QUANTRILL'S RAID ON LAWRENCE:

A WALKING TOUR

Swipe right to learn more at each stop.

"[The evening before the attack,] how bright—how glowing with happiness and prosperity seemed the future—how little we dreamed of the horror which even then was hovering over us…"

— Sarah Fitch, survivor

In 1863, nine years of national and regional tensions led to the deadliest day in the history of Lawrence. This town of about 2,500 citizens had become famous as a symbol of the antislavery cause and the new state of Kansas. That August, William Clarke Quantrill—a former Lawrence resident and now a leader of Confederate guerrilla fighters—determined to destroy the town, obtain plunder, and kill its adult male residents. Striking so deep into Kansas would be an impressive achievement and avenge wrongs which Quantrill and his men believed that Union supporters had inflicted on Missourians.

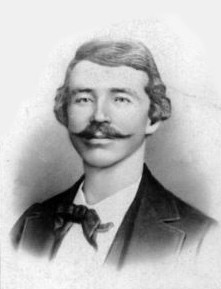

William Clarke Quantrill

Quantrill gathered from 300-400 “bushwhackers” in Missouri on August 18 and rode for Lawrence, eluding Union troops along the way. “The attack was perfectly planned,” one witness recounted. “Every man seemed to know his place. … The order was to burn every house and kill every man."

The citizens of Lawrence had been subjected to several false alarms of attack over the previous two years of the Civil War, and the town now sat totally unprepared. Moreover, many of the male residents who could have resisted an assault were away serving in the Union Army or engaging in business.

The citizens of Lawrence had been subjected to several false alarms of attack over the previous two years of the Civil War, and the town now sat totally unprepared. Moreover, many of the male residents who could have resisted an assault were away serving in the Union Army or engaging in business.

This 1.5-mile walking tour guides users to 10 locations in downtown Lawrence, Kansas.

Scroll down to begin the tour.

MAPScroll down to begin the tour.

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 1

South Park

DIRECTIONSSouth Park

At about 5 AM on August 21, 1863, Quantrill and his raiders reached the outskirts of Lawrence and paused on a summit overlooking the town. After giving orders to his lieutenants, Quantrill ordered the attack. The guerrillas rode northwest through outlying homesteads and South Park toward their objective of the downtown business district.

"When they came to the high ground facing Massachusetts street, not far from where the park now is, the command was given in clear tones, 'Rush on to the town.' Instantly the whole body bounded forward with the yell of demons."

— Rev. Richard Cordley, Lawrence resident

During the raid, some residents hid themselves in bushes and swales throughout the park. On the northwest edge of South Park, at what is now 1123 Vermont Street, stood the home of Rev. Hugh D. Fisher and his wife Elizabeth. The latter became one of the heroes of the raid, saving her husband from death by concealing him under “an old dress and a piece of carpet.”

Elizabeth Fisher

"Having completed the work of death and devastation to their satisfaction, they loaded their arms and departed southwardly."

— John Speer, survivor

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 2

Corner of 11th & Mass

DIRECTIONSCorner of 11th & Mass

Near this corner, a squad of eleven raiders headed west to the top of Mount Oread to watch for signs of approaching Union troops. The main body—shouting "On to the Hotel!" and other battle cries—continued their ride down Massachusetts Street toward their main objective of the Eldridge House as smaller bands tracked along Vermont and New Hampshire Streets.

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 3

Black Recruits Camp

DIRECTIONSBlack Recruits Camp

In 1863, Lawrence was only heavily settled in the area that is now the 6th to 9th Street blocks along Massachusetts.

Downtown Lawrence in the 1860s

About one block south of the main town—at what is now the southwest corner of 10th and Massachusetts— stood an encampment of about 20 recruits for the 2nd Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment. As Quantrill's raiders entered Lawrence, the unarmed, ununiformed recruits heard the commotion and knew they were in danger. The men immediately fled toward the river along with other African American residents, but accounts vary as to whether most survived or fell in the massacre.

"A camp of colored recruits, I am told, located in the southern suburb, was early warned by the Lieutenant in charge, and, with one exception, escaped to the woods in safety. Later in the day they were numerous in the streets, hunting and bewailing their dead, and inquiring for some new city of refuge."

— James M. Winchell, survivor

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 4

White Encampment

DIRECTIONSWhite Encampment

A group of raiders led by George M. Todd rode through the camp on their way downtown, trampling the tents and killed 17 of the 21 unarmed, unprepared recruits. This was the first large group of residents to be attacked.

"When I heard the first shots I ran and climbed on a shed and saw the dust and a glimpse of them galloping in and shooting right and left. I ran to the tents and yelled, ‘Quantrell is here.’ We scattered... Before we crossed New Hampshire St. [three of us] were down.... I ran across an open lot to Joe Rawlins' back fence ... when we saw some of the gang ahead of us on Rhode Island St., I jumped the fence and turned to help Charley, when he was shot in the back and fell at my feet dead, leaving me the last of five."

— Cosma T. Colman, survivor

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 5

House Building

DIRECTIONSHouse Building

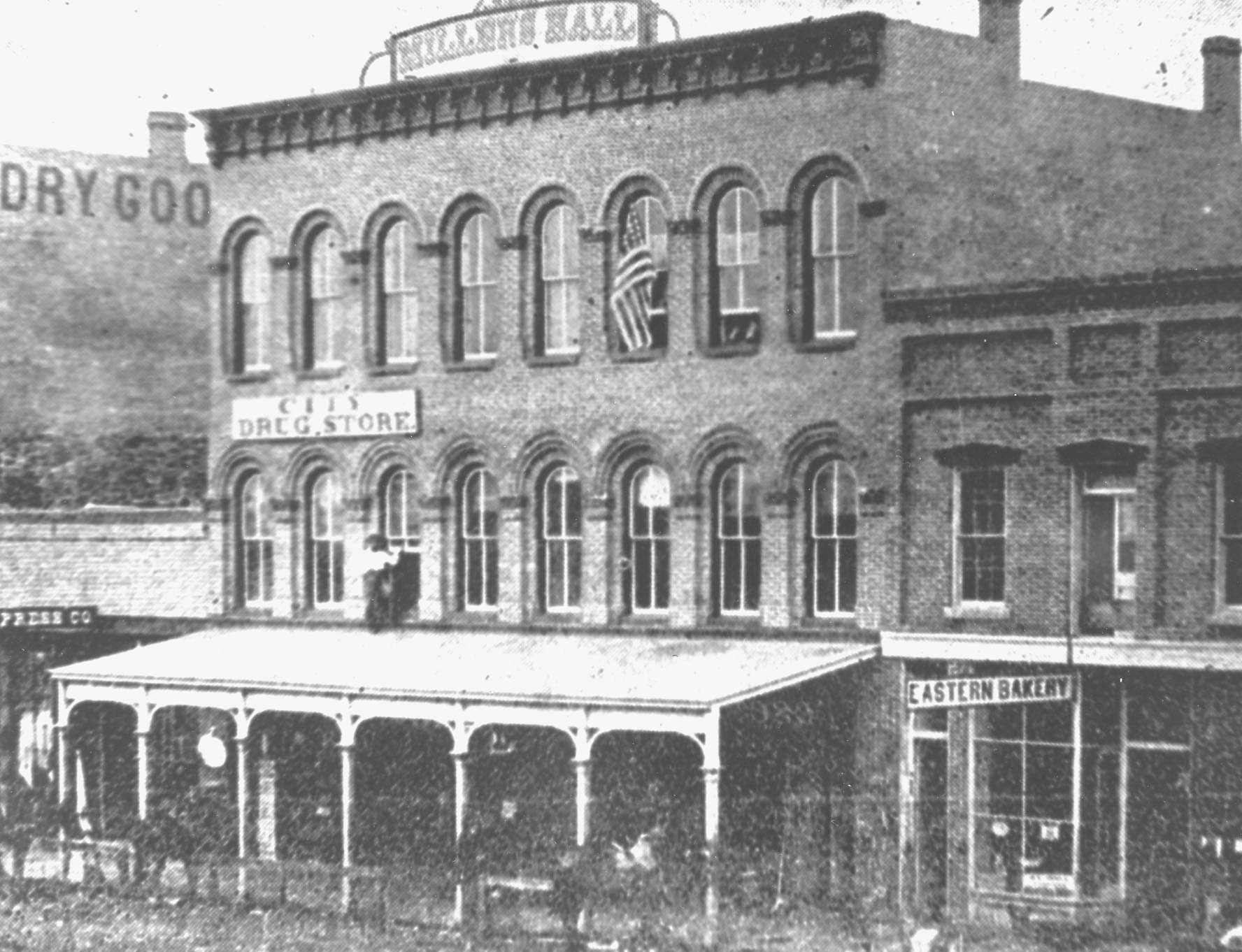

Individuals and groups of guerrillas stopped in homes and shops throughout the downtown area to loot, burn, and kill. Miller’s Hall (later renamed the House Building) was saved from destruction thanks to a store on the premise that was well stocked with clothing.

"They did not fire the building, but kept open doors during their stay. … The safe was opened and its contents appropriated, then the boys were set at work showing and doing up goods for their captors. When the demons had surfeited themselves with plunder, they deliberately and atrociously butchered these two helpless and inoffensive boys."

— Hovey E. Lowman, survivor

The House Building in later years, then called Miller's Hall

The two young clerks killed were James Perrine and James Eldridge. Out of four commercial buildings in town to survive the raid, only the House Building remains today.

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 6

Eldridge Hotel

DIRECTIONSEldridge Hotel

Then standing four stories tall, the Eldridge House hotel was the largest building in town, a prominent gathering place, and Quantrill’s main tactical objective. Capturing the hotel would prevent organized resistance from townspeople.

The Eldridge Hotel in later years

Raiders quickly converged on the Eldridge, prompting Union Captain Alexander R. Banks, the Provost Marshal of Kansas, to hang a white bedsheet out a window signifying surrender.

"We were in the company of about 50 or 60 men and women surrounded in the Eldridge House and had three alternatives: to endeavor to fight without arms, to try and escape and run the risk of being shot as we ran, or to surrender. I adopted the latter and obtained the assurance that we would be protected."

— Captain Alexander R. Banks

The bushwhackers looted valuables from the hotel residents and burned down the structure, refusing to allow black cook Peter Jones to save his child from the fire. However, Quantrill allowed a group of hotel patrons to be spared and moved to the City Hotel down the street.

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 7

Ravine

DIRECTIONSRavine

Before it was filled in and became a city park, this area was a wooded ravine that separated downtown from West Lawrence. With steep banks and a single bridge spanning it, the ravine served as a hiding place for Lawrencians during the raid.

The ravine that separated downtown from West Lawrence

While some of Quantrill's men rode along the edge of the ravine shooting at fleeing townspeople, a small group crossed the bridge to hunt for prominent residents of West Lawrence. Guerrillas looted and burned homes and killed several men there, but many others--including Senator James H. Lane--used cornfields and hilly terrain to avoid discovery.

"From the upper hall and windows [of the Eldridge House] could be seen squads of riders dashing around from point to point, seemingly in a mad chase after game, with fugitives in a race for life, making for the brushy ravines…"

— Robert G. Elliott, survivor

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 8

Dix Home

DIRECTIONSDix Home

The fate of the Dix family and their neighbors could represent numerous tragic stories during Quantrill’s Raid.

Ralph (R. C.) and Jetta Dix lived in a three-story home at what is now 717 Vermont Street, site of the park next to the Lawrence Public Library. To their north was a blacksmith shop that they ran in conjunction with their carriage shop, while the Johnson House hotel (a former meeting place for pro-Union "Red Legs") neighbored the Dixes on the other side.

Ralph (R. C.) and Jetta Dix lived in a three-story home at what is now 717 Vermont Street, site of the park next to the Lawrence Public Library. To their north was a blacksmith shop that they ran in conjunction with their carriage shop, while the Johnson House hotel (a former meeting place for pro-Union "Red Legs") neighbored the Dixes on the other side.

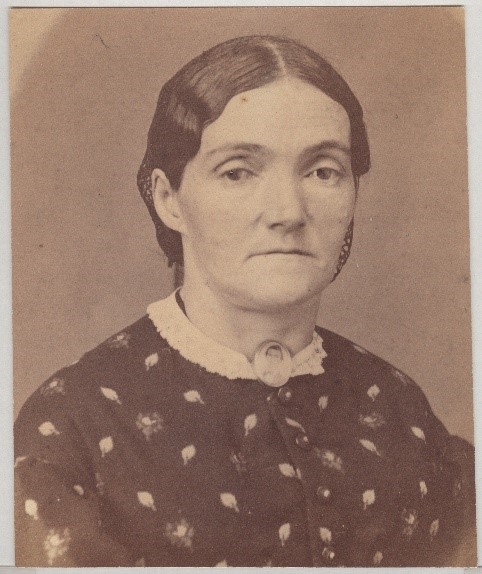

Jetta Dix in later years

As soon as she realized that Lawrence was under attack, Jetta woke up her household and got her husband, children, and maid outside. Jetta’s brother-in-law Stephen Dix was shot in the head and died in her arms. Ralph fell in with a group of men whom the raiders placed under guard outside the hotel.

Guerrillas torched the Johnson House and the collapse of this structure set the Dix residence ablaze. After her husband was killed, Jetta searched for her children and found them hiding in the ravine with the family maid, a black woman named Phoebe. Jetta and her children survived to rebuild their home in 1864.

Guerrillas torched the Johnson House and the collapse of this structure set the Dix residence ablaze. After her husband was killed, Jetta searched for her children and found them hiding in the ravine with the family maid, a black woman named Phoebe. Jetta and her children survived to rebuild their home in 1864.

"At the Johnson House they shot all that showed themselves … Such was the common fate of those who surrendered themselves as prisoners. Mr. R. C. Dix was one of them."

— Rev. Richard Cordley, Lawrence resident

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 9

Methodist Church Makeshift Morgue

DIRECTIONSMethodist Church Makeshift Morgue

This church was constructed in 1889-90. In 1863, the First Methodist congregation met in a church at what is now 724 Vermont, across from the site of the Dix home.

After the raid, the church became a makeshift morgue, where survivors brought the dead and laid them out for identification.

After the raid, the church became a makeshift morgue, where survivors brought the dead and laid them out for identification.

"I met many of the dead being carried into our shops and into the old Methodist Church. Both places were turned into morgues. Mr. Dix’s body was carried into one of our shops…"

— Jetta Dix, survivor

The Methodist Church on its original site across from the Dix home

"We went to the Methodist Church where there were two rows of dead, twenty or thirty with faces covered, we lifted the covering from each and I recognized most of them but neither we sought were there. It was dreadful seeing wives and mothers when they discovered the dead."

— Louisa B. Prentiss, survivor

Previous slide

Next slide

Stop 10

Watkins Museum of History

DIRECTIONSWatkins Museum of History

Your last stop is the Watkins Building, which was constructed in 1886-88. At the time of Quantrill’s Raid, this was the site of the Wesley H. Duncan home. Duncan saved himself and his house after giving the raiders keys to his downtown store.

After four hours of destruction, Quantrill’s scouts warned him of approaching Union troops. The guerrilla chieftain reassembled his men east of South Park and they escaped out of town, riding south on Tennessee Street.

After four hours of destruction, Quantrill’s scouts warned him of approaching Union troops. The guerrilla chieftain reassembled his men east of South Park and they escaped out of town, riding south on Tennessee Street.

"[W]ithin two blocks there were several charred bodies lying on or near the sidewalk, where they had been shot down and afterwards partly burned. The walls of the burning buildings had nearly all fallen, but the fires were still burning on the sides of the street, making the heat so intense that it was almost impossible to pass along the street. I stood in front of our store for a moment, almost dazed by the terrible destruction."

— Peter D. Ridenour, survivor

This engraving published soon after the raid shows the destroyed Eldridge House in the forground, with the Methodist Church just behind it.

Quantrill and his men left devastation in their wake. Around 200 men and boys had been killed, 80 women were widowed, and 250 children left fatherless. Nearly every home and business in the main part of town had been destroyed and about $2 million (in 1863 dollars) of property lost.

Grave in Pioneer Cemetery for a young victim of Quantrill's Raid

The effects of Quantrill’s Raid (also known as the Lawrence Massacre) rippled outward. In response to this attack on civilians, Union officers in Missouri issued Order No. 11, which authorized removal of those deemed Confederate sympathizers. The savage guerrilla war along the border lasted until 1865.

In Lawrence, survivors and their friends around the country showed an indomitable spirit, throwing themselves into the task of rebuilding their homes and livelihoods. The town soon thrived as never before, but residents never forgot the horror of August 21, 1863.

In Lawrence, survivors and their friends around the country showed an indomitable spirit, throwing themselves into the task of rebuilding their homes and livelihoods. The town soon thrived as never before, but residents never forgot the horror of August 21, 1863.

"Lawrence has been stunned by the blow, but not killed. We feel confident she will rise from her ashes stronger than ever."

— Rev. Richard Cordley

Previous slide

Next slide

The tour you have taken is necessarily brief, giving basic details and a few personal stories of the raid. We encourage you to gain a fuller picture by visiting the Watkins Museum, headquarters of the Douglas County Historical Society. The Watkins is open Tuesdays through Saturdays, with free admission.

Other Related Sites

Oak Hill Cemetery

DIRECTIONSServes as the final resting place for many victims of Quantrill’s Raid. Also contains the Citizens Monument erected in 1895 to commemorate those lost.

Other Related Sites

Pioneer Cemetery

DIRECTIONSThe original burying ground for victims of the raid, some of whom remain there.

Other Related Sites

Ground marker - 601 W 7th Street

DIRECTIONSThis small stone marker near the alley entrance on the south side of the street marks the location where raiders shot four prominent citizens.

Other Related Sites

800 block of Massachusetts Street

DIRECTIONSWalk through the alleyway behind the east side of this block and you will clearly see old stonework on many buildings—evidence of efforts to rebuild after the raid with fire-resistant material.

Previous slide

Next slide