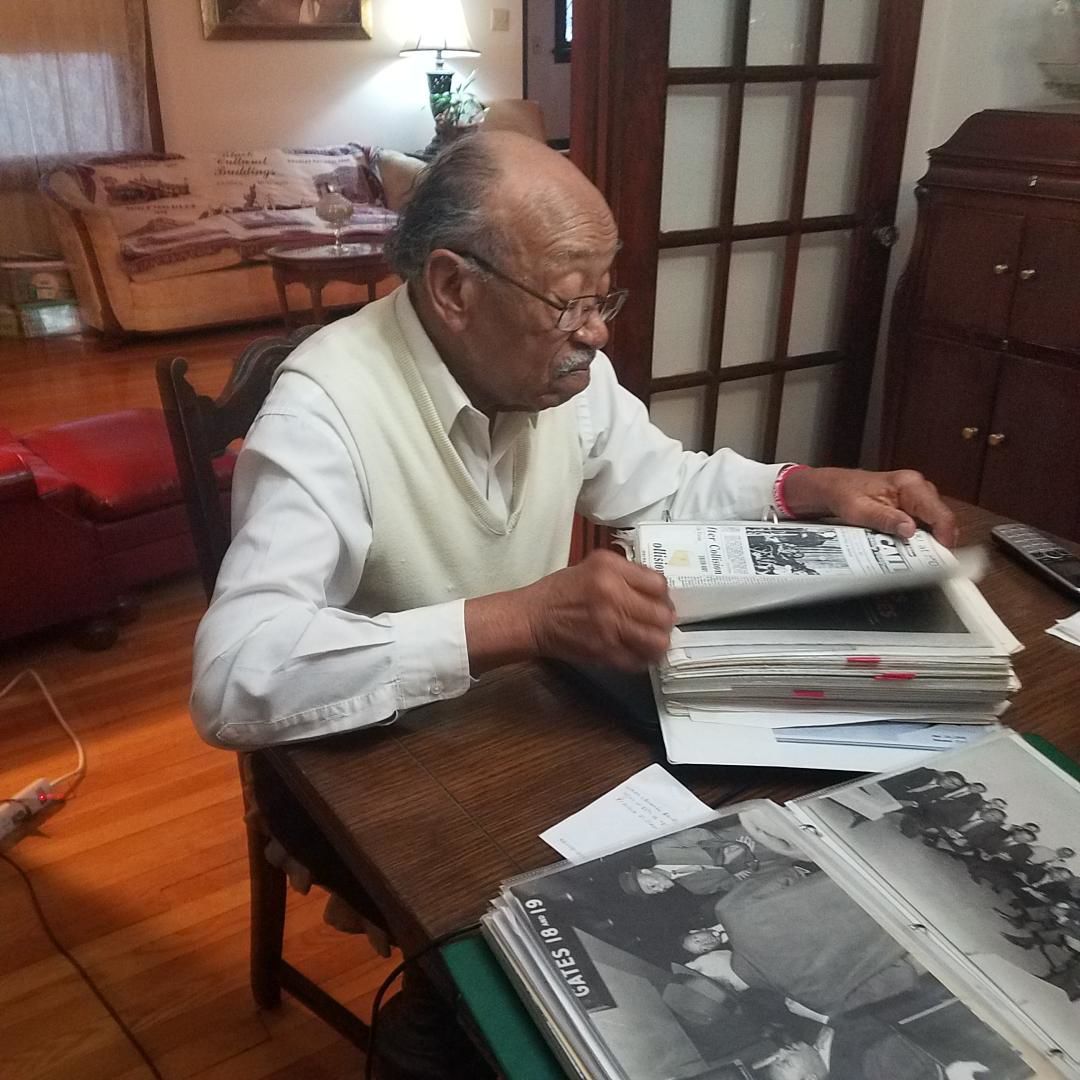

Respected Quindaro historian, Orrin Murray cites, “The Sortor family residence was the biggest Underground Railroad depot there was because whenever anyone in need came by, the family would give them something to eat and a place to sleep” (22), (23). As a child, and as an adult, Luther Smith who was born in Quindaro, KS, and who serves as the curator of the Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum, recalls hearing stories of the Underground Railroad from family members, and from people who grew up in Quindaro. Smith remembers hearing stories about how slave catchers would come to "Quindaro Park" to capture free blacks or escaped slaves who lived in Quindaro (24).

Previous slide

Next slide

Quindaro Township

3507 N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS3507 N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

Early travel through Kansas Territory was facilitated by the identification of particular towns and sites referred to as stations on the border of Oklahoma and Missouri, into Nebraska and Iowa. Locations along waterways such as, the Missouri River were known as “Freedom Crossings,” including the crossing at the bend between Parkville, Missouri and Quindaro, Kansas. (25)

It is estimated that approximately 300 slaves moved in the four years 1855 - 1859 through the antislavery town, Lawrence, Kansas that was founded in the year of 1854 by the New England Emigrant Aid Society with an antislavery mission. That number could be higher, due in part, to the secrecy of the Underground Railroad. Lawrence, Kansas was named after Boston philanthropist and antislavery reformer Amos Lawrence (Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict,1855-1865, KSHistory.org). This particular data equates to about 75 slaves per year, even though the nearby Douglas County was known as pro-slavery. Despite Lawrence, KS being attacked by Douglas County, and by pro slavery forces from Missouri, Lawrence, Kansas managed to sustain the antislavery cause. It seems most passages are attributed to the station referred to as Fort Bain. Fort Bain, was a fortified log house capable of housing 50 people, served as a base of operations for radical abolitionists John Brown, James Montgomery, and its namesake, Captain Oliver P. Bain. With its location close to the Missouri border, Brown and Montgomery could stage raids into that state to liberate slaves and usher them to freedom on the Underground Railroad. The building served as a defensive position against proslavery forces during the "Bleeding Kansas" troubles, and Brown once claimed to have used it to defend against a force of 500 attackers. (26)

Many slaves escaped through the Quindaro township. Data reveals that many slaves settled throughout Wyandotte County, the Quindaro township, Lawrence, KS, Leavenworth, Kansas, and in many towns throughout Kansas, and surrounding states that were known as antislavery communities.

The proximity in time of the founding, development, and active period of the existence of the town of Quindaro is very interesting given the connection between the history of the removal and scattering of the Wyandot people; and the multicultural gathering and collaboration at this site (27). The Wyandot population that relocated from Ohio to Kansas in 1843 was substantially less than 10,000; and estimated to be approximately 700. By 1750, the total European white population had grown to roughly one million in the thirteen colonies and subsequently exploded to 12.5 million Euro-American and 1.75 million African Slaves. In very different ways, both the Wyandot and African slaves found a parcel of land on the Kansas side of the Missouri River to be of nearly sacred significance (27)

Since many cultures and nationalities settled throughout the Kansas and Missouri ‘diaspora’ (meaning a scattering), building a sustainable community, and economy at the present day “Quindaro Township Ruins Commemorative Site” wasn’t an easy endeavor. It took many cultures and nationalities to build a healthy, thriving community. Throughout history an array of cultures have been scattered through involuntary dispersions, and through voluntary dispersions, such as the expulsion of Jews from Egypt, the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the Chinese of Hindus from South Asia during the “coolie’ trade, the Irish immigration resulting from the potato famine, and on through the present day forced scattering of people from original homelands in the Middle East (28)

“Boosterism” began to effect and form the development of the American western frontier in the late 1830s and became rampant as a form of speculative investment between 1830 and 1850. In this economic environment, the town of Quindaro was envisioned, platted, and developed. The date of December 1856 is given as the platting, with groundbreaking in January 1857. By May 1857, a description in the new local newspaper of the construction from the article by Alan Farley “Annals of Quindaro: A Kansas Ghost Town”, copyright 1956, reads, “trees had been removed from several acres of the town site that grading of the hill to the wharf… had progressed so that heavy loads might be hauled… leading into the territory without difficulty. Thirty to forty houses had been built and occupied. A schoolhouse had been opened on May 3, and 16 business houses were in the process of erection. The Quindaro House, the second largest hotel in the territory was opened; the town was well supplied with two hotels, two commission houses, a sawmill of 5,000 feet per day capacity, a stone yard, a carpenter shop, land agencies, surveyor builders, cabinetmakers, and blacksmiths. By August, the first brick house was under construction on P street, the bricks having been burned on the town site. (29)

In January 1859, Quindaro had a population of 800 (and may have reached 1,200 before decline set in), with nearly 100 private houses built. Two hotels sustained in Quindaro, a Harare store, three dry goods stores, four groceries, one clothing store, two drug stores, two meat markets, two blacksmiths, one wagon shop, six boot and shoe shops, and one livery stable. There were also four doctors, three lawyers, two surveyors, and several carpenters and builders. For almost two years, the town boomed, attracting national attention. (30)

In 1860, the severe drought and famine in Kansas that began in 1859 and lasted almost two years, was reported by Eastern Newspapers. Between the mid and late nineteenth century, three severe droughts struck North America, and each had its own effect on the social, ecological, and environmental state of the plains and the west. The drought of the mid 1859’s to the ice 1869’s, or Civil War Drought, added to the near extinction of the American Bison. (31).

From a different perspective, and lens, some critics had different views on why the Quindaro Township became a “Ghost Town”. Some mentioned, “This is the kind of explosive growth that the speculative capital of the Eastern United States non-resident investors created. That kind of growth can be found in real estate speculation, even today. As with any speculation, there is risk, and with economic fluctuation, some investments collapse. In 1862, only five years from the groundbreaking, the Kansas legislature repealed the act that incorporated Quindaro and put the town company out of business.” (32)

By 1863, the town was referred to as a ghost town. This economic collapse was predominantly the result of the general economy across the country from the Advent of the Civil War. (33) The town of Quindaro was one of a number of Kansas territorial river ports founded in the mid-1850s following passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which established Kansas and Nebraska Territories and opened these territories for settlement. The site of Quindaro is located in the west One-half of Section 29, Township 10 South, Range 25 East of the Sixth Principal Meridian, and the East One-half of Section 30, Township 10 South, Range 25 East of the Sixth Principal Meridian, in Kansas City, Wyandotte County, Kansas.

Today, the Quindaro Ruins National Commemorative Site is located on the bluffs of the right bank of the Missouri River, on the present-day northern edge of Kansas City, Kansas, just west of the point at which the river is crossed by Interstate 635 Highway. The location is approximately five miles upstream from the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers and two miles south of Parksville, Missouri. The principal boundaries of the site are North 31st Street on the west, Sewell Avenue on the south, Interstate 635 Highway on the east, and the Missouri Pacific Railroad right-of-way on the north. (34) The commercial district of the Quindaro township was located along Kansas Avenue, the principal North-South Street extending south from the wharf up the bluff slope. This corresponds to the juncture of Sections 29 and 30, as well as the present North 27th Street in Kansas City, Kansas. Two principal commercial streets, Levee and Main, bisected Kansas Avenue along a west-northwesterly to east-southeasterly axis, running parallel to the right bank of the Missouri River as it was then located. Streets numbered first to Tent extend east-west, perpendicular to Kansas Avenue and south of Main Street on the original plat. Lettered north-south streets (A-Y) extended from Tent Street north to Main, with Kansas Avenue in place of Q Street. It should be noted that when the plot of Quindaro was laid out on the ground, an apparent error of one rod in the east-west direction was made. Consequently, all known remains within the town-site are located approximately 16.5 feet to the east of whereby legal description they might by expected to be found. (35)

Local Social historian, Mr. Luther Smith, who was born in Quindaro, mentioned there used to be a streetcar that drove all the way from 27th & Farrow to Minnesota Ave, to the James Street bridge, into Kansas City, Missouri, to Main St., and to Swope Parkway. Smith used to ride the streetcar throughout the city. In addition to riding the streetcar, Smith noted there used to be a big water tank on 29th and Sewell.

It is documented that the world-renowned historian, Dr. John Hope Franklin visited the Quindaro Ruins site. Quindaro town-site was named for Nancy Quindaro Brown, a Wyandot woman who married former Ohio land agent, Abelard Guthrie. The purchase of a portion of this parcel of land from Wyandot tribesmen was expedited by the fact that Guthrie’s wife was a Wyandot. Her name, “Quindaro,” became the name of the township. Quindaro can be translated as “a bundle of sticks.” (36)

However, John M. Walden, Free State editor of the Quindaro Chindowan newspaper, simplified its meaning to, “in union there is strength” (37).

In summary, the plan for a new town was mentioned by developers in the town of Lawrence, Kansas to provide a free-state abolitionist landing on the Kansas side of the Missouri River. The land was obtained by establishing a partnership between Abolitionist Wyandot and The New England Emigrant Aid Company; and to mention again, the town quickly flourished as a natural port for Free Soil advocates. (38). Since the world economy was interconnected, the worldwide economic financial crisis that began in late 1857, would affect the development of the worldwide economy, and it would eventually affect the United States economy. The United States Financial Panic of 1857 was caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy.

Historians, community leaders, social historians, archeologists, and diverse leaders have documented why the Quindaro township declined. In truth, I would argue, that some of the major causes to the decline of Quindaro township were mainly due in part, to legalized slavery that was still in effect throughout the United States of America, legalized racism, several global economic recessions, and the opium addiction crisis before the American Civil War, during the American Civil War, and the opium addiction crisis that effected the mental health of soldiers and diverse citizens in both urban and rural communities. Equally important, systematic economic disenfranchisement hindered the economic growth of the Quindaro township. At the same time, many White Americans did not recognize blacks, Native Americans, and indigenous cultures as citizens of America.

With that being said, if a particular culture is denied the right to vote based on the color of their skin, then the dominant group with economic leverage, is able to control the economic resources, make important political decisions, and create laws that effects the less fortunate in terms of having access to quality education, jobs, health care, healthy foods, and sustainable communities where all people can live in freedom. As I mentioned previously, I believe that various factors contributed to the demise of the Quindaro Township. Despite the various factors that hindered the economic growth of the Quindaro Township, the community managed to survive. Equally important, caring community leaders, and concerned citizens managed to preserve several historic sites, and Underground Railroad freedom passageways throughout the community. Today, diverse leaders throughout Kansas, the United States of America, and throughout the world continue to envision innovative ways to sustain the Quindaro Township for future generations.

Previous slide

Next slide

Statue at Wyandotte County Historical Society and Museum

631 N 126th St. Bonner Springs, KS

DIRECTIONS631 N 126th St. Bonner Springs, KS

The monument is dedicated to the ethnic communities in Wy Co, including African Americans. The goal of the “Wyandotte county historical museum” is to identify, collect, preserve, interpret, and disseminate material and information pertaining to Wyandotte County history in order to assist the public in understanding, appreciating, and assisting in the preservation of the heritage of this county.

Previous slide

Next slide

Sumner High School

837 New Jersey Ave. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS837 New Jersey Ave. Kansas City, KS

In 1905, Sumner High School opened as a result of an incident that occurred in April 1904. Because of the hostility at the school the following day, school was canceled for the balance of that school year. When the school opened in September of 1904, a split schedule was implemented: During the day the school operated as the Kansas City, Kansas High School. This name was selected by the Board of Education but was highly protested by the Balck community. A meeting was held and the name was changed to Sumner High School, in honor of abolitionist, and U.S. Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts.

At the January 1905 state legislative session, House Bill No. 890, also known as the “Segregations Bill,” was passed. This bill was specifically designed to govern the high schools of Kansa City, Kansas, and to amend section 6290 of the General Statutes of 1901. It reversed the provision for mixed high schools in the State of Kansas.

Sumner High School became the only all African American High School in the State of Kansas. J.E. Patterson was appointed as its first principal. The first location was 9th street and Washington Blvd. In 1940, the school moved into a new building at 8th Street and Oakland Avenue. The Sumner Division of Kansas City, Kansas Junior College was housed in Sumner High School from 1923 until 1951 because African Americans were not allowed to attend school at the main campus. John A. Hodge was appointed Assistant Dean of the Junior College until the two divisions integrated in 1951. The faculty at Sumner High School was carefully selected and were of the highest caliber. The faculty Roster of 1926 - 1927 indicated that forty-one percent held master’s degrees, and by 1935, sixty-one percent of the faculty held master’s degrees (42).

Sumner High School became known for its academic achievements, and for graduating several Phi Beta Kappas. The distinctive honors hailed from: The University of Kansas (7) University of Chicago, Vassar University, and Wellesley College. Because of the academic achievements of many of its graduates, Sumner High School became known as “A Citadel of Learning” and the Harvard of the Midwest." (43).

Notable Educators

Leon Brady, educator and Band Director

Leon Brady led a group of students from Sumner High School to Paris, France. In May 1972, The Sumner High School Jazz Band was invited to participate in the International Jazz Festival in Paris, France from July 4th - 5th, in the year of 1972. Twenty five thousand dollars was necessary to cover the expenses for this event. The Northeast community raised approximately eighty percent of this amount. U.S. Senator Robert Dole was very helpful in this venture. The Sumner High School Jazz Band was one of only seven bands invited from the United States and the only one from the Midwest.

Leon Brady led a group of students from Sumner High School to Paris, France. In May 1972, The Sumner High School Jazz Band was invited to participate in the International Jazz Festival in Paris, France from July 4th - 5th, in the year of 1972. Twenty five thousand dollars was necessary to cover the expenses for this event. The Northeast community raised approximately eighty percent of this amount. U.S. Senator Robert Dole was very helpful in this venture. The Sumner High School Jazz Band was one of only seven bands invited from the United States and the only one from the Midwest.

Leon Brady was a world-class Band Director at Northeast Junior High School & Sumner High School. Many of his students would later go on to accomplish amazing things around the world. Mr. Brady was known for being a caring, but firm educator who believed in all of the students under his care. Brady took the first jazz band from the state of Kansas to Perform in Paris, France. The band from Sumner High School included a list of amazing musicians such as Freddie Allen, Felicia Smith, Jeffery Lewis, Michael Gregory, Orlando Bryant, John Washington Mark Stafford, Cragye Lindesay (Recording engineer/Multi-instrumentalist/producer), John Weatherspoon, David Bailey, Ronald Henderson, Steven Duncan, Charles Williams, Eva Cage, Reginald Watkins, (Elderstatemen of Jazz Organist & Pianist) Roger Bettis, Richard Wilson, Don Davis, Harold Dwight and Russell Hornsby. The band took first place at the jazz festival, and recorded a record while in Paris, France.

The following persons served as principal of Sumner High School: J.E. Patterson 1904 - 1908; John M. Marquess 1908 - 1916; John A Hodge 1916-1951; S.H. Thompson, Jr., 1951 - 1972; Jerry Collier, 1972 - 1973; James Boddie, 1973 - 1978. Recent principals are not listed but can be located in the Sumner Library. Sumner High School was closed in 1978 by a Federal Court Order. The name was changed to Sumner Academy of Arts and Science. The mascot was changed from the Spartan to the Sabres (African American History (Northeast Area), Wyandotte County Historical Society).

Noted Alumni

Fernando Gaitan - 1966 graduate. Became the Chief Judge for the Western District of Missouri.

Gaitan was listed by Lawdragon, a national legal magazine, as one of the 500 leading judges in America.

John McLendon ; 1932 graduate. McLendon was a member of the basketball team, the only team. His coach was Beltrome Orme, and the team had a 17-0 record that year. He was the first African American to receive a Bachelor of Science degree in physical education from the University of Kansas. While at KU, he was the advisee to Dr. James Naismith, the inventor of basketball. He received a Master of Arts in Physical Education from the University of Iowa in 1937. He coached at North Carolina College for Negroes, 1937-1952, Hampton Institute, 1952-1954, Tennessee A&I, State University 1954 - 1959, Kentucky State University, 1959 - 1963, and Cleveland State University, 1966 - 1969. As head coach at colleges and universities, his lifetime record is .760 percent (523 victories and 162 losses). His far-reaching list of firsts include being the first coach to win three consecutive national titles, (Tennessee A&I University (1957 - 1959), the first black coach of an integrated professional team, the American Basketball League (ABL) Cleveland Pipers, the first black head coach at a predominantly White College (Cleveland State), the first Black Coach in the American Basketball Association (ABA) Denver Rockets, the first black on the Olympic Staff. These are only a few of his accomplishments.

John McLendon ; 1932 graduate. McLendon was a member of the basketball team, the only team. His coach was Beltrome Orme, and the team had a 17-0 record that year. He was the first African American to receive a Bachelor of Science degree in physical education from the University of Kansas. While at KU, he was the advisee to Dr. James Naismith, the inventor of basketball. He received a Master of Arts in Physical Education from the University of Iowa in 1937. He coached at North Carolina College for Negroes, 1937-1952, Hampton Institute, 1952-1954, Tennessee A&I, State University 1954 - 1959, Kentucky State University, 1959 - 1963, and Cleveland State University, 1966 - 1969. As head coach at colleges and universities, his lifetime record is .760 percent (523 victories and 162 losses). His far-reaching list of firsts include being the first coach to win three consecutive national titles, (Tennessee A&I University (1957 - 1959), the first black coach of an integrated professional team, the American Basketball League (ABL) Cleveland Pipers, the first black head coach at a predominantly White College (Cleveland State), the first Black Coach in the American Basketball Association (ABA) Denver Rockets, the first black on the Olympic Staff. These are only a few of his accomplishments.

Noted Alumni

Delano Lewis – first African American president and executive officer of NPR, etc.

Harold Hunter - 1950 graduate. First African American to sign with an NBA team. He had been inducted into the Helms Hall of Fame, the Naismith Hall of Fame, the College Hall of Fame, the Kansas Hall of Fame, and others. Julius Erving (Dr. J) NBA Hall of Famer calls him, “The Father of Black Basketball.” John McLendon, who graduated from Sumner High School, coached him.

Harold Hunter - 1950 graduate. First African American to sign with an NBA team. He had been inducted into the Helms Hall of Fame, the Naismith Hall of Fame, the College Hall of Fame, the Kansas Hall of Fame, and others. Julius Erving (Dr. J) NBA Hall of Famer calls him, “The Father of Black Basketball.” John McLendon, who graduated from Sumner High School, coached him.

Noted Alumni

William Patrick Foster - 1937 graduate. American’s Bandmaster, The Man Behind the Baton, and The Law were a few names given to him. Graduated from the University of Kansas 1941. The University of Kansas and the Alumni Association conferred the Citation for Distinguished Service upon William Patrick Foster. He was the first recipient of the United States Achievement Academy Hall of Fame Award and the first Outstanding Education Award by the School of Education Society of the University of Kansas Alumni Association. In 1994, he was elected President of the American Band Masters Association. (44).

Garland Smith - artist Garland Smith was born on November 26, 1935, in Kansas City, Kansas. He got his artistic start drawing pencil sketches at the Plaza Art Fairs while still in high school. He attended Sumner High School and graduated in 1954. Mr. Smith was a true activist serving on the Bonner Springs School Board for ten years as well as the Kansas Legal Aid Board. He had an entrepreneur's spirit, he opened his own business titled, “Garland Smith Interior Decoration Company.” (45)

Garland Smith - artist Garland Smith was born on November 26, 1935, in Kansas City, Kansas. He got his artistic start drawing pencil sketches at the Plaza Art Fairs while still in high school. He attended Sumner High School and graduated in 1954. Mr. Smith was a true activist serving on the Bonner Springs School Board for ten years as well as the Kansas Legal Aid Board. He had an entrepreneur's spirit, he opened his own business titled, “Garland Smith Interior Decoration Company.” (45)

Noted Alumni

Marjorie Cate, M.D - medical doctor

Cate is a 1948 graduate of Sumner High School, and the first Black woman to earn a medical degree from the University of Kansas. She was honored by the University with an Academic Society dedicated in her name. (University Honors the first Black Woman to earn a medical degree from Kansas University, Greg Peters). For additional information on Dr. Cate, see this YouTube video clip.

Previous slide

Next slide

Vernon Elementary School

3436 N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS3436 N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

Today, Vernon Elementary School is known as the Vernon Multi-Purpose Center. The Vernon Elementary School was located on the present site of the Vernon Center, and was operated by Rev. Eben Blachly, Presbyterian Minister who struggled to find funds and services.

In the year of 1865, during the closing of the Civil War, when the population of the Quindaro Township reached 429 African Americans, a group of Quindaro citizens decided to establish a formal school. A group of men chartered Quindaro Freedmen’s University. The University was supported through donations, and with two teachers throughout its history - Even and Jane Blachly. The school closed in 1877 upon the death of Rev. Blachly. In 1879, the school’s trustees took out a mortgage on part of the property of the Freedmen’s University in an attempt to keep it open. (46)

The Vernon School was known as The Colored School of Quindaro. It opened in 1858. The original school’s purpose was built to educate African American children in the abolitionist community of Quindaro. The school began operation in the years leading up to the Civil War when it provided instruction to African Americans, including many former slaves who had just arrived in the territory of Kansas. The segregated school ran by its own district (#17) with a board of all African Americans. By the 1930s, the school fell to despair and became overcrowded. In 1936, a brick school took the place of the old building. The new school had 4 rooms and served the 1st through 8th grade. In 1950, two rooms were added. This facility was built using President Roosevelt’s New Deal Program. The Colored School of Quindaro became Vernon School after William Tecumseh Vernon. At the time Vernon was only 25 years old. As an accomplished speaker and writer, Vernon became an African American Leader from Kansas City and served as the president at the Western University, who is credited with expanding the university’s curriculum and state funding.

In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Vernon as Register of the US Treasury, the highest post ever achieved by an African American, at the time. Vernon later became consecrated as a bishop with the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and worked as a missionary in South Africa (47).

In 1954, the Brown Vs. Board of Education of Topeka landmark case desegregated schools across the country. The next year, about one third of the Vernon School’s children were sent to integrate the Quindaro Elementary School. Due to desegregation, and partially due to a decreasing population of Quindaro, the Vernon School closed in 1971. The building turned into a community center, which is still in use. In 2004, the National Historic Register added the building to its list.

Today, the Vernon School is called the Vernon Multi-Purpose Center. Its mission is to function as an outreach facility, serving Wyandotte County citizens. The Center’s purpose and goal is to enhance the general, physical, and wellbeing of the community it serves. The center also houses the Underground Railroad Museum. It supports and assists the historical preservations of the documents, secured by the museum. (48) The Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum currently resides inside of the Vernon Multi-purpose Center. The museum houses an array of primary, and secondary source historical documents, photos, and artifacts that cover the history of Quindaro, and the Underground Railroad.

Smith, who is a local social historian, and a dedicated leader who was born in Quindaro is committed to preserving the stories of Quindaro. He is the main visionary, and creator of the Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum. Smith mentioned his mother was born in Quindaro in 1917, and she graduated from Vernon Elementary School. She also graduated from the former historically black college, Western University, that is located across the street from the Vernon Center. Smith mentioned that the school was named after Bishop William Tecumseh Vernon, who was a former president of Western University, a Bishop, a servant, and a former United States Treasurer (49). Smith mentioned that in 1872, the black school and a white only school (27th and Farrow), were built only a few blocks apart. Records show that only 2,000 dollars were allocated to help build the black school, but Smith notes that the white school received a significantly larger amount.

He believes the school received 5,000 dollars. Note that during this time, blacks and slaves were not allowed to vote, hold any political power, attend school with whites, and they were not even considered citizens of the United States of America. Just five years prior to the opening of the of “The Colored Normal School” in 1862, in 1857, judges decided in Missouri’s Dred Scott Case the United States Supreme Court upheld slavery in United States territories, and denied the legality of black citizenship in America, and declared the Missouri Compromise to be unconstitutional. (50)

Clarina Nichols, author and lecturer regarding issues surrounding abolition, women’s rights, suffrage, temperance, etc., left a rich description of stations and secants throughout Quindaro. Nichols, co-editor of the “Quindaro Chindowan” (Newspaper), and one of the conductors on the Quindaro Underground Railroad. (51)

In 1882, the editor of the Wyandotte Commercial Gazette invited Nichols to write her reminiscences of Quindaro. Her letters to the editor contain one of the few surviving eye-witness accounts of Quindaro Underground Railroad operations (52). Some of the businesses that the “Old Quindaro Museum” has collaborated with include, Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum, Wyandotte County Historical Society, Kansas Community College, the Freedom Frontiers Heritage Organization, Kansas City Kansas Public Library, University of Kansas, University of Kansas State, University of Missouri at Kansas City, diverse school districts, and AmeriCorps.

Previous slide

Next slide

Western University

NE Corner of Quindaro Blvd. & N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONSNE Corner of Quindaro Blvd. & N 27th St. Kansas City, KS

Western University was the first historically Black University west of the Mississippi River, and the first African American University in Kansas. The university operated from 1881-1943. (53)

The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church gave a second life to the old Freedman’s University, when it was reopened in 1881 with the name “Western University”. At the same time, the AME church jointly operated Wilberforce University in Ohio for African American Students, along with 13 others. African Americans constituted the entire Board of Western University, and funding resulted in Kansas students receiving discounts in fees and tuition. (54)

The school originated by the work of Presbyterian Minister Eben Blachly, who played a key role in educating free blacks in Territorial Kansas Town of Quindaro in 1857. After the Civil War, Blachly expanded the school, and in the year of 1869 the State of Kansas donated land as the student population grew. (55)

The school’s curriculum followed Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee institutes’ model of Vocational Training. In 1896, the A.M. E Church assigned Bishop William Tecumseh Vernon to serve as president of the University. As an accomplished speaker and writer, Vernon developed into a significant African American leader throughout Kansas, the United States, and South Africa. Vernon was one of the key leaders who contributed to expanding the university’s academic curriculum. In addition to that, Vernon helped secure state funding, so that the school could remain open. (56).

Western University followed the industrial education model developed by Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes, but it also educated future Kansas teachers through its Normal School and provided officer training through its military department. Students were also able to earn a B.A. in Liberal Arts. The institution’s celebrated Music Department produced, The Jackson Jubilee Singers, who toured nationally and were widely acclaimed rivals to The Fisk Jubilee Singers. Western University closed in 1943 when its programs were absorbed into the Kansas State Industrial School. For much of its 62-year history, Western University helped to prepare African American students to fully participate in American society. (57)

Famous Alumni

Etta Moten Barnett

Etta Moten, a multifaceted pioneer in the world of entertainment, was born in Weimar, Texas in 1901. She was raised as the only child of her parents, Freeman Moten, a Methodist minister, and his wife Ida Mae Norman. In 1915, Rev. Moten moved to Kansas City where Etta Moten began singing in Church choirs. She attended Western University in Quindaro, and later she studied voice and drama at the University of Kansas in the year of 1924 (Blackpast.org). She earned a BA in voice and drama in 1931. An actress and contralto vocalist. She was best known for her signature role of “Bess” in Porgy and Bess. She moved to New York City, where she performed as a soloist with the Eva Jessy Choir. On January 31, 1933, she became the first African American star to perform at the White House. In the 1942 revival of Porgy and Bess, she accepted the role of “Bess,” but she would not sing the n-word, which Ira Gershwin later wrote out of the libretto (58). She and her husband Claude Barnette, founder of the Negro Associated Press, traveled during the late 1950s as members of the U.S. delegation to Ghana. She also represented the United States at the Independence ceremonies of Nigeria, Zambia, and Lusaka (58).

Etta Moten, a multifaceted pioneer in the world of entertainment, was born in Weimar, Texas in 1901. She was raised as the only child of her parents, Freeman Moten, a Methodist minister, and his wife Ida Mae Norman. In 1915, Rev. Moten moved to Kansas City where Etta Moten began singing in Church choirs. She attended Western University in Quindaro, and later she studied voice and drama at the University of Kansas in the year of 1924 (Blackpast.org). She earned a BA in voice and drama in 1931. An actress and contralto vocalist. She was best known for her signature role of “Bess” in Porgy and Bess. She moved to New York City, where she performed as a soloist with the Eva Jessy Choir. On January 31, 1933, she became the first African American star to perform at the White House. In the 1942 revival of Porgy and Bess, she accepted the role of “Bess,” but she would not sing the n-word, which Ira Gershwin later wrote out of the libretto (58). She and her husband Claude Barnette, founder of the Negro Associated Press, traveled during the late 1950s as members of the U.S. delegation to Ghana. She also represented the United States at the Independence ceremonies of Nigeria, Zambia, and Lusaka (58).

Eva Jessye

Eva Jessye was a pioneer in the world of African American music and is recognized as the first black woman to receive international distinction as a choral director. She was born in Coffeyville, Kansas on January 20, 1895 to Albert and Julia Jessye. Jessye was influenced by the singing of her great-grandmother and great-aunt. Jessy developed an early love of traditional spirituals. At the age of thirteen, she attended Western University in Kansas City, Kansas where she studied poetry and oratory. In addition to singing in Western’s concert choir, she gained experience coaching several male and female student choral groups. As her professional career grew, she moved to New York in 1926 and directed spirituals, jazz, and a light opera choir called the Dixie Jubilee Singers. Under her direction, the group, later named the Eva Jessy Choir, enjoyed a successful career which lasted more than thirty years and included a regular spot on the radio program, “Major Bowes Family Radio Hour”.

Eva Jessye was a pioneer in the world of African American music and is recognized as the first black woman to receive international distinction as a choral director. She was born in Coffeyville, Kansas on January 20, 1895 to Albert and Julia Jessye. Jessye was influenced by the singing of her great-grandmother and great-aunt. Jessy developed an early love of traditional spirituals. At the age of thirteen, she attended Western University in Kansas City, Kansas where she studied poetry and oratory. In addition to singing in Western’s concert choir, she gained experience coaching several male and female student choral groups. As her professional career grew, she moved to New York in 1926 and directed spirituals, jazz, and a light opera choir called the Dixie Jubilee Singers. Under her direction, the group, later named the Eva Jessy Choir, enjoyed a successful career which lasted more than thirty years and included a regular spot on the radio program, “Major Bowes Family Radio Hour”.

In 1935, the Eva Jessy Choir auditioned for and was cast as the official choir for the first production of George Gershwin’s folk opera Porgy and Bess. Jessye and her choir toured with the show, earning international acclaim. They were even named the official choral group for the March on Washington in 1963 (blackpast.org). In addition to honorary doctorates from several universities, they awarded Jessy a Doctor of Determination Certificate from the University of Michigan’s Department of African American Studies in 1976. Kansas governor Robert Bennett declared October 1, 1978 “Eva Jessy Day” and in 1982 she was named the “Kansas Ambassador for the Arts” by Governor John Carlin (59). (60)

Charles Henry Langston, notable educator and Civil Rights leader in Kansas

Charles Henry Langston, a famous educator who attended Oberlin’s college preparatory school before moving to Leavenworth, Kansas. The grandfather of possibly America’s most famous African American poet, playwright, novelist, travel writer, “Dean of Negro Writers in America”, and the Negro Poet Laureate”. (61)

Charles Henry Langston, a famous educator who attended Oberlin’s college preparatory school before moving to Leavenworth, Kansas. The grandfather of possibly America’s most famous African American poet, playwright, novelist, travel writer, “Dean of Negro Writers in America”, and the Negro Poet Laureate”. (61)

Charles H. Langston, born on a plantation in Louisa County, Virginia, in 1817, was an exceptional African American educator and civil rights leader. Langston lived an exemplary life that seemingly confronted and tried to correct racial injustice at every turn. He was part a Native American, and part African American. In September 1834, the three Langston brothers were taken from the Virginia plantation to new lands beyond the Allegheny Mountains in the free state of Ohio. Shortly after moving to Ohio, Langston was enrolled in Oberlin’s college preparatory school. Registering in the fall semester of 1835, they were the first African Americans enrolled in Oberlin. At a state convention in Buffalo, New York, in September 1852, Langston proposed black emigration and colonization in masse from the United States to Central or South America where the emigrants might “unite with some Government there, and then make the demand upon the United States to liberate their brethren from their bonds.” (62)

In April 1862, one year after the Civil War began, Charles Langston left Ohio for Leavenworth, Kansas to work among the contrabands. During the Civil War, enslaved African Americans who ran away were welcomed into Union military camps in the Southern states and declared contraband of war. This declaration freed slaves, deprived the slaveowners of their human property, and weakened the ability of the South to carry on the war. In Kansas, contrabands concentrated in towns and adjacent rural districts in the eastern part of the state near the Missouri border. The African American population of Kansas increased from 627 in 1860 to 12,527 in 1865, 8.9 percent of the state’s total population. In the year of 1865, 30 percent of the 12,527 contrabands, or 4,705, were living in Leavenworth, Lawrence, Atchison, Fort Scott, Mound City, Osawatomie, and Topeka. The greatest concentration of contrabands was in Leavenworth, where 2,455 blacks lived in 1865, nearly one-fifth of the blacks in the state. According to the Leavenworth Daily Conservative of February 7, 1862, “The city is full of contrabands,’ alias runaway negroes from Missouri; of home. It is said there are a thousand in the neighborhood. They are of all ages and character. (63)

In the year of 1867, the Impartial Suffrage Association held a meeting in Lawrence, Kansas, on September 5th, 1867. Many notable pioneer women in the woman’ rights movement who were eloquent and successful lectures came to Kansas from eastern states. Some of these women included Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, and Reverend Olympia Brown. (64)

William Tecumseh Vernon, President of Western University.

An eloquent orator who gained a national reputation for his leadership skills. President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to serve as Register of the US Treasury in 1906; and in 1912 he was reappointed to that position by President William Taft. He retired from government service in 1912 to return to school administration and the ministry. In 1920, he was elected to serve as the Bishop of the A.M.E. Church in South Africa where he fostered the building of churches and schools for four years. When he returned to the United States in 1924, he continued to serve as Bishop in areas throughout the Midwest and the South. He returned to Kansas in 1933 to accept an appointment by Governor Alfred Landon to serve as superintendent of the State Industrial Department of Western University. Five years later he retired and spent his remaining years in Kansas City, Kansas. (65)

An eloquent orator who gained a national reputation for his leadership skills. President Theodore Roosevelt appointed him to serve as Register of the US Treasury in 1906; and in 1912 he was reappointed to that position by President William Taft. He retired from government service in 1912 to return to school administration and the ministry. In 1920, he was elected to serve as the Bishop of the A.M.E. Church in South Africa where he fostered the building of churches and schools for four years. When he returned to the United States in 1924, he continued to serve as Bishop in areas throughout the Midwest and the South. He returned to Kansas in 1933 to accept an appointment by Governor Alfred Landon to serve as superintendent of the State Industrial Department of Western University. Five years later he retired and spent his remaining years in Kansas City, Kansas. (65)

Rev. Abram Grant

Educator and bishop of the AME church.

Educator and bishop of the AME church.

Robert B. Jackson

Jackson joined Western University faculty in 1902. A music major at the University of Kansas, he built a widely acclaimed music program at Western University. Created vocal, orchestra, and band. Organized the Jubilee Singers, whose members include Eva Jesse and Douglas Holt. Western University became Nationally known as one of the best in the nation, and its music department was renowned as the preeminent training center for African-America musicians in the Midwest. In 1920, the Music program required mandatory private lessons and 3 1/2 hours of daily practice. (66)

Jackson joined Western University faculty in 1902. A music major at the University of Kansas, he built a widely acclaimed music program at Western University. Created vocal, orchestra, and band. Organized the Jubilee Singers, whose members include Eva Jesse and Douglas Holt. Western University became Nationally known as one of the best in the nation, and its music department was renowned as the preeminent training center for African-America musicians in the Midwest. In 1920, the Music program required mandatory private lessons and 3 1/2 hours of daily practice. (66)

Previous slide

Next slide

Westlawn Cemetery

4101 State Ave. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS4101 State Ave. Kansas City, KS

Sec 39A, Block/row 37, gr/plot 3

Gravesite of Ada Brown

Blues Singer Ada Brown (1890 – 1950) was born in Kansas City, Kansas, on May 1, 1889. Brown is the daughter of H.W. and Anna (Morris) Scott. She is the cousin of James Scott, the noted ragtime composer and pianist. During her career, Brown was billed as “Queen” of Blues,”. She is often omitted from the annals of jazz greats. She was born into a musically inclined family and sang in church as a child before her career in 1910 at Bob Mott’s Pekin Theater in Chicago. It was noted that she worked in Paris and Berlin, then became a regular with the Bennie Moten Band during the early 1920s. From the mid-1920s, Brown did widespread theater tours throughout the U.S. and Canada and appeared in black revues and musical comedies up and down Broadway. Brown was featured at the London Palladium in the late ’30s and appeared with Fats Waller in the film Stormy Weather (1943). One of her last appearances was in Memphis Bound (1945), shortly before her retirement. In addition to her amazing musical talents, Brown was one of the original incubators of the Negro Actors Guild of America in 1936 (67).

Blues Singer Ada Brown (1890 – 1950) was born in Kansas City, Kansas, on May 1, 1889. Brown is the daughter of H.W. and Anna (Morris) Scott. She is the cousin of James Scott, the noted ragtime composer and pianist. During her career, Brown was billed as “Queen” of Blues,”. She is often omitted from the annals of jazz greats. She was born into a musically inclined family and sang in church as a child before her career in 1910 at Bob Mott’s Pekin Theater in Chicago. It was noted that she worked in Paris and Berlin, then became a regular with the Bennie Moten Band during the early 1920s. From the mid-1920s, Brown did widespread theater tours throughout the U.S. and Canada and appeared in black revues and musical comedies up and down Broadway. Brown was featured at the London Palladium in the late ’30s and appeared with Fats Waller in the film Stormy Weather (1943). One of her last appearances was in Memphis Bound (1945), shortly before her retirement. In addition to her amazing musical talents, Brown was one of the original incubators of the Negro Actors Guild of America in 1936 (67).

Gravesite of James "Little Professor" Scott

James Sylvester Scott (1886 – 1938) is referred to as one of “The two greatest ragtime composers.” Scott fashioned rhythmically ebullient, technically challenging scores that enrich the core literature of classic ragtime. (68) Scott was born in Neosho (Newton County), Missouri, on February 12, 1885. He is the second of six children of James Scott and Molly Thomas Scott, who had migrated to southwestern Missouri from North Carolina after their marriage in 1878. Scott was introduced to music at home in Neosho where his mother passed on her approach to music to her children, teaching all six of them to play the piano by ear. Scott may have studied music at the segregate Lincoln School in Neosho, but, like most blacks of his era, he seems to have taught himself most of what he needed to know. Even finding a piano on which to practice was a problem because the Scotts were too poor to own one.

James Sylvester Scott (1886 – 1938) is referred to as one of “The two greatest ragtime composers.” Scott fashioned rhythmically ebullient, technically challenging scores that enrich the core literature of classic ragtime. (68) Scott was born in Neosho (Newton County), Missouri, on February 12, 1885. He is the second of six children of James Scott and Molly Thomas Scott, who had migrated to southwestern Missouri from North Carolina after their marriage in 1878. Scott was introduced to music at home in Neosho where his mother passed on her approach to music to her children, teaching all six of them to play the piano by ear. Scott may have studied music at the segregate Lincoln School in Neosho, but, like most blacks of his era, he seems to have taught himself most of what he needed to know. Even finding a piano on which to practice was a problem because the Scotts were too poor to own one.

Like the young Scott Joplin, who practiced on pianos in the homes of white people for whom his mother was a maid, the young Scott sought out keyboards in neighbors’ homes, public buildings, and local music stores. Scott performed in Kansas City, and published a song titled, “Kansas City Rag” in 1907. Scott’s career as a ragtime composer got under way in 1903 when Charles R. Dumar’s city alderman, director of the Carthage Light Guard Band from 1885, and owner of Dumars Music at 109 Such Main Street, arranged for Scott to break into the music business. In that year Durmars underwrote the printing of Scott’s Summer Breeze”, originally titled “A Summer Zephyr”, and thus established the young pianist as a published composer whose inclusion reached beyond the saloons. The Carthage Evening Press appeared to have little difficulty understanding the idea of intrinsic musical talent, labeling Scott a “musical prodigy.” (69)

According to his cousin Patsy Thomas, Scott was a small man who weighed about 140 pounds, was diffident and unassuming, preoccupied by his world of music. People called him the Little Professor: He always walked rapidly, looking at the ground, would pass you on the street and never see you, seemed always deep in thought. If anyone spoke to him on the street, he would jump, look surprised and pleased. His parting words would always be, “Will you be home tomorrow? O.K., I’ll come over and play my new piece for you.” Don Scott, James’s great-nephew, confirms the impression of a discreet person and adds a revealing insight: “Yea, I’ve heard several people that knew him. He was a quiet type of man. He loved family, but he was mostly wrapped up in his music. They had a name they called him. They used to call him the Professor, because all he wanted to do was to play music and write music and talk music. (70)

Since the popularity of ragtime faded by the late 1910s, and the zinc mining, which had sustained the prosperity of southwestern Missouri, declined abruptly after World War 1. Most of Scott’s publishing career was already behind him when, by the early 1920s, he moved to Kansas City, Kansas, immediately across the Missouri River from the better-known Kansas City, Missouri. In 1922, when his last rag was published, James Scott was listed in the city directory as living at 402 Nebraska Avenue, Kansas City, Kansas. For the next ten years, during his professional active years in Kansas City, Scott had a solid career as a theater musician, bandleader, and arranger. He worked at three vaudeville and movie theaters: the Panama Theater at 1709 East Twelfth Street near Woodland, the Lincoln Theatre at Eighteenth and Lydia streets, and the Eblon Theater at 1822 Vine Street.

Although Scott’s name does not appear in the weekly advertisements of the Kansas City Call for those years, Kansas City musicians say that he was among the top professionals in the black music business (71). Classical ragtime, nevertheless, was associated with important social developments in the age of Booker T. Washington. It was noted that Washington did not approve of the increasingly popular saloons and wine bars; he feared the adverse influence on the morals of Tuskegee students of these giddy, decadent environments in which ragtime was often played. Washington therefore never endorsed ragtime, even if he did declare it less racially offensive than “coon” songs. With that being said, Scott took an active role in the black community affairs, therefore marrying his music to African American ambitions (72) & (73) other Ragtime composer – Westlawn Cemetery, KCK (Section 60, row 20 to 23, no grave/plot #)

Previous slide

Next slide

Wyandot National Burying Ground

641 Minnesota Ave. Kansas City, KS

DIRECTIONS641 Minnesota Ave. Kansas City, KS

When researching the significance of African American sites throughout Wyandotte County, Kansas, and African American Underground Railroad heroes, l hope that diverse leaders, and cultures will see how indigenous people are interconnected, have advocated for each other throughout history, have overcome bigotry, have survived war, have rose above oppressive systems, and have gained victory over systematic and economic racism.