TOPEKA, KANSAS:

FROM BROWN TO BROWN

Use this arrow to learn more at each stop.

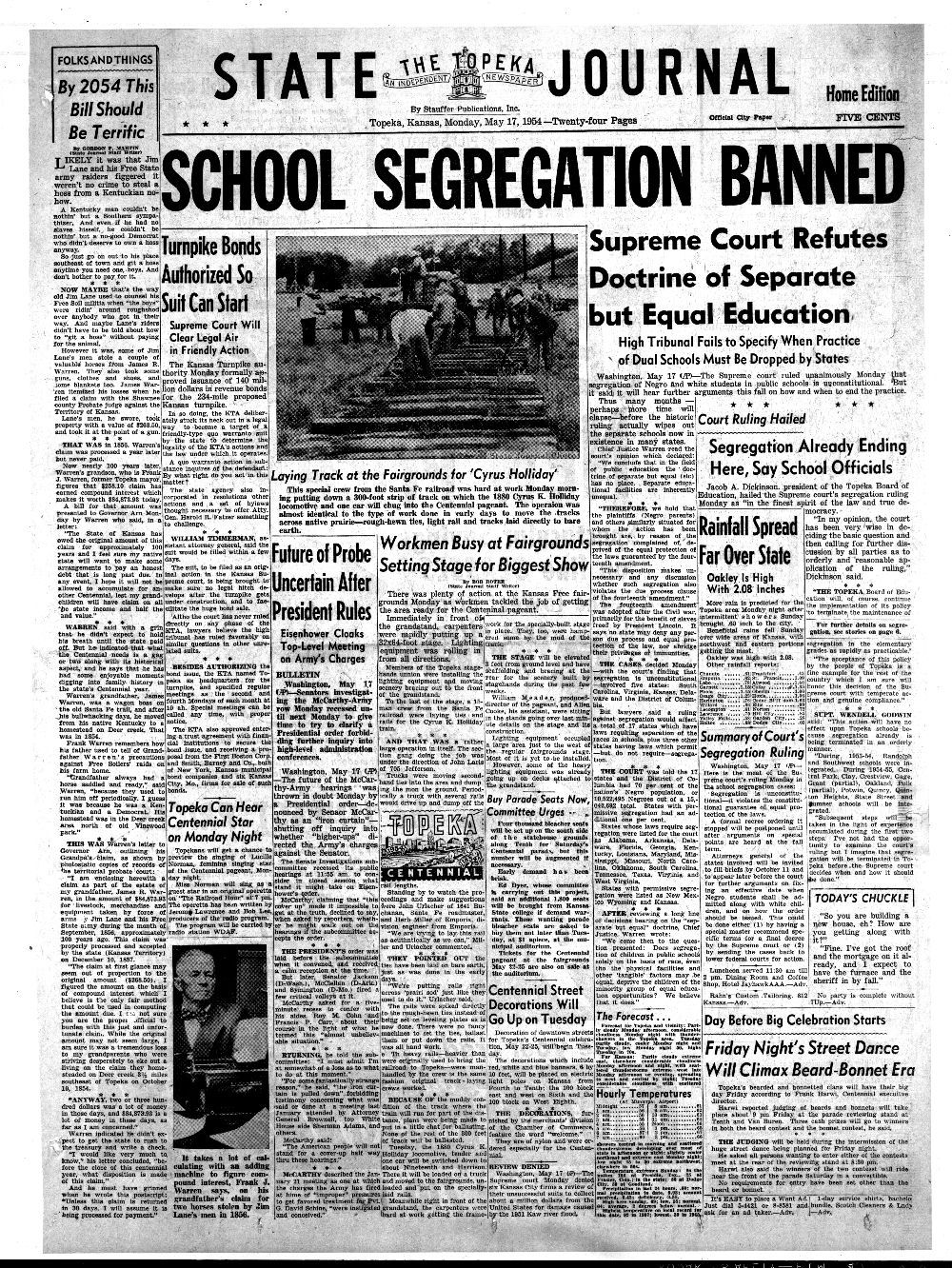

As America entered the 1950s, school segregation was required by law in 17 states, Washington, D.C., and countless other jurisdictions. All of these embraced the “separate but equal” doctrine declared by the United States Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). Thurgood Marshall, lead counsel for the NAACP, rose to attack legal segregation head-on in the first of five lawsuits that would reach the Supreme Court and be argued together as Brown v. Board of Education. On May 17, 1954, the Court ruled that “In the field of public education, the doctrine of “separate but equal” has no place. Possibly no action taken by any of the three branches of government has changed the social fabric of the nation more dramatically than this ruling. Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site was established in 1992 to preserve and interpret the story of that case, and to commemorate one of the most transformative legal rulings in United States History.

Brown v. Board of Education was actually a culmination of 5 cases dealing with school desegregation. The four other cases were as follows:

Belton v. Gebhart (Delaware, 1951): This case dealt with school facilities being highly unequal between black and white schools in that district. Segregated schools were often too far away for black students to reasonably travel to and attend. In addition, no busing was available to black students.

Bolling v. Sharpe (Washington, D.C., 1954): This case dealt with a newly opened school in Washington, D.C. that refused to admit black students. The plaintiffs in this case argued that segregation violated the equal rights of those black students.

Briggs v. Elliott (Clarendon County, South Carolina, 1952): This case involved the issue of unequal and inadequate facilities for black students. In addition, no busing for black students existed in this district.

Davis v. County School Board (Prince Edward County, Virginia, 1952): This case dealt with unequal resources and poor school conditions for black students. This case was unique in that the fight for equality was led largely by a group of students. High school student Barbara Johns and hundreds of other students organized a two-week student protest to argue for better schools and equal funding.

Bolling v. Sharpe (Washington, D.C., 1954): This case dealt with a newly opened school in Washington, D.C. that refused to admit black students. The plaintiffs in this case argued that segregation violated the equal rights of those black students.

Briggs v. Elliott (Clarendon County, South Carolina, 1952): This case involved the issue of unequal and inadequate facilities for black students. In addition, no busing for black students existed in this district.

Davis v. County School Board (Prince Edward County, Virginia, 1952): This case dealt with unequal resources and poor school conditions for black students. This case was unique in that the fight for equality was led largely by a group of students. High school student Barbara Johns and hundreds of other students organized a two-week student protest to argue for better schools and equal funding.

At the heart of these cases was the issue of equal protection under the law. Ultimately, Brown made racial segregation in the field of public education illegal, thus securing equal protection of the law for black children.

The Plaintiffs in the Brown v. Board of Education case were made up of 13 Topeka families.

Oliver Leon Brown

Mrs. Darlene Brown

Mrs. Lena M. Carper

Mrs. Sadie Emmanuel

Mrs. Marguerite Emmerson

Mrs. Shirla Fleming

Mrs. Andrew (Zelma) Henderson

Mrs. Shirley Hodison

Mrs. Richard (Maude) Lawton

Mrs. Alma Lewis

Mrs. Iona Richardson

Mrs. Vivian Scales

Mrs. Lucinda Todd

Oliver Leon Brown

Mrs. Darlene Brown

Mrs. Lena M. Carper

Mrs. Sadie Emmanuel

Mrs. Marguerite Emmerson

Mrs. Shirla Fleming

Mrs. Andrew (Zelma) Henderson

Mrs. Shirley Hodison

Mrs. Richard (Maude) Lawton

Mrs. Alma Lewis

Mrs. Iona Richardson

Mrs. Vivian Scales

Mrs. Lucinda Todd

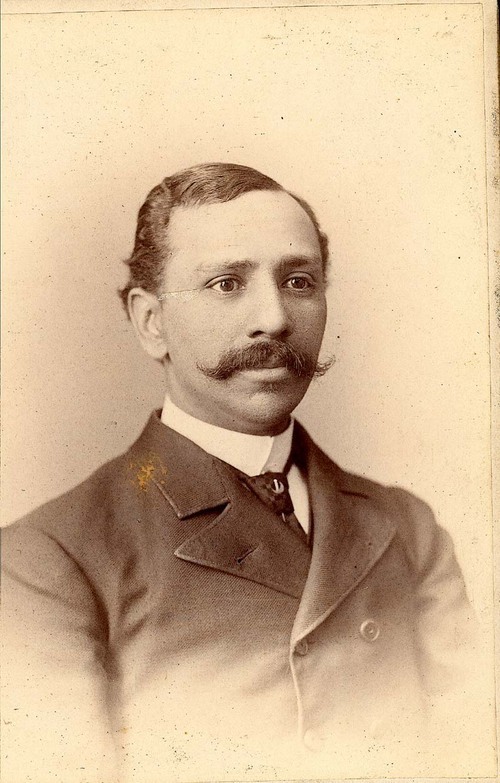

Oliver Brown

Alvin and Lucinda Todd family

Zelma Henderson

At the time of the Brown case in the early 1950s, four all-Black schools served Topeka’s Black community.

It was often difficult for Black families to get their children to school every morning in a timely manner due to the distance many children had to travel to a segregated facility.

It was often difficult for Black families to get their children to school every morning in a timely manner due to the distance many children had to travel to a segregated facility.

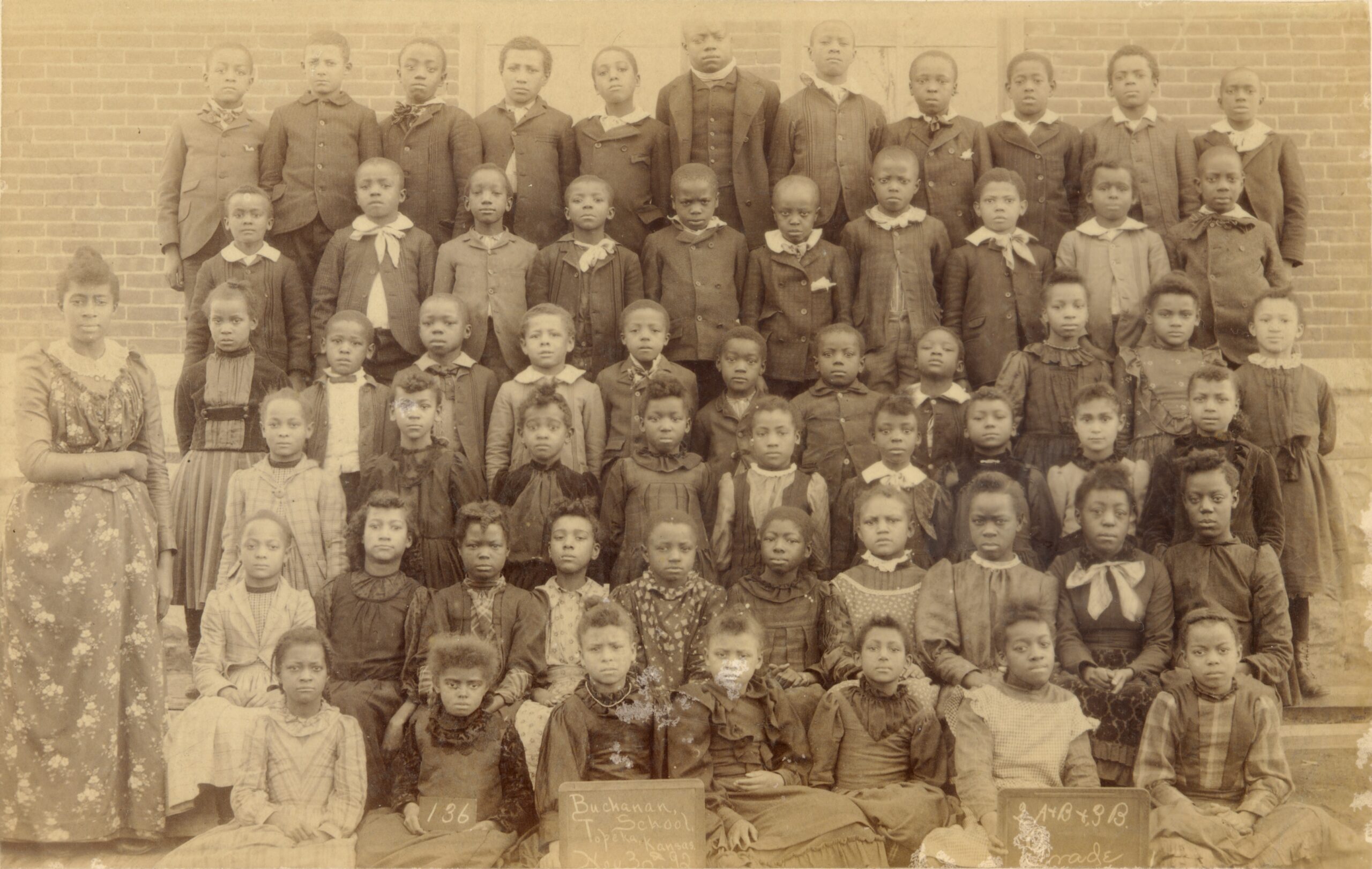

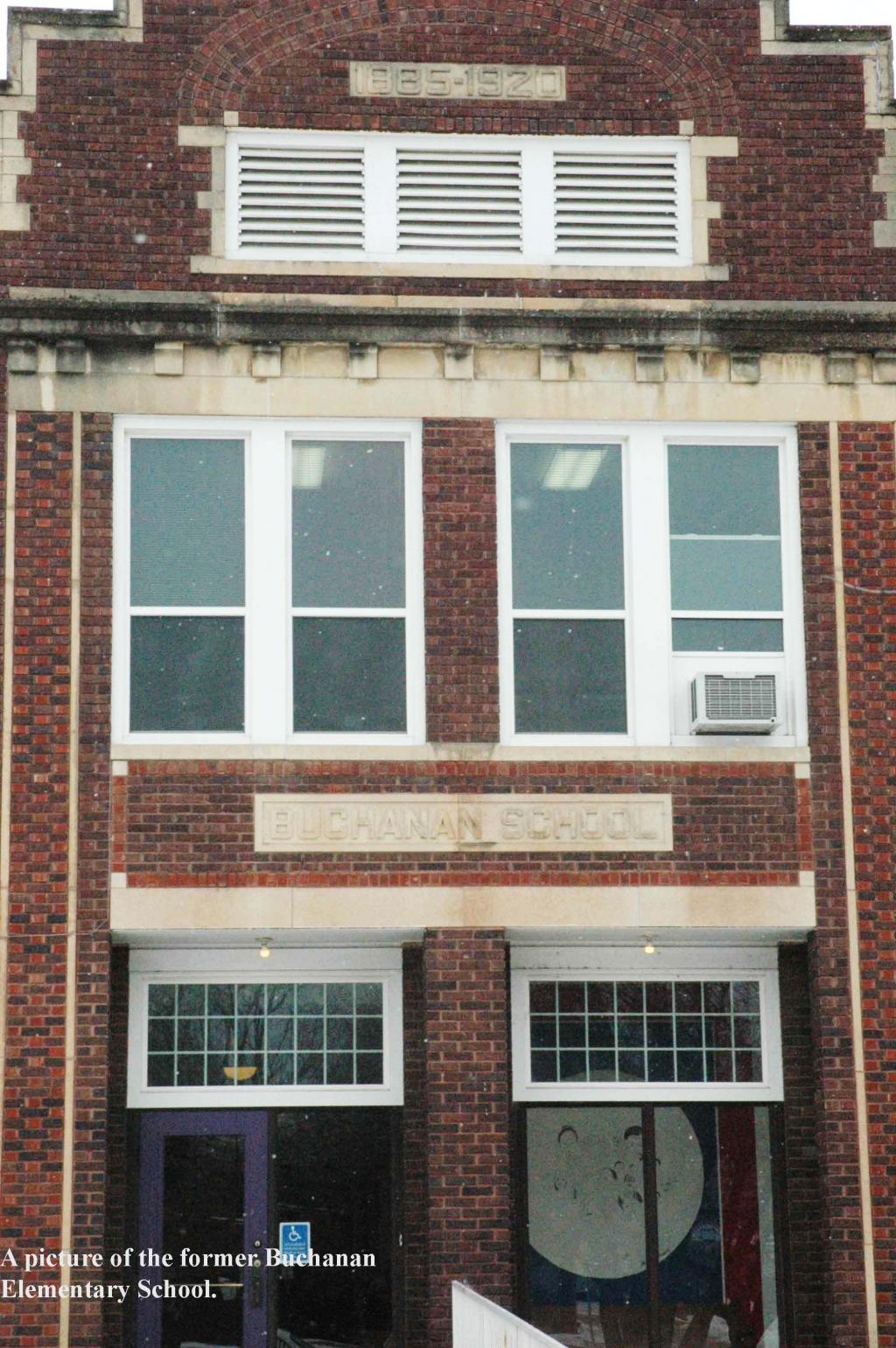

Buchanan School, 1885

Charles Clinkscale, 5th grade class, Buchanan School

Julia B. Abbott, 2nd grade class, Buchanan School

In the early 1950s, Topeka was home to 18 schools for White children.

This afforded White families more convenience when it came to finding a close neighborhood school for their children.

This afforded White families more convenience when it came to finding a close neighborhood school for their children.

New Gage Park School

Central Park Kindergarten, 1928

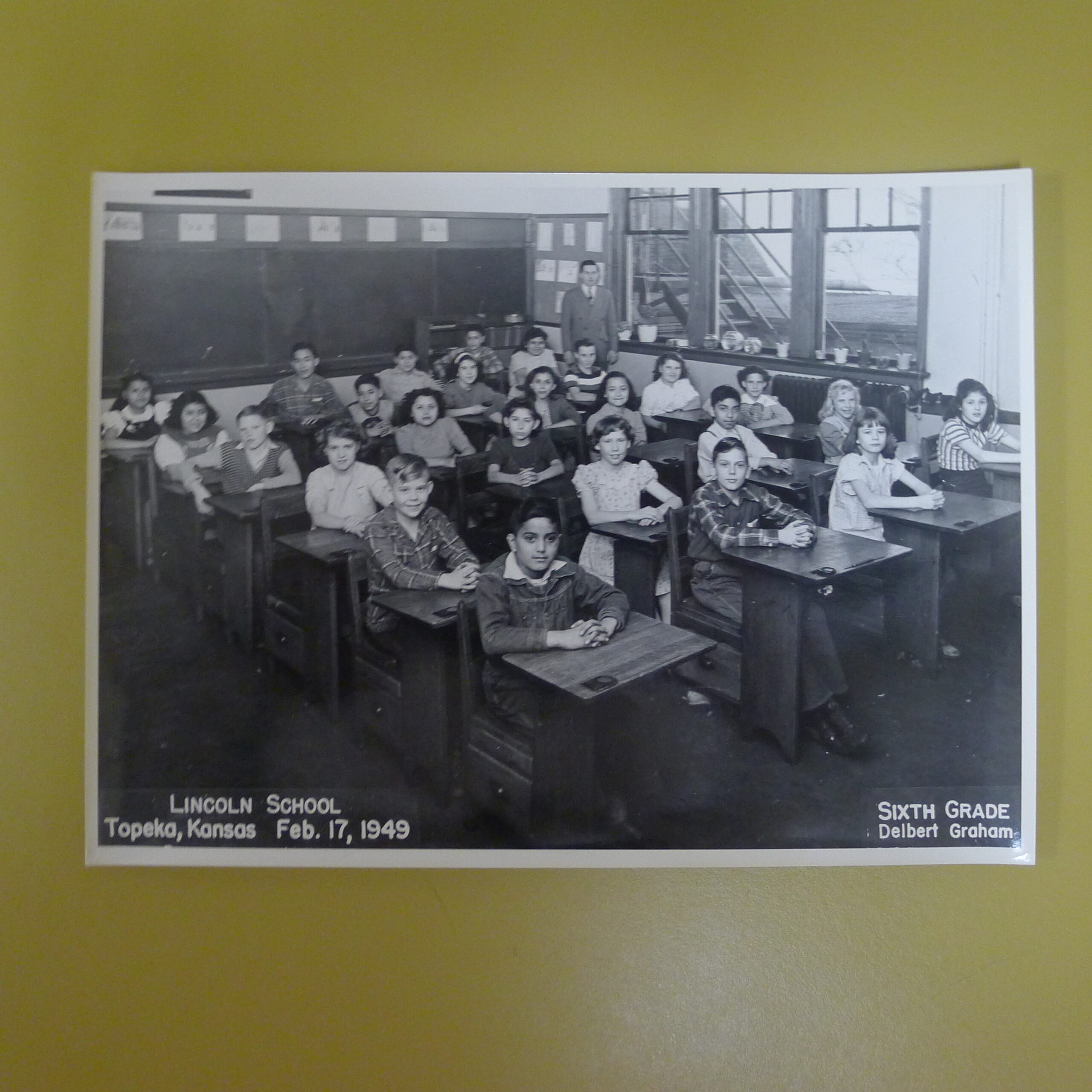

Lincoln School, 6th grade, 1949

By the early 1880s, Topeka’s Board of Education voted to “employ no more White teachers in colored schools.” With only Black teachers in the Black schools, the Board believed that Black teachers would be better able to connect with Black students. The Board believed that Black teachers “Can do more for their race than white teachers.”

African-American teachers, 1949

Fred Roundtree

Scroll down to continue.

Stop 1

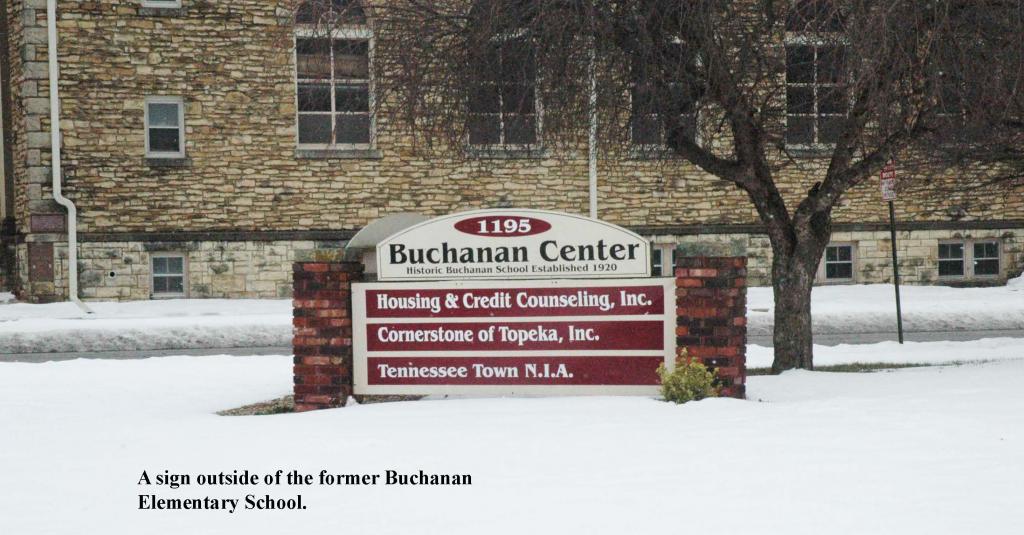

Buchanan Elementary

1195 SW Buchanan St. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSBuchanan Elementary

1195 SW Buchanan St. Topeka, KS

By the time the Brown v. Board of Education case was filed in 1951, Buchanan was one of four elementary schools established for Topeka’s African American children, along with Monroe, McKinley, and Washington.

Built in 1885, Buchanan became the cornerstone of the Tennessee Town community, a section of Topeka largely settled by former enslaved people fleeing the South in the late 1870s and early 1880s. In 1910, the school became the home for the kindergarten started in 1893 by Rev. Charles Sheldon in the nearby Central Congregational Church.

The school was the first kindergarten for African American children west of the Mississippi. In 1920, Buchanan was remodeled, then enlarged from 4 to 8 classrooms, and continued to help accommodate students until the school was closed in the late 1950s.

Stop 2

Charles Curtis House Museum

1101 SW Topeka Blvd. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSCharles Curtis House Museum

1101 SW Topeka Blvd. Topeka, KS

By the time the Brown v. Board of Education case was filed in 1951, Buchanan was one of four elementary schools established for Topeka’s African American children, along with Monroe, McKinley, and Washington.

Built in 1885, Buchanan became the cornerstone of the Tennessee Town community, a section of Topeka largely settled by former enslaved people fleeing the South in the late 1870s and early 1880s. In 1910, the school became the home for the kindergarten started in 1893 by Rev. Charles Sheldon in the nearby Central Congregational Church.

The school was the first kindergarten for African American children west of the Mississippi. In 1920, Buchanan was remodeled, then enlarged from 4 to 8 classrooms, and continued to help accommodate students until the school was closed in the late 1950s.

Stop 3

Constitution Hall

429 S Kansas Ave. #427 Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSConstitution Hall

429 S Kansas Ave. #427 Topeka, KS

The Topeka Constitution, the first of four constitutions in Kansas attempting to determine whether the territory would enter the Union free or slave, declared, “There shall be no slavery in this state.”

Beginning on October 23, 1855, and continuing for three weeks, 47 delegates from across the territory gathered in this building, ever after known as Constitution Hall, to draw up a Constitution and elect a governor. This constitution however was blocked by the southern controlled senate. In defiance of the order of President Franklin Pierce to peacefully retire, the Free State legislature met again on July 4, 1856. Four hundred federal troops on horseback thundered down Kansas Avenue and dispersed the legislature. However, Constitution Hall remained a hub of Free State activity. It served as a meeting hall and a warehouse for supplies and wagons supplied by northern sympathizers to arm the Free State Militia. The Topeka Guard, formed to protect the Free State settlers, used the building as their headquarters.

The question of whether Kansas would enter the union free or slave, was finally decided in 1859, when the Wyandotte Constitution was ratified by the United States Congress on January 29, 1861. Kansas finally entered the Union, free of slavery.

Stop 4

First Washburn University School of Law

118 SW 8th Ave. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSFirst Washburn University School of Law

118 SW 8th Ave. Topeka, KS

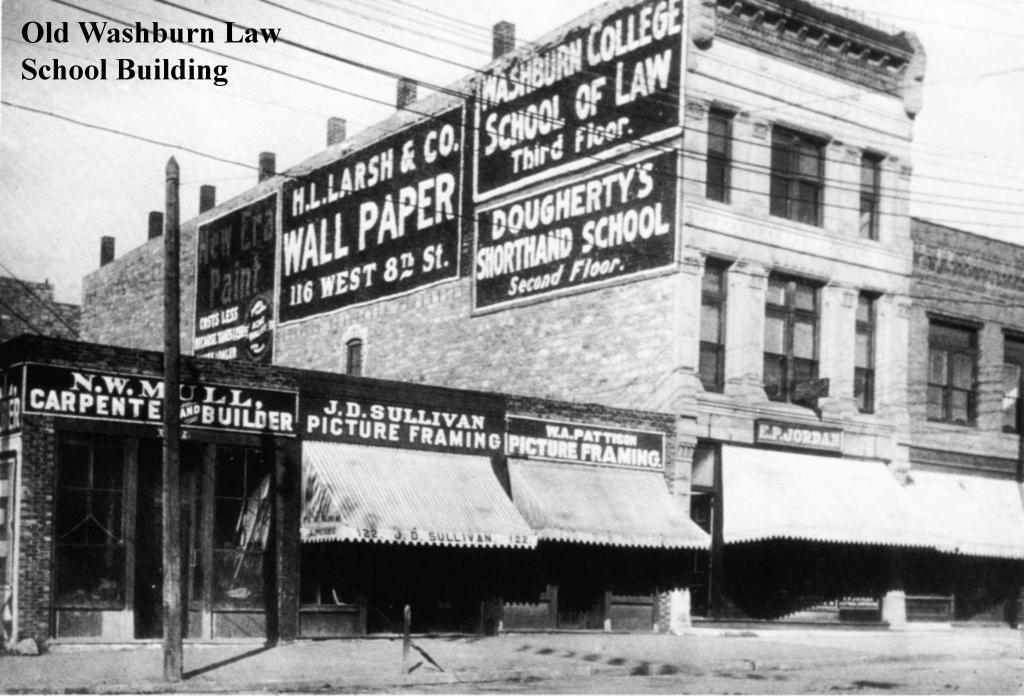

In 1951 Washburn Law alumni found themselves on both sides of Brown v. Board of Education. Washburn College was established in 1857, when members of Topeka’s First Congregational Church decided the city needed a college, and on February 6, 1865, Lincoln College was incorporated. In 1868, the name of the school was changed to Washburn in honor of Ichabod Washburn, a Massachusetts industrialist who donated $25,000 to help support the college. In 1903, a school of law was established on the 3rd floor of the dry goods building located on west 8th street. Staff of the new law school consisted of just one full-time professor and 23 practicing attorneys serving as part time faculty. Forty students paid $50 a year to attend classes.

The building continued to house the law school until 1911, when the school was moved to another downtown building. At a time when just gaining entrance to a law school was a battle for women and minorities, Washburn pioneered the entrance of African Americans and women into the legal field. The first African American graduated in 1910, and the first woman in 1912.

Stop 5

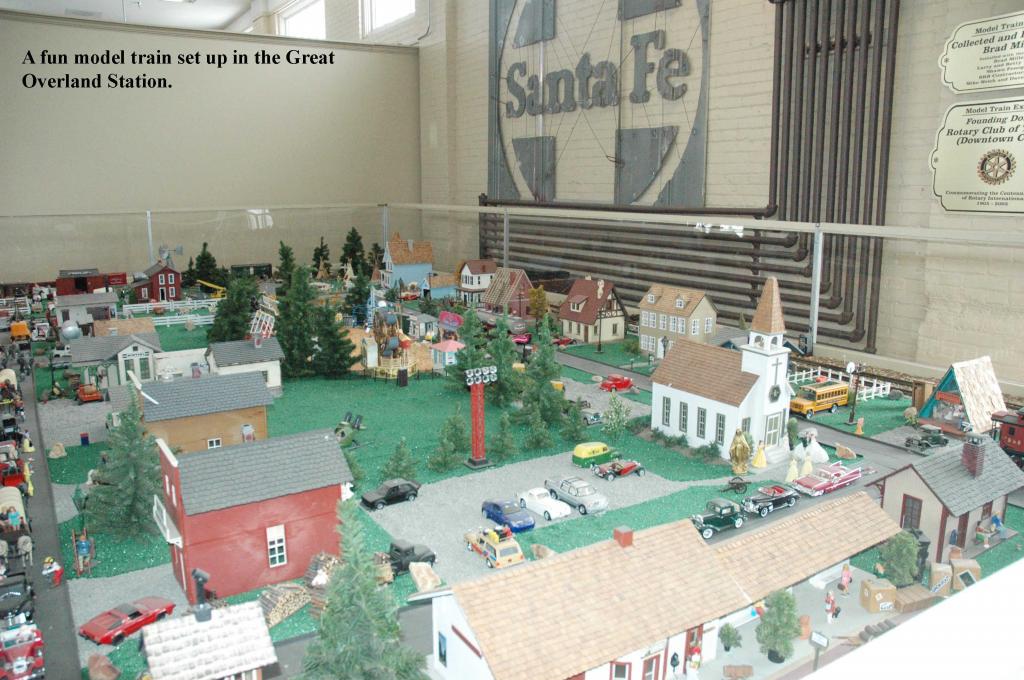

Great Overland Station

701 N Kansas Ave. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSGreat Overland Station

701 N Kansas Ave. Topeka, KS

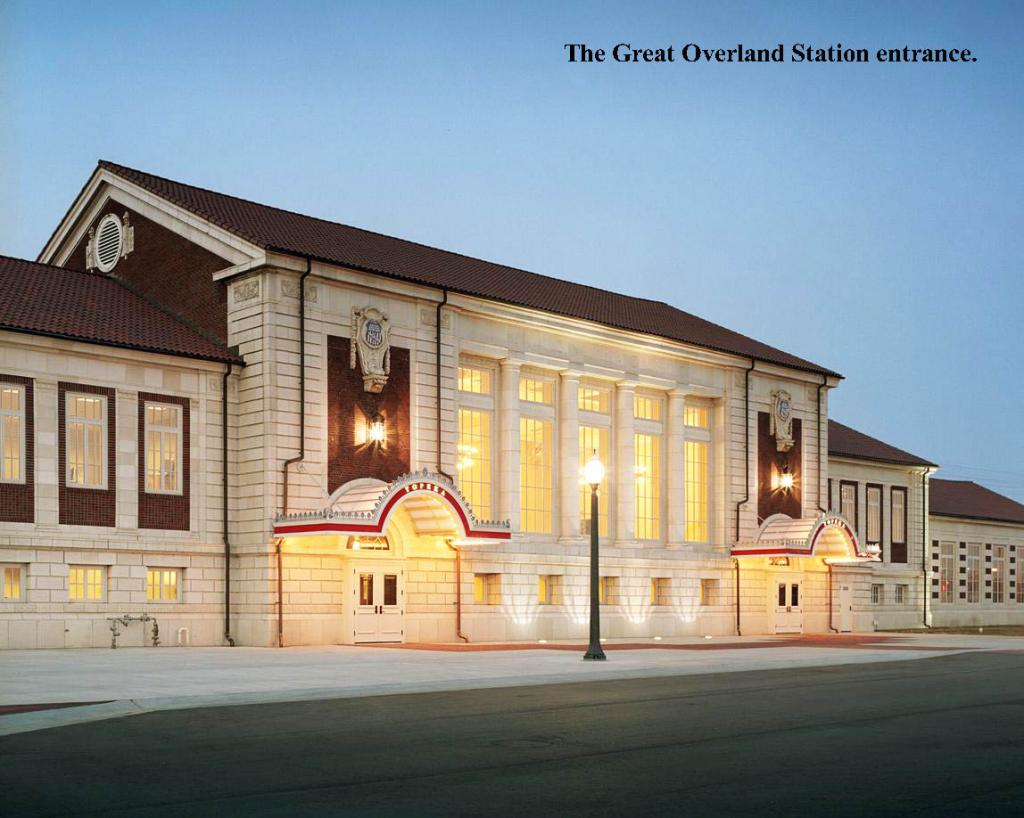

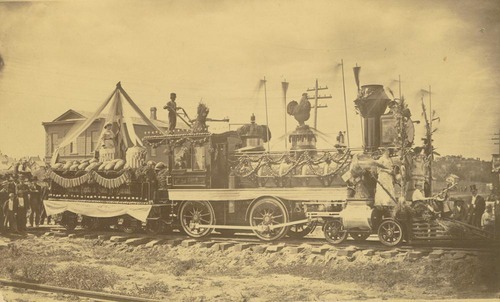

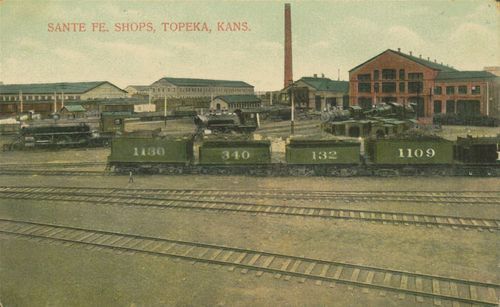

By the late 1860s, Topeka was a bustling hub for the railroad. Miles of track connected cities and towns in the state and throughout the nation. Railroads crisscrossed the state, bringing with them a flood of immigrants and goods.

Just after the Civil War, African American refugees from the South arrived in Topeka and began settling in the area and other parts of Kansas. These refugees became known as Exodusters. A group of these refugees settled in Nicodemus, Kansas, which became the first African American settlement west of the Mississippi. By World War I, roughly 1,850 train depots dotted the Kansas landscape. Built as a passenger station for the Union Pacific in 1927, the Great Overland Station was described as one of the finest on the line. The last passenger train left the Station on May 2, 1971. The building continued to serve as railroad offices until 1988, when it was abandoned.

Adjacent to historic North Topeka, the station today houses a railroad museum that bring the people and stories of an earlier time back to life.

Stop 6

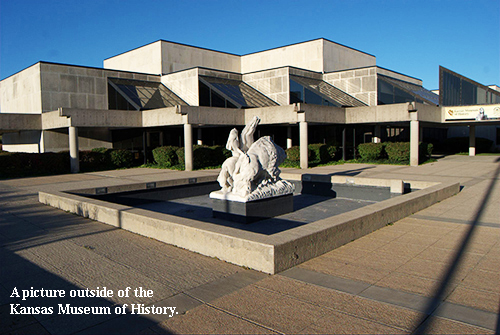

Kansas Museum of History

6425 SW 6th Ave. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSKansas Museum of History

6425 SW 6th Ave. Topeka, KS

The Kansas Museum of History and Kansas Historical Society Complex sits on the western edge of Topeka and is surrounded by 81 acres of Kansas grasses and woodlands. The Kansas Historical Society was founded in 1875 and serves as the state’s trustee for preserving the stories of people, places, and events that come together in a vibrant history.

The Kansas Museum of History brings together these stories ranging from the Native Americans who roamed the Tallgrass Prairie, to the fight over whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state, to the birth and impact of the fast food industry. Exhibits range from a Cheyenne tipi to a covered wagon ready for its trip across the Oregon Trail, to an 1880 steam locomotive, and even a 1950s diner. The vision of this museum and the historical society remains to enrich people’s lives by connecting them to the past.

Stop 7

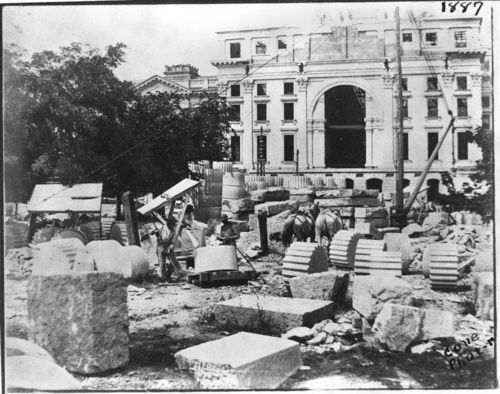

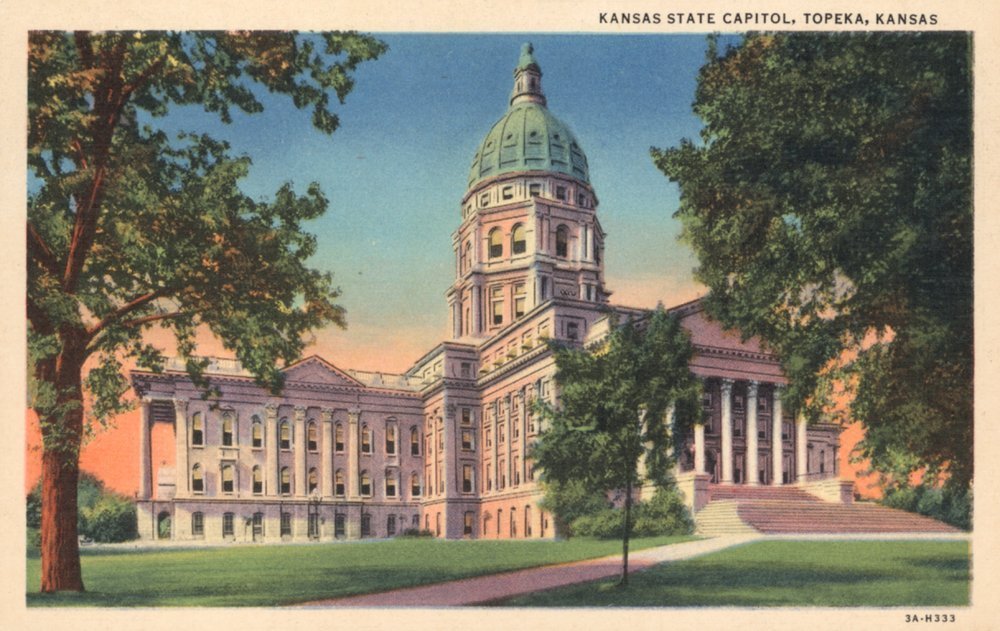

Kansas Statehouse

300 SW 10th St. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSKansas Statehouse

300 SW 10th St. Topeka, KS

Construction of the Kansas Statehouse began in October 1866, with the legislature first taking their seats in the unfinished East wing in 1870. Work continued on the building throughout the next three decades, finally being completed in 1903.

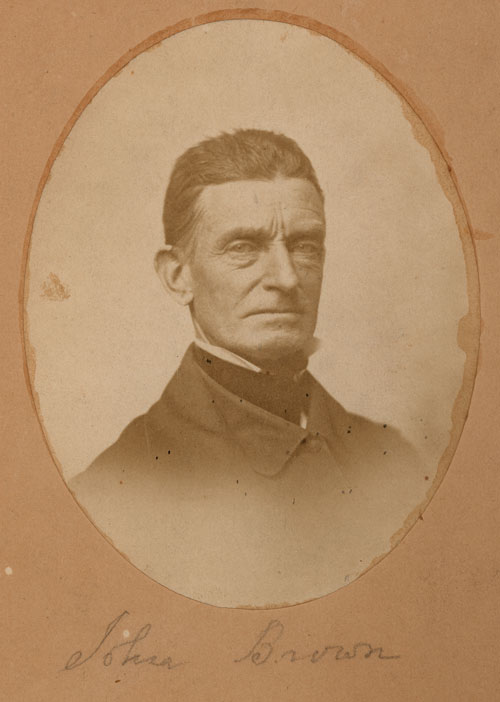

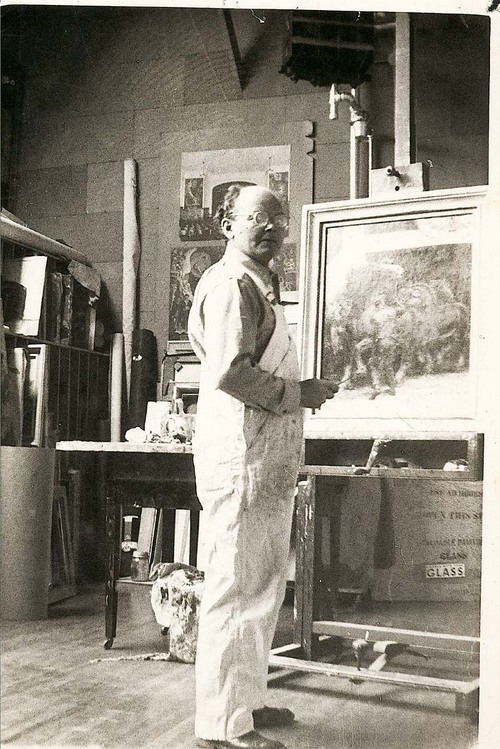

In 1937 a Kansas born artist, John Steuart Curry, was selected to portray the state’s story in murals on the second floor. A centerpiece of the project was titled Tragic Prelude. Here, Curry created an image of John Brown that remains one of the most recognized depictions of the abolitionist in the world.

Curry’s mural shows Brown in all of his fury, with arms outstretched, holding a Bible in one bloodied hand and a Sharps rifle in the other, as a twister and prairie fire rage behind him.

Stop 8

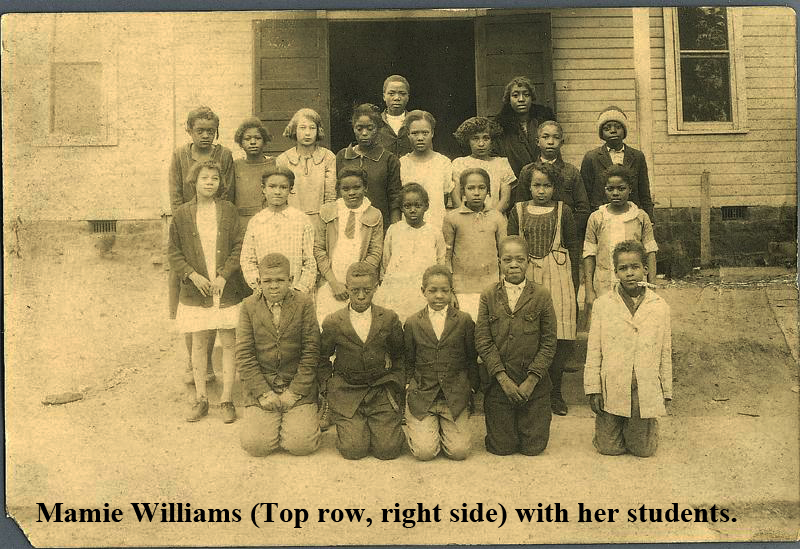

Mamie Williams House

1503 SE Quincy St. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSMamie Williams House

1503 SE Quincy St. Topeka, KS

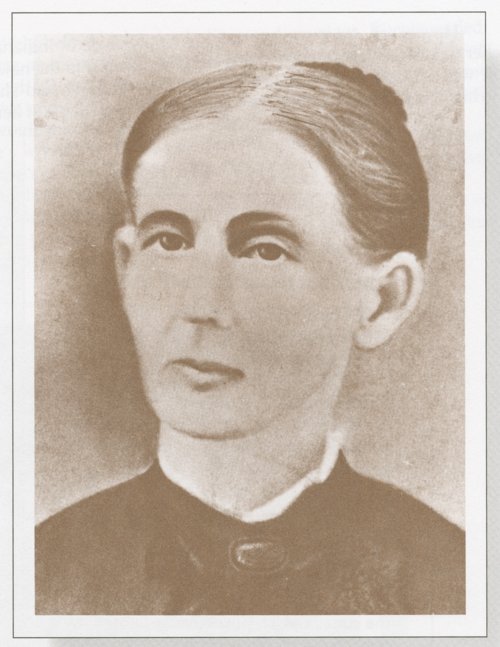

Mamie Luella Williams was a lifelong educator in Topeka, Kansas. She was born in 1894 in Greenwood, South Carolina. Five years later she moved with her family to Topeka, where she would become an accomplished teacher and principal at some of the segregated schools. Miss Williams was the only African American in her graduating class at Washburn University, and went on to spend 4 summers at Columbia University in New York, where she earned advanced certificates. Miss Williams chose to be a career educator, as she taught at a time when women had to choose between their career as educators, or forfeiting teaching in order to have families.

After retiring from teaching, Miss Williams continued to play an active role in her community. In addition, she served as a delegate to the White House Conference on Aging in 1971. In 1976 she was featured in a documentary titled, "75 Years on Quincy Street," where she talked about her career and life in Topeka.

Located two blocks from the former Monroe Elementary School is the Williams Science and Fine Arts Magnet School, named in honor of Miss Williams.

Stop 9

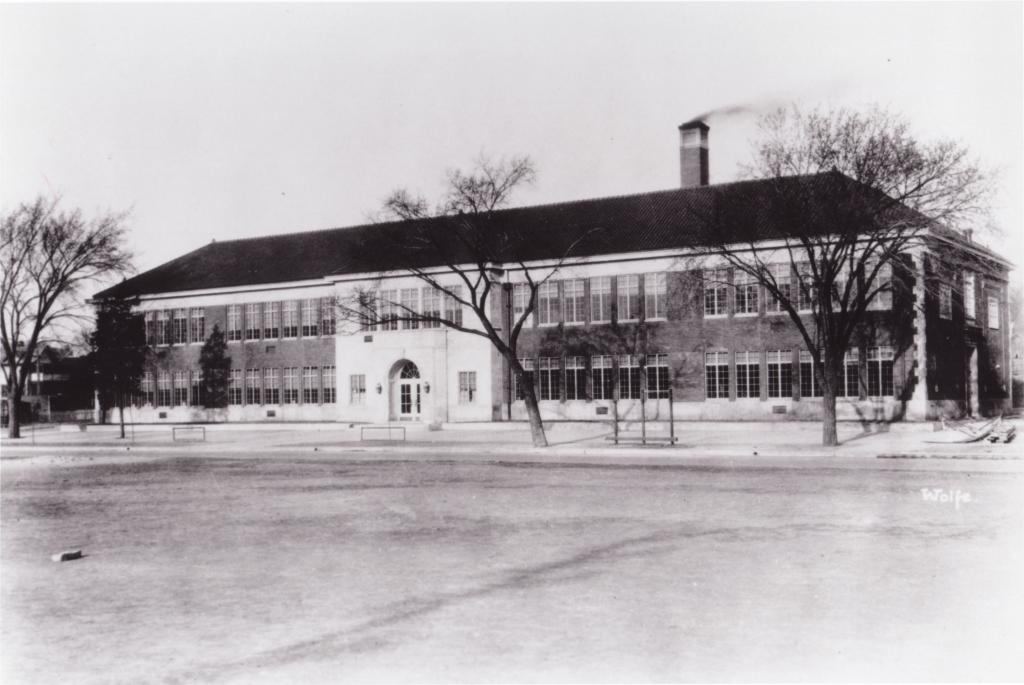

Monroe Elementary

1515 SE Monroe St. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSMonroe Elementary

1515 SE Monroe St. Topeka, KS

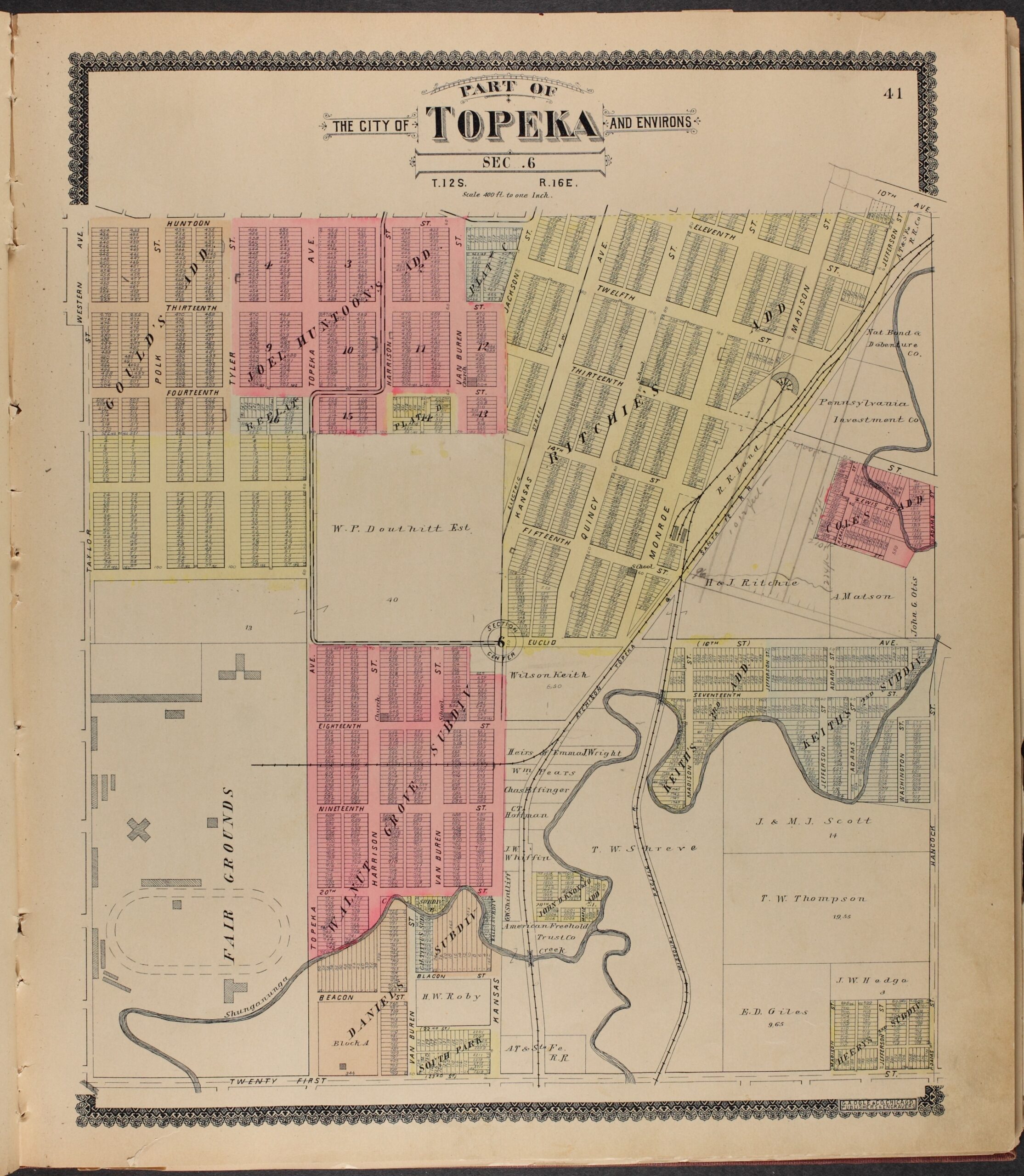

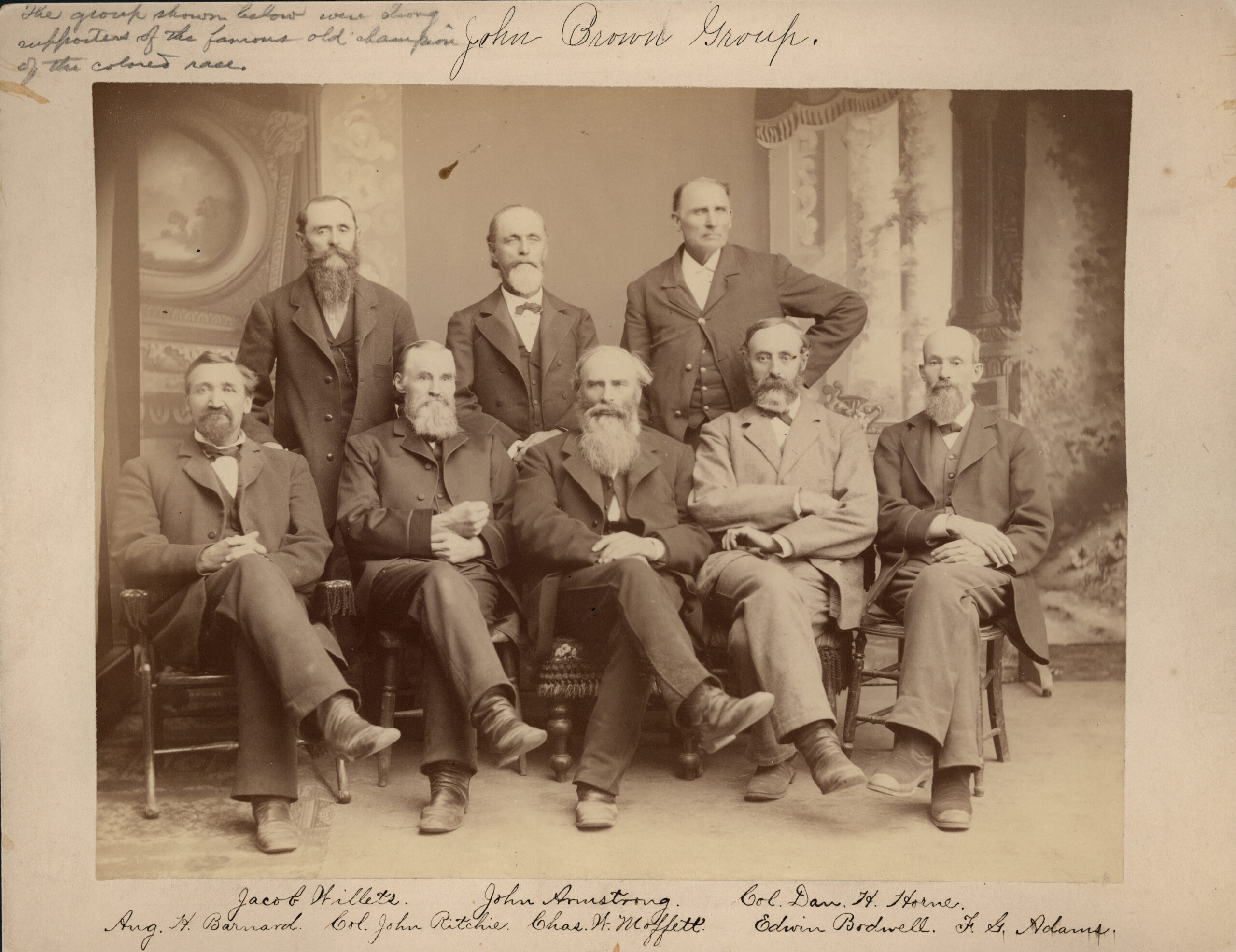

Monroe Elementary was built in 1926 as an all-black elementary school. For nearly 30 years, it served hundreds of children from one of Topeka’s black communities located in the Ritchie Addition neighborhood, named after the Topeka abolitionist John Ritchie (1817-1887).

After the court case, Monroe slowly began to see more diversity in its classrooms. As the surrounding neighborhood’s demographics began to shift and change, so too, did Monroe School.

In 1975 the school closed, as newer, bigger schools were being built for Topeka’s children. After being used as a district warehouse and storage facility, Monroe sat abandoned for a number of years. In the early 1990s, the federal government purchased the facility and grounds, and on May 17, 2004, the former Monroe School opened to the public as the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site.

Stop 10

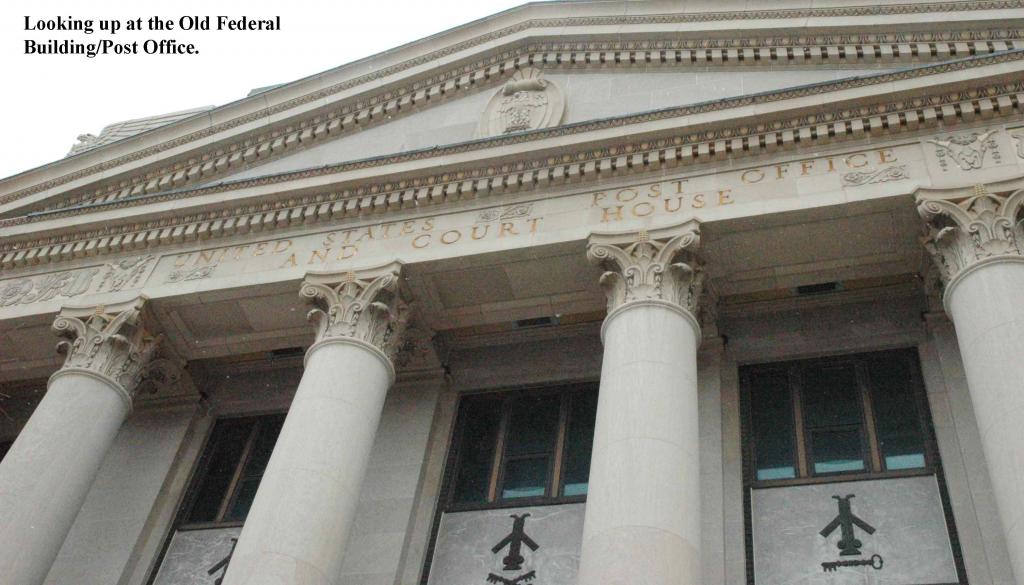

Old Federal Building

424 S Kansas Ave. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSOld Federal Building

424 S Kansas Ave. Topeka, KS

Topeka’s Old Federal Building housed a post office and U.S. district court, and was formally dedicated on August 30, 1934.

In June 1951, local attorneys John and Charles Scott and Charles Bledsoe, and other lawyers from the NAACP, representing 13 adult plaintiffs and 20 children, rose in the courtroom on the third floor to argue Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.

The three judge panel, bound by the “separate but equal” precedent established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), reluctantly sided with the Board of Education, clearing the way for an appeal before the U.S. Supreme Court. In a finding of fact, the district court voiced the opinion later adopted by the Supreme Court that legally sanctioned segregation hindered the mental and educational development of black children and deprived them of the benefits they would receive in racially integrated schools.

Stop 11

Our Lady of Guadalupe Church

201 NE Chandler St. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSOur Lady of Guadalupe Church

201 NE Chandler St. Topeka, KS

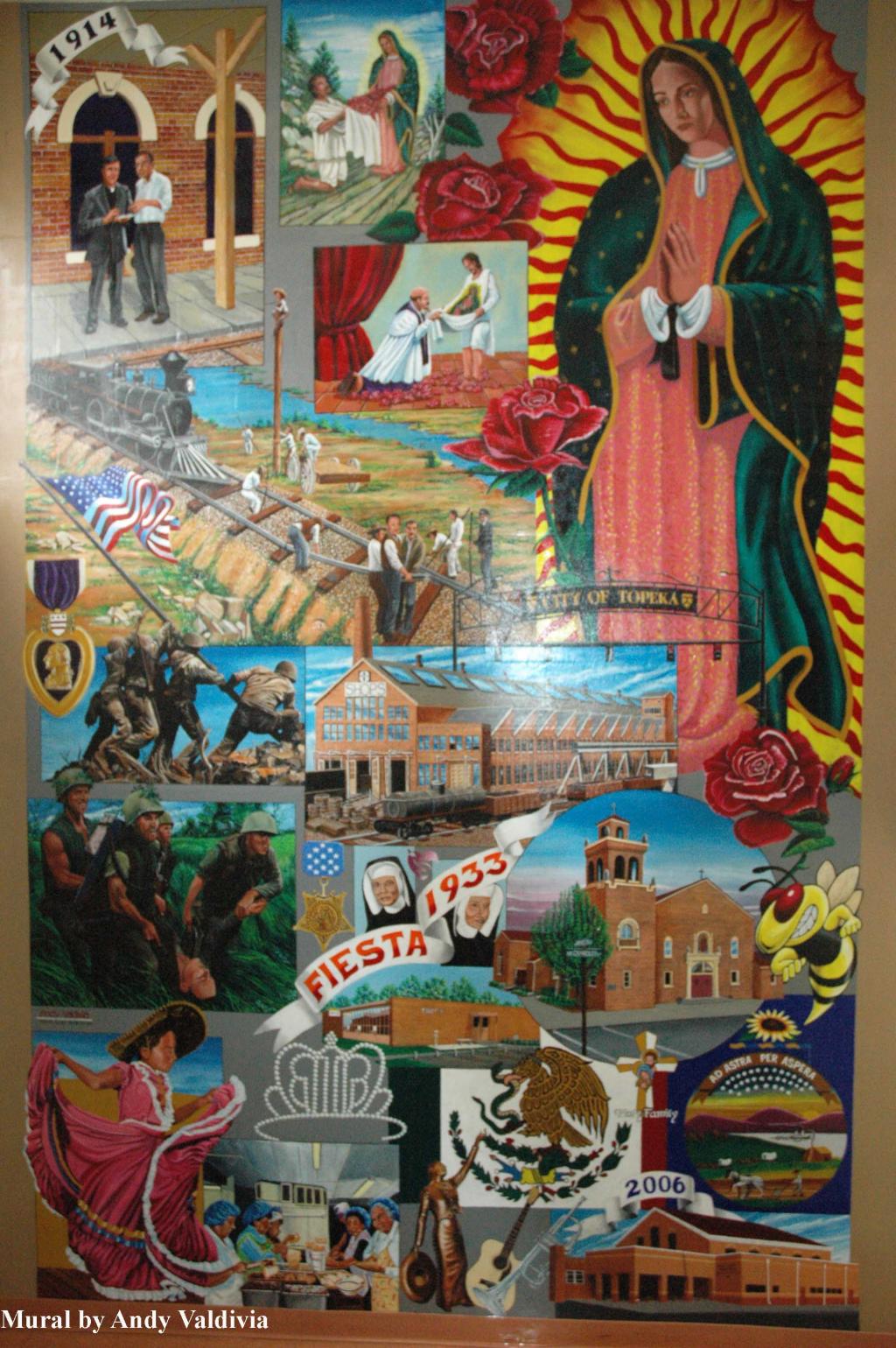

Nestled in the shadows of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad Shops, Our Lady of Guadalupe Church was constructed in 1914 and today is a pillar of Topeka’s Hispanic, Roman-Catholic community.

Our Lady of Guadalupe has held a Fiesta Mexicana, a celebration of Mexico’s culture, annually since 1933. By 1953, funds from the fiestas were used to expand the school to help house increasing student enrollment.

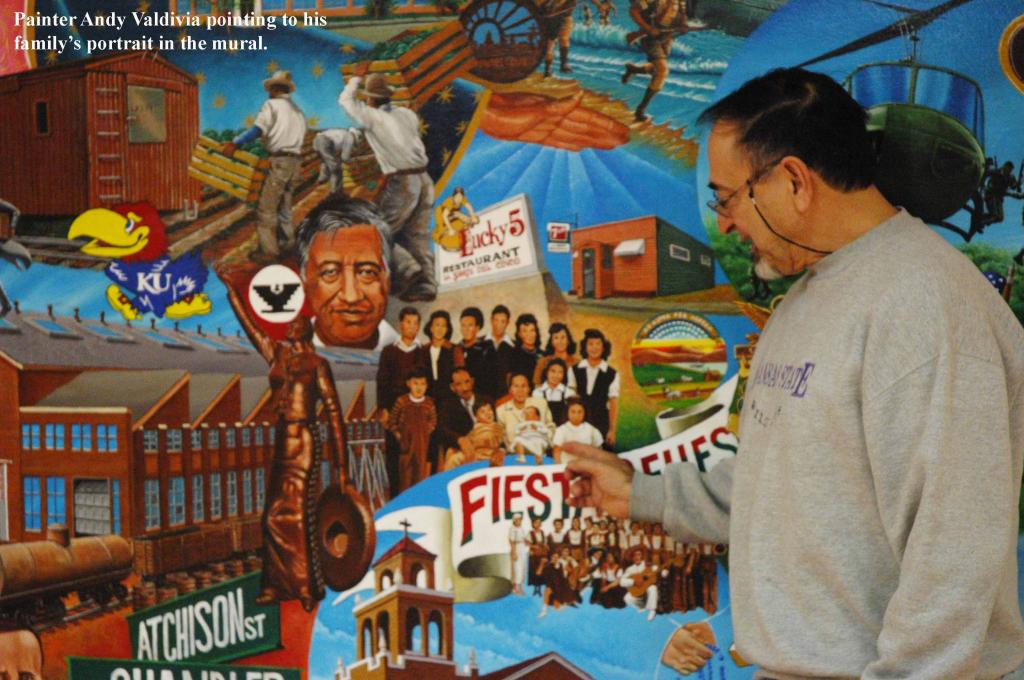

As an illustration of Our Lady of Guadalupe’s role in serving the needs of the local Hispanic community, local artist Andy Valdivia has vibrantly painted two murals located inside the church depicting the history of the parish.

Stop 12

Ritchie House

1116 SE Madison St. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSRitchie House

1116 SE Madison St. Topeka, KS

John and Mary Ritchie arrived in Topeka in 1855, drawn to the coming fight to ensure Kansas would become a free state. Family tradition states that this small two story stone house served as Ritchie’s Topeka residence from 1856 to 1869.

While most of those who had come to Kansas in the mid-1850s came seeking only a better life, others, like John Ritchie and John Brown, came itching for the fight to defeat slavery. John Ritchie rode with the Free State Militia and turned his property into a sanctuary for enslaved men, women, and children fleeing north.

Lawrence abolitionist Henry Hyatt recalled two trips to Topeka in a covered wagon in which two fugitive slaves were hiding. He left them at the Ritchie’s at midnight. It is believed that the Ritchies often hid fleeing enslaved people out in the thick underbrush and under rock outcroppings near their spring house, where Mary Ritchie would go to carrying a bucket of food without raising suspicion. In later years Ritchie claimed he had cost slaveholders $100,000 in human beings he helped smuggle to freedom.

Stop 13

St. Mark’s AME Church

801 NW Harrison St. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSSt. Mark’s AME Church

801 NW Harrison St. Topeka, KS

The first African American Methodist Episcopal Church was established in Topeka in 1878. St. Mark’s AME Church was built in 1920. Oliver Brown attended the church during the time of the Brown v. Board of Education case. In 1953, Brown became associate pastor of the church, serving until 1959. It was in this church that Rev. Brown first heard of the victory of the Supreme Court’s decision. Rev. Brown gave his only film television interview in the church’s sanctuary.

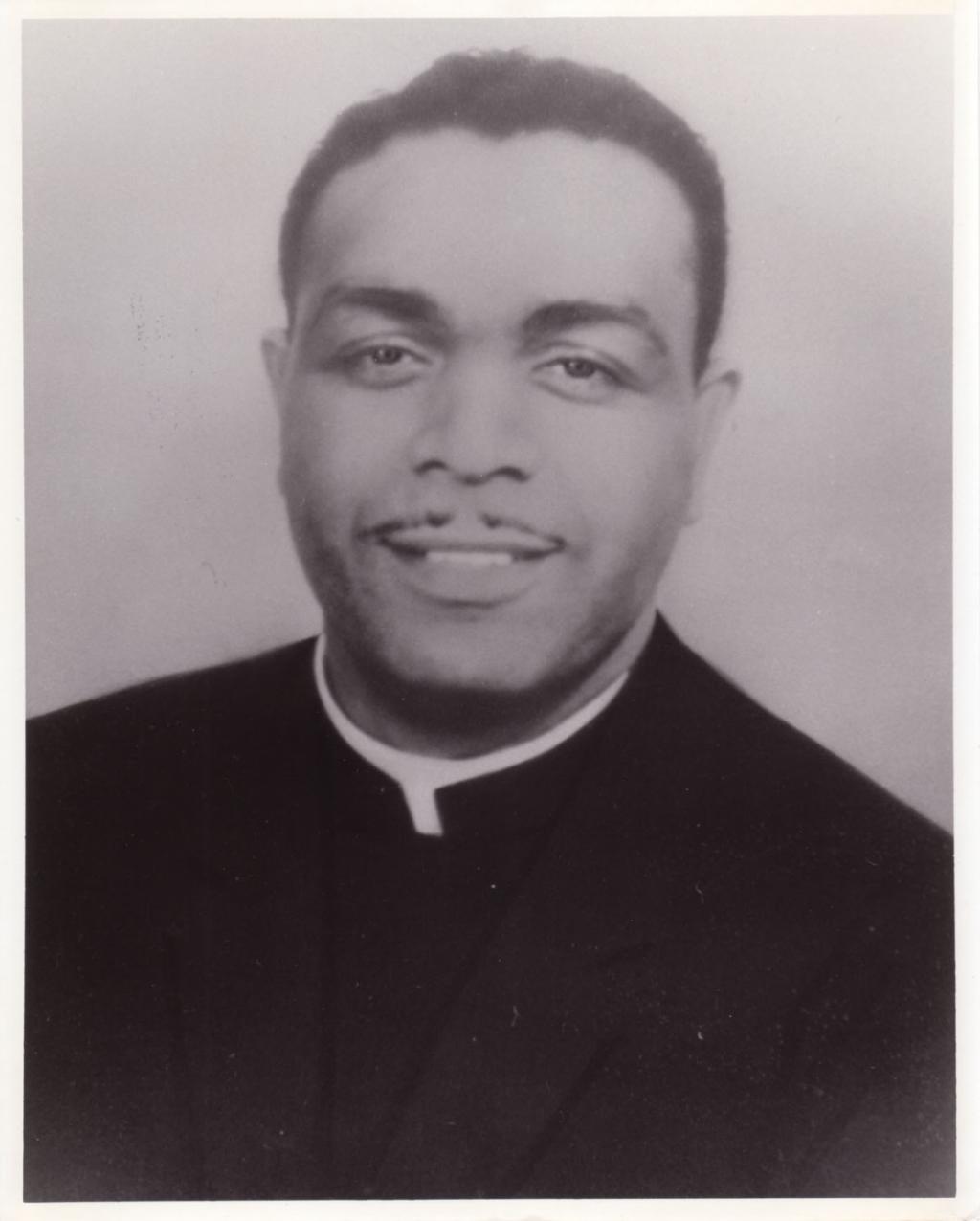

Many of the denomination’s clergy and lay people later became activists and participants in the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th century. Rosa Parks, who helped ignite the modern Civil Rights Movement when she refused to relinquish her seat to a white man aboard a city bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, remained a devout member of the AME Church throughout her life. Rev. Joseph A. DeLaine endured death threats and saw his home burned to the ground when he and other African Americans sought to secure equal educational opportunities for the black children in Clarendon County, South Carolina, during the Briggs v. Elliot case.

Equality and social activism have been cornerstones of the African American Methodist Episcopal Church since it was formed in 1787 by black congregants forced out of a Philadelphia church because of their race. In the 19th century, church leaders and members were often in the forefront of the antislavery movement. A number of black abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and Sojourner Truth, were members of the AME Church.

Stop 14

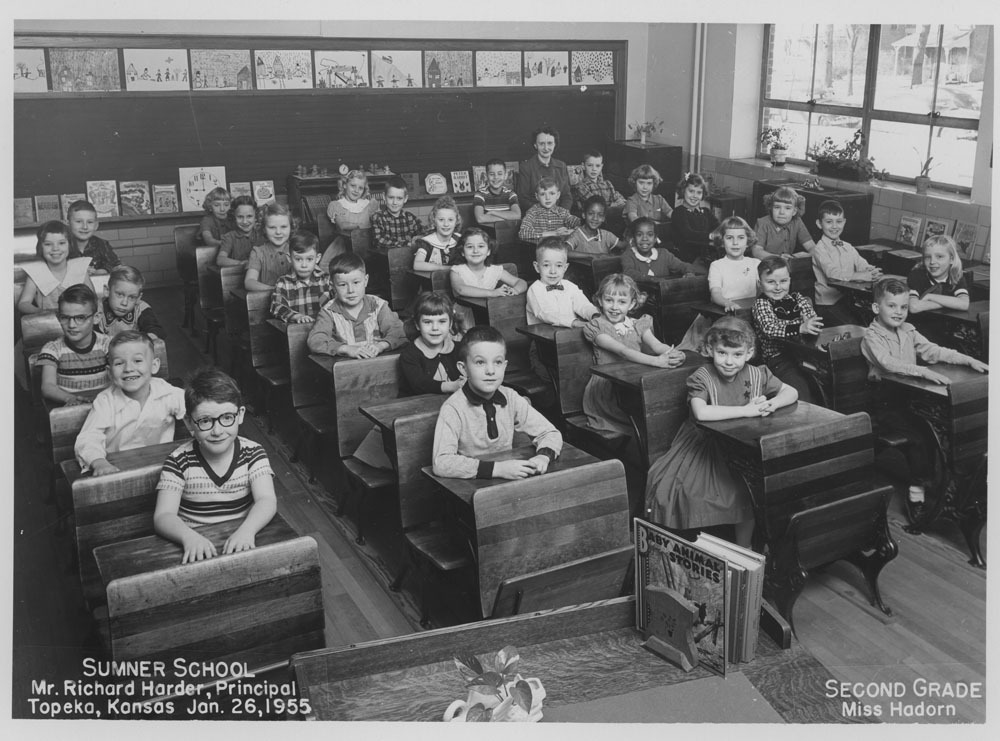

Sumner Elementary

330 SW Western Ave. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSSumner Elementary

330 SW Western Ave. Topeka, KS

Built in 1936, Sumner Elementary School helped launch the nation’s Civil Rights Movement, as one of the schools at the center of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education.

Sumner was one of 18 Topeka grade schools open only to white children. In the fall of 1950, Oliver Brown, under the watchful eyes of the NAACP’s attorneys, attempted to enroll his daughter Linda. Although the school was only 4 blocks from her home, Linda was turned away because of her race. Early the next year, Brown and twelve other parents representing 20 children filed a lawsuit demanding the immediate integration of Topeka’s elementary schools. In 1954 the Supreme Court ruled that segregated schools violated the rights of black children under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

In 1987, the National Park Service designated Sumner Elementary a National Historic Landmark, followed 5 years later by Monroe Elementary. When President George H. W. Bush signed legislation creating Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in 1992, Sumner Elementary was still serving Topeka’s black and white children. It closed its doors in 1996.

Stop 15

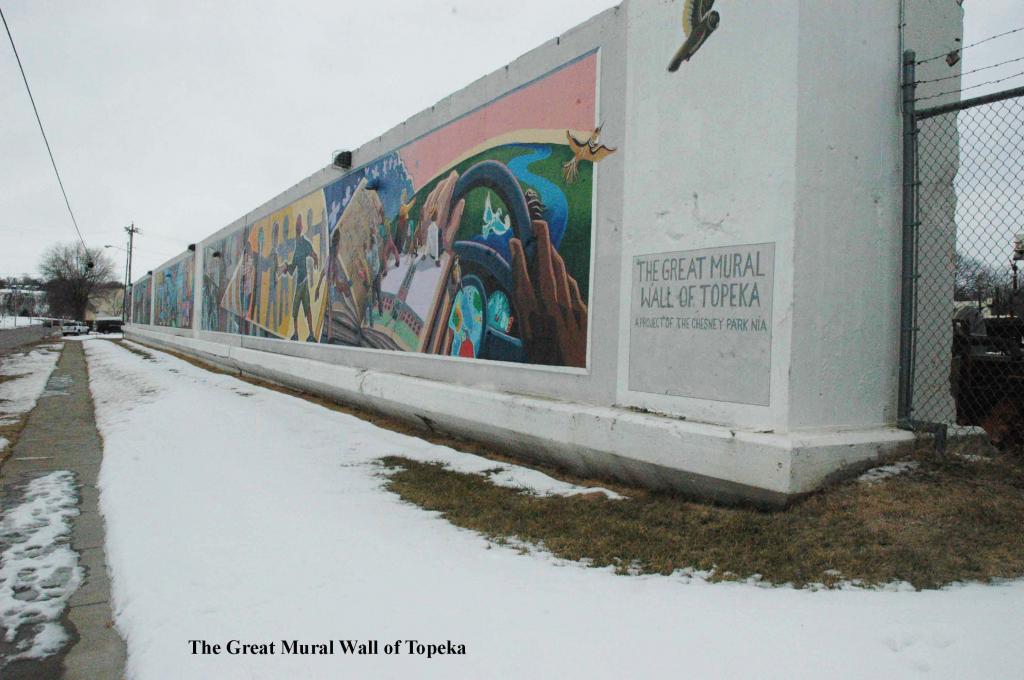

The Great Mural Wall of Topeka

1916 SW Fillmore St. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSThe Great Mural Wall of Topeka

1916 SW Fillmore St. Topeka, KS

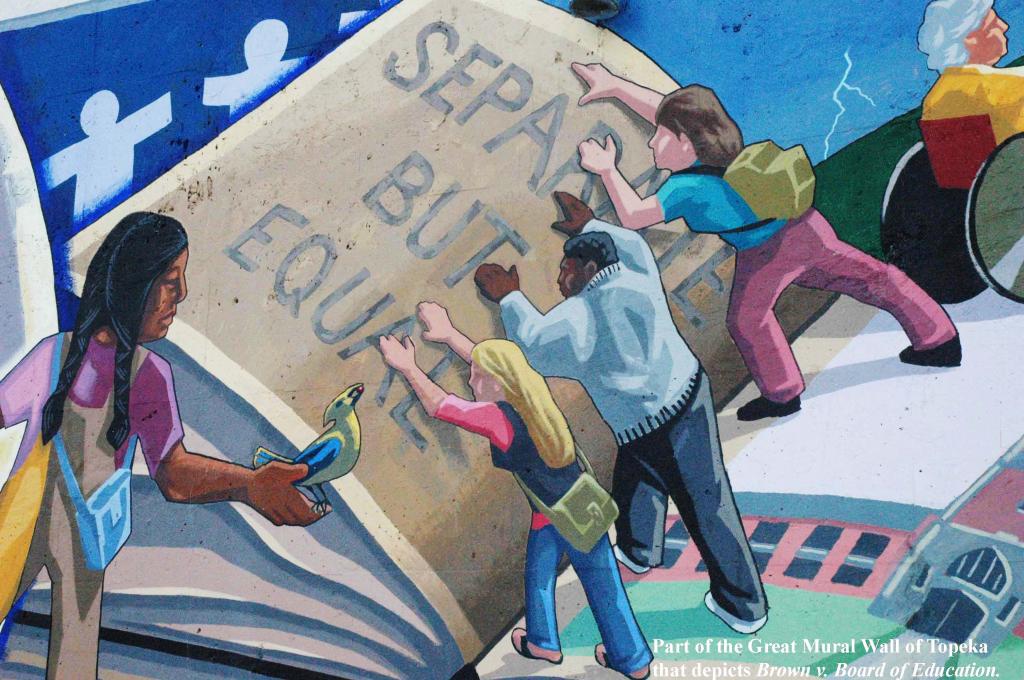

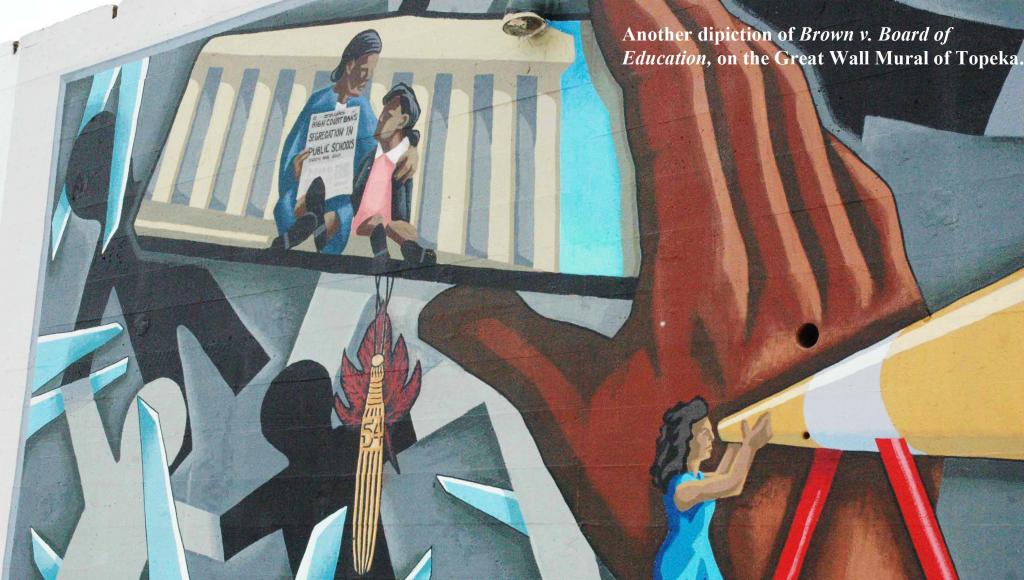

The Great Mural Wall of Topeka is located just west of the Kansas Expocenter at the intersection of 20th and Western.

The project was initiated by the Chesney Park Neighborhood Improvement Association. Painting on the mural began in 2006 on the sides of a large white building from 1931 that once housed a 10-million-gallon water reservoir for the city. The colorful mural now stretches across the entire length of an approximately 11-foot tall, 300-foot wall.

Scenes depict both Topeka’s history and a look into the future. Space for the mural was donated by the City of Topeka Water Division. The Great Mural Wall of Topeka honors the history, heritage, and people of the city.

Stop 16

Topeka Cemetery

1601 SE 10th Ave. Topeka, KS

DIRECTIONSTopeka Cemetery

1601 SE 10th Ave. Topeka, KS

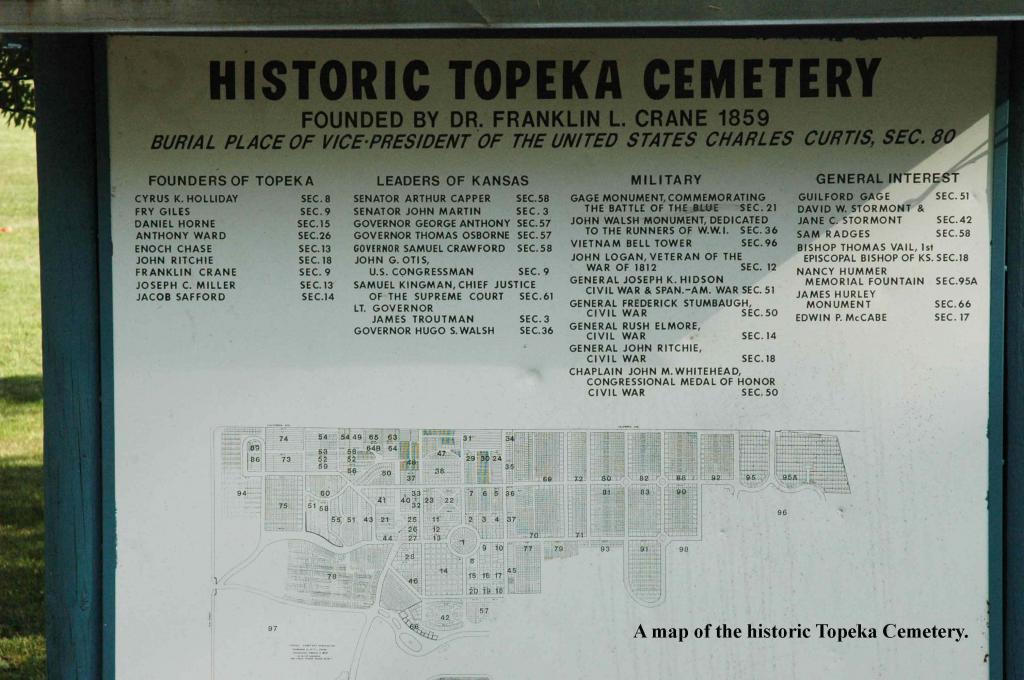

The Topeka Cemetery, established in 1859, is the oldest chartered burial ground in Kansas.

The cemetery is the resting place of many of Topeka’s most noted citizens, including Charles Curtis, the 31st Vice President of the United States, and Topeka founder, Cyrus K. Holliday. Five former Kansas governors, 17 Topeka mayors, and state auditor Edward Mcabe, the first African American to be elected to a state-wide office, are also buried here.

The cemetery is the resting place for about 250 veterans from every American conflict since the War of 1812. A monument erected in 1895 for the soldiers who died during the Battle of the Blue during the Civil War still stands. Mausoleum Row is a group of large hillside family monuments. It is on both the Kansas and National Register of Historic Places.